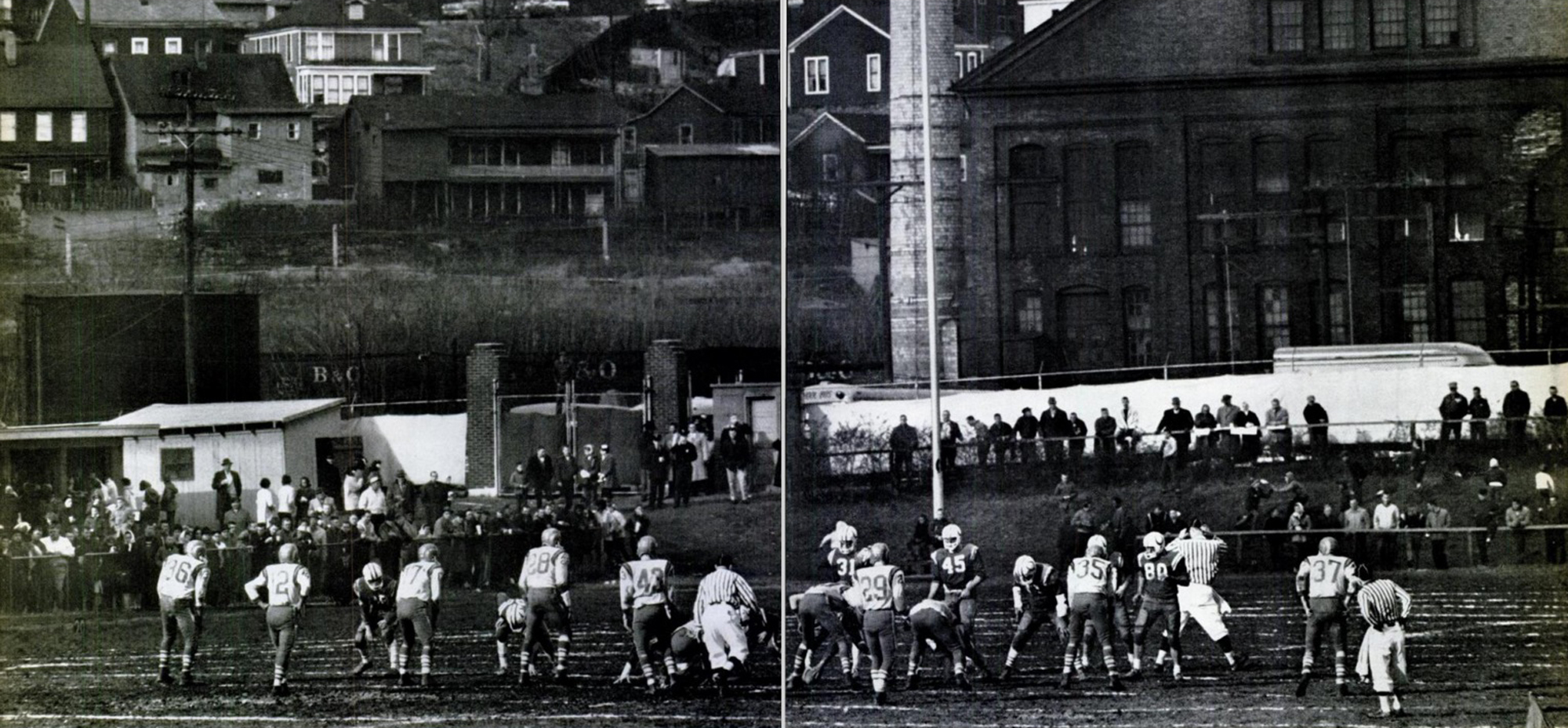

“Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio”

In the Shreve High football stadium,

I think of the Polacks nursing long beers in Tiltonsville,

And gray faces of Negroes in the blast furnace at Benwood,

And the ruptured night watchman of Wheeling Steel,

Dreaming of heroes.

All the proud fathers are ashamed to go home.

Their women cluck like starved pullets,

Dying for love.

Therefore,

Their sons grow suicidally beautiful

At the beginning of October,

And gallop terribly against each other’s bodies.

• • •

Much of the poetry of James Wright—a significant mid-twentieth century American poet—drifts perilously close, in hindsight, to sentimentality. This is the risk one takes in pursuit of generating some of the powerful emotions this particular poet is given to. Wright did, however, write at least two magisterial, indelibly beautiful poems, one of which, “Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry Ohio,” from his 1959 collection The Branch Will Not Break, is a truly great poem. The other, “A Blessing,” from the same volume, is splendid, if not quite of that stature. In both poems, Wright manages to bypass sentiment and, in doing so, he succeeds in achieving an emotional intensity seldom encountered in American or British poetry of that era.

The town of Martin’s Ferry, in eastern Ohio, separated from West Virginia and nearby Wheeling by the Ohio River, constitutes a narrow strip bordered by hills on the west and the river on its east. When Wright grew up there, the son of a die-worker, the town had a population of sixteen thousand. Coal mining and steel mills were the primary industries. It’s a far smaller place now.

The population would have been almost exclusively working-class, like Wright’s family. The males would have dropped out of school early and found work in the mills and mines; the females would have tended to get pregnant and marry young. There were, and remain, many equivalent places across the United States, if fewer, and now bleaker, than in the 1950s.

We are in a specific place, in a particular window of time, but it is everyplace, throughout time.

Wright’s poem is organized into twelve lines, divided into three short stanzas of irregular length, written in a loose free verse. The ostensible subject matter of the poem, very generally, concerns the pathos, born of limitation and disappointment, in a middle-western mill town circa 1950. The larger subject, underpinning the rest, is mortality. The poem develops through a series of assertions and observations. The tone or voice is neutral, dispassionate, in counterweight to the material, a technique which serves to complement the poignancy of the poem. Localness is enhanced by the use of place names—Shreve, Tiltonsville, Benwood, Wheeling. We are in a specific place, in a particular window of time, but it is everyplace, throughout time. The lines, and line breaks, are determined by units of meaning or by emphasis on particular words (“Therefore”) or phrases (“dying for love”). The diction is plain, but the success of the poem hinges on particular words, where they’re positioned, their weight and expressive range: “ruptured”—or combinations thereof: “starved pullets,” “suicidally beautiful,” “gallop terribly.”

73 words, perfectly judged.

August Kleinzahler was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1949. He is the author of eleven books of poems and a memoir, Cutty, One Rock. His collection The Strange Hours Travelers Keep was awarded the 2004 Griffin Poetry Prize, and Sleeping It Off in Rapid City won the 2008 National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. That same year he received a Lannan Literary Award. He lives in San Francisco.