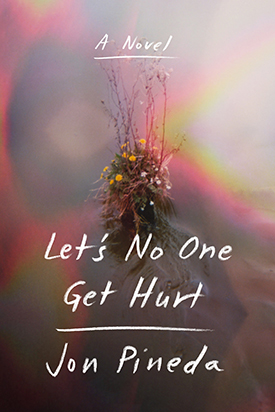

Jon Pineda’s Let’s No One Get Hurt is an “achingly beautiful” coming-of-age story following a teenage girl scavenging and squatting on the fringe of the American South (Lauren Groff). Pineda’s richly textured depiction of place was inspired in part by his own childhood—here, he reveals the formative memories of the family farm that later inspired his novel.

When I was a boy, I took a trip with my mother to visit the farm where she’d grown up. It was just the two of us. We’d left the rest of our family at home. I’d been to this farm countless times before—knew, in some ways, what to expect. For instance, because it was warm and had been for some time, I knew the figs would be nearly ready to drop from the squat trees that lined the old house, the one that rose, sun-bleached and splintered, in the middle of the tall cornfield. No one lived in the house anymore because it was starting to fall in on itself. Our uncle had a trailer parked in front of the house, the trailer itself just a notch above disrepair, but the two structures together seemed seamless to me, inseparable as places where people lived and continued to do so in increments. All the tethered past appeared to fall apart willfully.

In front of the trailer was a well with a hand pump, and I had already been shown times before how to scoop up some gathered rainwater in a dented tin cup and, while working the handle, pour the warm water into the metal throat. What eventually gushed forth was the coldest water I would ever taste in my life. There was also a trace of mineral and metal, the brisk tang of the earth. Though my father grew up near rice fields in the Philippines, thousands of miles from this one spot, I felt somewhat connected to his childhood home then, too, just as I felt connected to my mother’s. It was as if the mystery of where this water had been pulled from could have been linked to anywhere, which made it pliable in my young mind. I have never forgotten the taste of that water, nor the longing it left inside me.

I have never forgotten the taste of that water, nor the longing it left inside me.

The farm butted up against a wide river my mother and I had crossed by bridge in our yellow Gran Torino with faux wood paneling. The station wagon rocked like a boat for most of the drive. I’m sure it had something to do with its terrible shocks, but I didn’t care. At times, we were adrift. I remember listening to my mother talk about her childhood, the poverty of it, with a smile on her face. She, of course, never saw it as difficult or hardscrabble, and at the time, while I was held by her stories, I didn’t see it as that either. It was just living. And because all around us it was August, the air that pushed its way through the open windows was balmy, and when we slowed down in spots to pass tractors and other farm equipment out on the main road, I could almost fall asleep in that air, in that way an atmosphere takes hold and finds the crevices of our attention and wedges itself deep into the imagination.

It was during this same trip that we took my uncle to buy beer at a little country store where they also sold peach-flavored hard candy that was scooped out of glass jars behind the counter, weighed, and slid into little brown paper bags. Over near the beer were jars of pigs’ feet floating in pink brine. The elderly woman who ran the store remembered my mother from when she was a girl. My uncle, who routinely visited on his bicycle, stood off to the side and regarded the wood-planked floor. He always wore the same thing: drab olive-green pants and a matching button-up work shirt. If I squinted, he looked as though he could have been his younger self, an army soldier in World War II, but one who had gone on to simply age in the same uniform they had issued him.

My uncle’s life revolved around farming and sometimes drinking with a friend, and so after my mother bought him his beer, we drove him down an unpaved road, through a cluster of trees that opened up onto the river. At the end of the road was a boathouse. There were rusted gas station signs that had been hammered up to cover holes in the walls. We parked beside the boathouse, and an elderly black man, dressed in the same olive-colored clothing as my uncle, stepped out and waved. His shirt was covered in sweat. Ours were covered in sweat, too. My uncle greeted the man with a handshake and then a cold bottled beer he had pulled from the crumpled brown sack holding the rest. I dug in my pockets for the little bag of candy I had been given. As I studied the boathouse, I tasted peaches. The two men settled into chairs under the overhang, the mouth of the brown sack open between them.

“Are you good?” my mother said to her brother.

“Yeah,” my uncle said. “You can go on. We’re good.”

You can’t go back to this place, because it was sold off long ago. There are condos there now.

From that moment on, the boathouse stayed inside me, as did the river. As did the image of these grown men drinking and sitting out near it, trading stories and making each other laugh. You can’t go back to this place, because it was sold off long ago. There are condos there now. And you can’t drive out to the family farm and see the house, because it has since fallen in on itself. No one uses the pump anymore to draw that coldest of water up from the darkness. And every now and then I find myself wondering about those figs I knew were waiting for me. Before we left to buy beer for my uncle, I had picked a bruised fig up from off the ground. I found a side of it had already split open, and within its core a hornet was emerging from strings of sticky pearls. I have this image of my younger self in that frozen, sweltering moment, before the small tragedies that come from living a life would try to start stacking up. I shook the fig, not to free the hornet, but to taste the sting of such sweetness.

Jon Pineda is a poet, memoirist, and novelist living in Virginia. His work has appeared in Poetry Northwest, Literary Review, Asian Pacific American Journal, and elsewhere. His memoir, Sleep in Me, was a 2010 Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and his novel Apology was the winner of the 2013 Milkweed National Fiction Prize. The author of three poetry collections, he teaches in the MFA program at Queens University of Charlotte and is a member of the creative writing faculty of University of Mary Washington.