In classical Chinese paintings, we routinely encounter a phenomenon that is strange and even shocking in terms of Western manners. Alongside the artist’s original painting, we find many later additions done by other hands: they are red stamps of different sizes, added by collectors—from ordinary collectors to emperors. Other additions are written in calligraphic handwriting on empty spaces on the scroll. By Western standards, this is a corruption of art. Just imagine what it would be like to add a stamp or verses of a poem to a Rembrandt drawing in a museum. You could get shot for such an act. And even if the drawing was privately owned, such an act would be condemned as immoral and mortally damaging to both the artistic and market value of the piece.

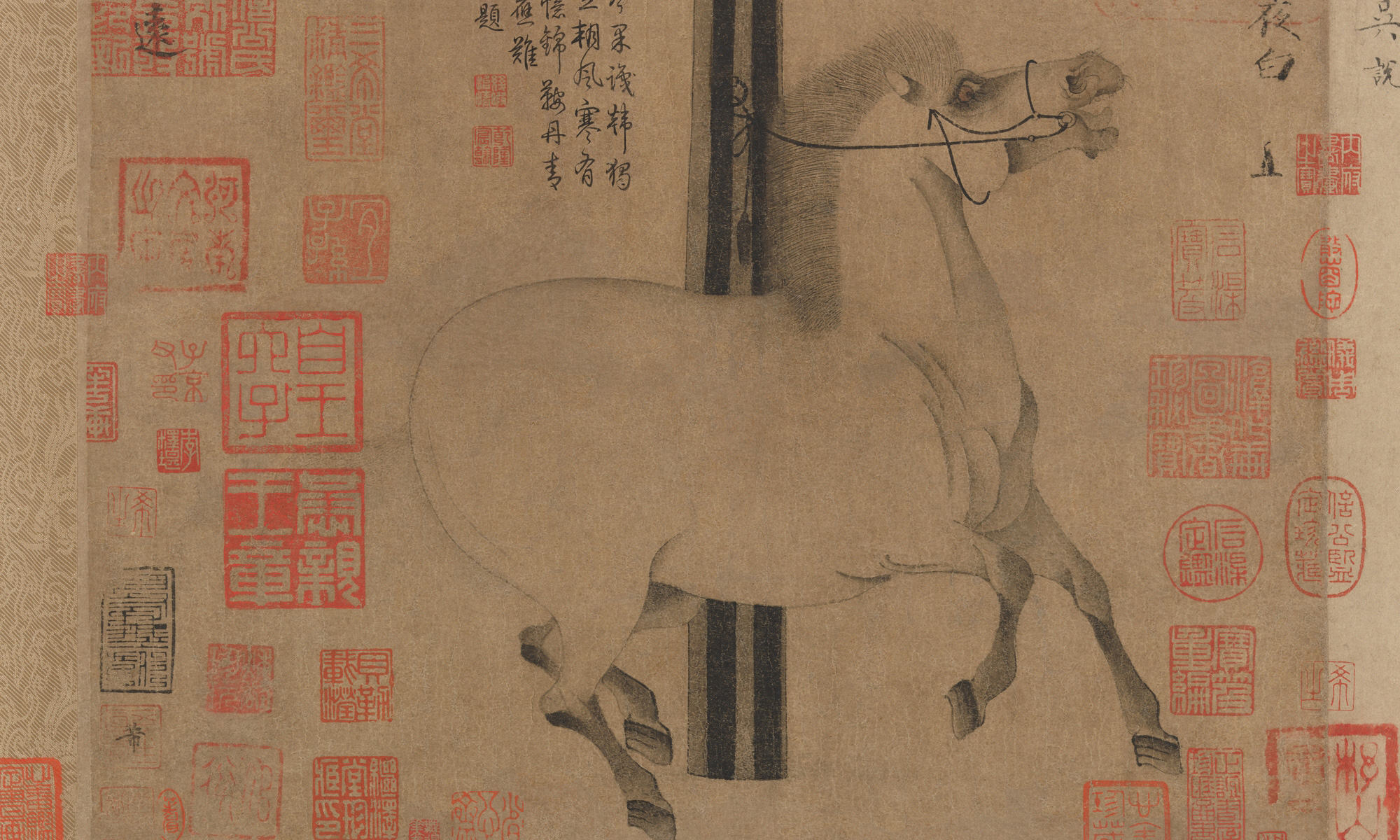

However, the Chinese do just that. In this famous painting by Han Gan from about 750 CE, which belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, dozens of inscriptions and additions appear alongside the horse. There is no sense that those additions ruin the original or weigh on it. On the contrary, they bring it back to life, over and over again, over hundreds of years. In fact, not only do they revive the horse, but they also stimulate each other. Why? Because the seals and calligraphies themselves are small works of art.

Chinese art scholarship has told us that there are enormous temporal gaps between these additions. For example, the large square seal on the upper left is from the ninth century, while the calligraphy above it is from the seventeenth. Still, they live with each other —and with the horse—in peace and harmony. There is a feeling that as long as there is room it will be possible to add more, and the horse will continue to hang there, surrounded by additions but not destroyed by them, forever looking at the faded big stamp in front of his eyes, almost stamping the little stamp under his hoof.

No one would dream of putting a stamp on the horse’s body, because it would be in bad taste; nor would one dream of stamping a foreign color—say, green. Everyone wants to continue the conversation with the horse and the other seals; to fit into the traffic, not to honk, and certainly not to run over the horse.

Anyone who writes poetry gallops alongside the horse. There is no point in trying to eject anyone from the back of the horse, because the saddle is always empty.

Anyone who writes poetry gallops alongside the horse. There is no point in trying to eject anyone from the back of the horse, because the saddle is always empty. Gary Hotham, the great American haiku poet whom I had the privilege to translate into Hebrew, jokingly said once that he works on the Great American Haiku. Novelists sometimes have that pretention—to ride the horse alone, to write about “everything,” to say the final word. Poetry, not just haiku, knows too well we can only leave a mark on the margins. There is no point in hesitating to adding a verse there—fortunately, that is the only available place for us all.

Dror Burstein was born in 1970 in Netanya, Israel, and lives in Tel Aviv. A novelist, poet, and translator, he is the author of fourteen books, including the novels Kin and Netanya. He has been awarded the Jerusalem Prize for Literature; the Ministry of Science and Culture Prize for Poetry; the Bernstein Prize for his debut novel, Avner Brenner; the Prime Minister’s Prize; and the Goldberg Prize for his 2014 novel, Sun’s Sister. His new novel, Muck will be published