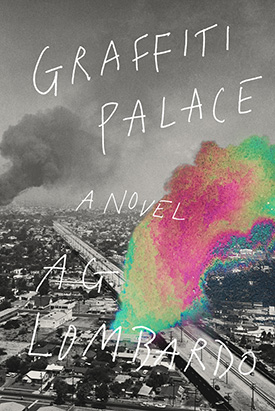

Graffiti Palace, A. G. Lombardo’s debut novel, is a contemporary reimagining of The Odyssey set during the 1965 Watts Riots. Los Angeles is scorching and Americo Monk, a street-haunting graffiti aficionado, is frantically trying to return home. Yet his trek is constantly diverted, and the journey that results is exhilarating and dangerous—at times paranormal—as he encounters various representatives of Los Angeles’s subcultures. Lombardo, a native Angeleno, joined author David Ulin for a conversation at Skylight Books to discuss how this book took form, how he drew from The Odyssey, and the intriguing pieces of the past he unearthed while writing the book.

David Ulin: Let’s start with this: how did this project first come to you? It’s one of these ideas, when you see it—it’s almost inevitable, but it’s also completely original. So how did you begin to develop this idea? Do we actually wanna tell people what the general idea is? It’s a sort of transposition of The Odyssey onto the Watts Riots, with that theme of returning home.

A. G. Lombardo: You know, like a lot of books, it’s rattling around in your creative juices for quite some time. There are mainly three themes to my book, I would say, which are graffiti, the Watts Riots, and The Odyssey. I was always fascinated with graffiti and, being a high school teacher, graffiti was always around the school. I was conscious of it, of course, being a native Angeleno—driving around, walking around—this graffiti everywhere. Some of my kids in high school would have notebooks filled with graffitis bombas, which are colorful sort of muraled graffiti.

Ulin: Their own drawings? Or drawings they were copying off of walls? Or both?

Lombardo: Both. They would take pictures and copy all of this graffiti, and some of it is great and artistic. Gradually, I found some essays and I started teaching some graffiti essays to my eleventh and twelfth graders. I personally was fascinated with graffiti as an underground language and as a voice of the dispossessed. And I would see, for instance, a billboard scrawled with graffiti, and I would think, Well, that’s great, they’re jamming the official consumer message. And then I would even see graffiti on the reverse of the billboard and I would think, Well, they’re making their own free billboard signs out of graffiti. So all this graffiti was rattling around my mind. And then I taught The Odyssey quite a few times to my twelfth graders because we did it as part of World Lit.

I personally was fascinated with graffiti as an underground language and as a voice of the dispossessed.

Ulin: Every road novel ever written grows out of The Odyssey.

Lombardo: Exactly. It’s Jack Kerouac. It’s the prototype. I had The Odyssey going for me. And, of course, all of us lit guys have read James Joyce’s Ulysses and to do an update of The Odyssey would be a great thing. So that was rattling around, too. And then I thought, Okay, I have LA, so what’s gonna happen in LA? And, of course, it’s not a big stretch to think about the Watts Riots, the Rodney King riots. I mean, it wasn’t that cut and dried, but that’s how it all sort of came together, I think.

Ulin: So this was your first novel. Were you writing all along or was this something that you wanted to do when you were teaching literature? Obviously you are deeply invested in writers and writing and books, but what was the thing that made the jump from reading and teaching into the territory of writing for yourself?

Lombardo: I wrote short stories when I was a kid. When I was a teenager, like a lot of adolescent boys, I discovered Edgar Allan Poe and H. P. Lovecraft, and I was heavily into horror films and fantasy and so forth. I was always writing.

Graffiti Palace was not my first attempt at a novel. I wrote a couple of novels but I wasn’t ready. They weren’t good. Then Graffiti Palace—it just sort of came to be. I started it ten or twelve years ago. I don’t wanna get too far up the track. I wrote the book and then I wrote a query letter, which is a one-page letter to interest publishers. I sent the letter to the New York publishing houses, which is really brilliant. So I was completely ignored of course. I moved on to other projects, notes for projects. I was teaching. I had a life. And then I thought, Well, I’ll try to get an agent. An agent is like a catch-22 thing. An agent isn’t interested unless you’re published, but you can’t get published unless you have an agent. I took the letter out again and I sent it to a few agents. A few months later I got an email from Bonnie Nadell, my agent. She said that she liked the first chapter and to send in the whole book. So that was a great moment for me. And then it’s also kind of funny how I worked on the ending of the book five times—I couldn’t write the ending. Every time I sent her an ending she said, “This is horrible. Do it again.”

Ulin: I’ve had that experience.

Lombardo: I didn’t know what to do. I sent number five in and I got an email from her, I don’t know, a week later, and she said, “Your ending was beautiful.” And that was that.

Ulin: Let’s talk a little about that. Writing a book like this, you are kind of using a template that we know. For me, one of the most interesting things about the book is that I have the sense of what’s going to happen—but I’m really curious about how it happens. I know it’s going to be a battle for Monk to get from where he is back home. What were the challenges for you in terms of writing a book that is original but is also kind of pulling on the movement of a well-known work?

Lombardo: I wasn’t really in full control of what I was doing. The book is 320 pages. When I sent it to Bonnie it was 460 pages. I had a lot of notes, and I’m not a stickler for plot. And remember, I’m just a guy writing by myself in my room. I had no expectations of it being published. I had no track record.

You’ve gotta write the kind of books you wish you could read.

Ulin: But that’s liberating in a way, right? You can do what you want to do.

Lombardo: That’s liberating. I can write without a net because I’m writing for myself. You’ve gotta write the kind of books you wish you could read.

Ulin: Exactly.

Lombardo: And I’m thinking, “If I don’t write this, who the hell’s gonna write this crazy book?” No, nobody. But to answer your question, David, what happened was I had some really key ideas of plotting it along with The Odyssey. Right? I had those iconic riffs I wanted to do, like the cyclops. You’ve gotta have the cyclops and Odysseus tied to the mast. You have to hit those high points. In between, though, I was just having fun having Monk going through LA, going through the riots. I guess the spirit of The Odyssey sort of took over and Monk encounters prophets and witches, voodoo practitioners, and a lot of even crazier things.

Also The Odyssey has Tiresias. Tiresias in The Odyssey was a blind prophet, and he gives Odysseus clues about how to continue with his quest. So I had this idea: this is 1965—there were just phone booths. I wanted Monk to have to go to these phone booths where he would get clues from a mysterious stranger named Tyre—short for Tiresias. And in the book, Tiresias takes on different shapes because in The Odyssey, Tiresias is a shapeshifter. So Monk sees him in a shoe shine stand as a shoe shine guy, and later in the book he sees him as a mumbling, blind, crazy street preacher. And then as a disembodied voice. I found a lot worked with The Odyssey, and when it didn’t, I was just having fun writing the story. I wasn’t chained to a plot.

Ulin: You’ve created this crazy landscape of Los Angeles, where the lid has just been blown off and everything is up in the air. I imagine from a writing point of view this gives you all kinds of freedom to go as weird as you want to go.

Lombardo: I consider Graffiti Palace an urban fantasy. It’s a bit of magical realism, a little bit of science fiction, and a lot of mainstream fiction, too. But the saving grace was that it was firmly anchored in reality, which was the Watts Riots. As I look at the book now, it was kind of a balancing act. The book is very wild but it never goes off into a dreamland or into something that’s not believable.

Ulin: That’s why you use historical figures, right? The traffic stop that triggers the riot is actually presented as a fictional scene, but as it happened with the real people and their real names. There are real historical figures that show up in the book: Elijah Muhammad as an example.

Lombardo: As I researched the book, I realized that there were all these wonderful real-life people and events and—in many cases—it was crazier than the stuff I was trying to write, so I had to incorporate it. For example, in my research, I found something called “the last American telephone booth,” which is a big thing on the internet-—you can Google it. Allegedly, the most remote telephone booth in America was out in Mojave in the middle of nowhere. Just imagine a dirt road going out into the wasteland and only a line of telephone poles connecting it. And in this real-life telephone booth, all the outsiders of the world would congregate. It was a mecca for outcasts and tramps and travelers and prophets. So people would go there and make phone calls to strangers and have these bizarre conversations. Or they would just wait there and the phone would ring. And of course the booth was completely covered in graffiti, so I had to work that into my book with Tiresias on the phone helping Monk in a few scenes.

Another great example is Gene Roddenberry. You guys know that Gene Roddenberry is the inventor of Star Trek, right? Captain Kirk, the Enterprise, all that great franchise stuff. During the Watts Riots, Gene Roddenberry was actually a cop. He was a sergeant, and he was Chief Parker’s right-hand man. Chief Parker was the police chief during the Watts Riots. Back then, there was no idea of community policing. It didn’t exist. The cops were more like enforcers. They just swarmed and knocked the hell out of you and put you in jail. That was the end of the story. And Roddenberry actually wrote the speeches for Parker and helped develop the containment policy to quell the Watts Riots. So I riff on that. To me it’s very funny because Roddenberry is like space patrol—he’s the master of outer space—and in my book the space he’s controlling is the actual grids of LA, the city, to contain the rebellion.

Ulin: It’s almost like the whole situation is so weird that all those elements fit perfectly. And then they have direct roots to the community, which is even better.

I like to write in the present tense because it’s visceral, it’s immediate, it’s happening now.

I have one more question for you. The thing that struck me as I was reading the first pages of the novel was the language. The language is electric and idiosyncratic—each sentence feels like it’s going for it. How did you develop that linguistic landscape?

Lombardo: Thank you, David. I like to write in the present tense because it’s visceral, it’s immediate, it’s happening now. I try to put the reader right in the middle of the action. Also—again, because I’m not a strong writer of plots—I think every paragraph has to be like a poem. I had one of the reviewers say that the language is like jazz, and that’s true. Language, to me, is something that you hear, and so a paragraph should be like a prose poem. If it doesn’t advance the plot, that’s okay. You’ll get there.

I’m also very influenced by film, by cinema. Every scene, I try to paint the picture—you’ve got to feel it and see it. I’m not so much worried about the meaning—that’s in there, too. But you have to trust your readers. Readers are intelligent. They’ll figure it out.

A. G. Lombardo is a native Angeleno who teaches at a Los Angeles public high school. Graffiti Palace is his debut novel.

David Ulin is the former book critic of the Los Angeles Times. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the author or editor of nine books, including Sidewalking, the novella Labyrinth, The Lost Art of Reading and the Library of America’s Writing Los Angeles, which won a California Book Award.