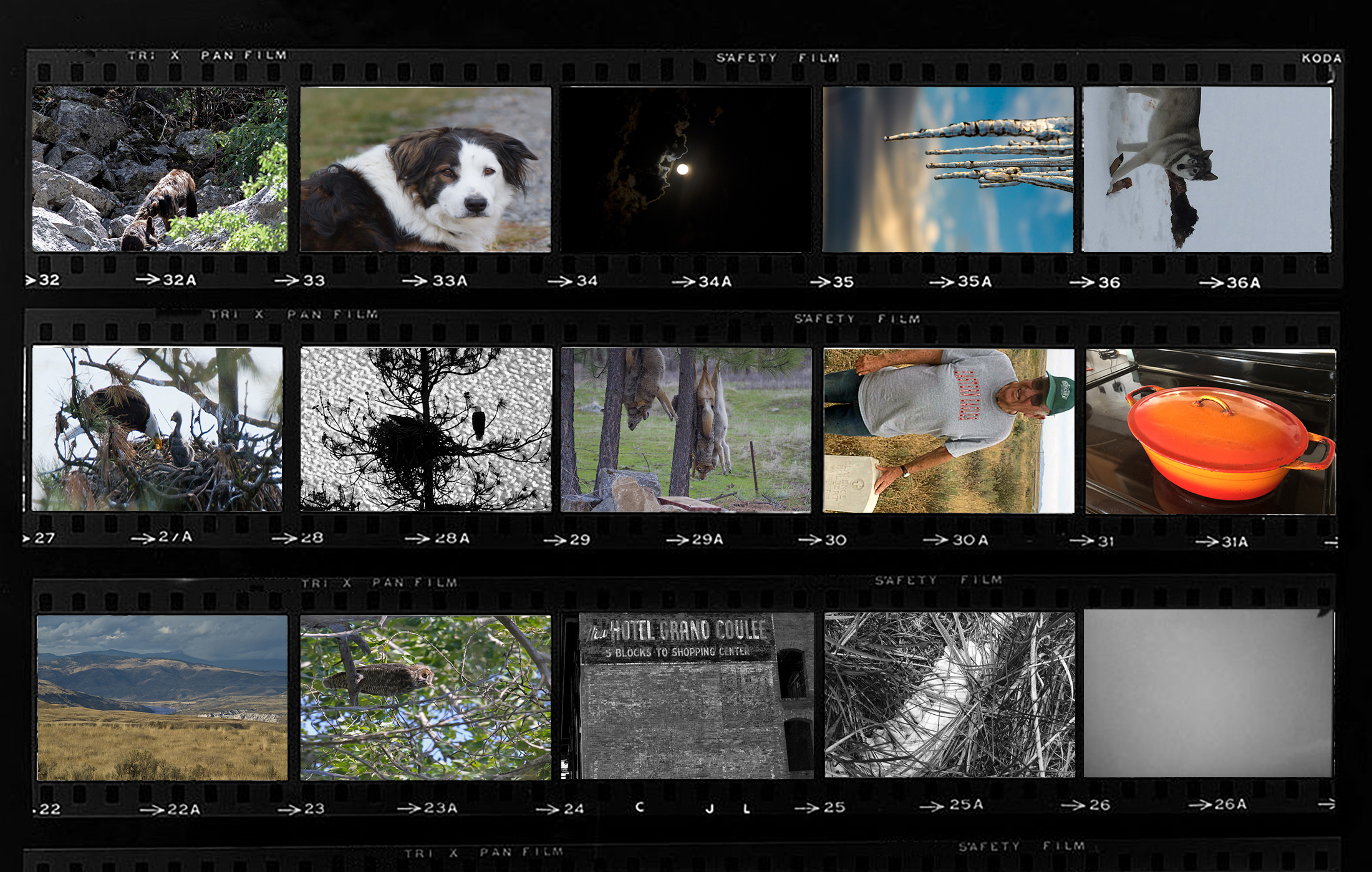

Developing Stories, a new series from Work in Progress, invites authors to take photos capturing the world around them—a reading, a walk in the woods, a tour of their hometown. This week we glimpse the rugged life of Bruce Holbert, author of the forthcoming book Whiskey. Holbert captures the harsh terrain, piercing natural beauty, ferocious wildlife, and local histories that pulse through Washington State, revealing the brilliance of sights both immediately grand and seemingly trivial.

I discovered this deer jaw on my property this spring. With tough weather or plagues like Blue Tongue, it’s not unusual for something to die on the property. The dog finds it first, and then I get whiff of it and have to bury a deer. Except it’s winter. The ground is harder than concrete and I’d have to get three feet deep to keep the dogs from digging the body up and hauling it around like a trophy.

So in the garage the kids had an old sled they didn’t have much use for. I got the sled and some rope and tied the deer to the sled. The dog, of course, watched all this ruefully. He followed as I dragged the sled to a steep grade leading to the river and shoved it off. I did not expect the deer to stay on far, but I hoped far enough. The deer managed admirably. Ten foot skips, somersaults, rollovers, and a head on with a tree three hundred feet below and it still remained aboard. I looked at the dog and he at me.

“Did you think it would go like that?” I asked.

The dog looked over the bluff as if he had not heard me, perhaps contemplating the unfairness of the world in which he resides. Deer now rode sleds.

What dog religion this would inspire, I still wonder.

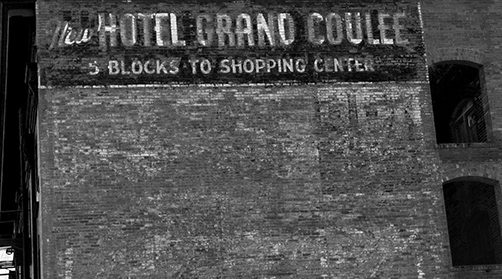

An old building in Spokane that was once a hotel named for The Grand Coulee. It’s about the right color, orange and yellow brick. The place was once a hotel, but now it is tiny apartments and served as low-cost housing. The bottom floor is storefronts, craft shops that have paved the way for urban renewal in the city, and I wonder how long before the apartments are rearranged and sold as condominiums. The folks there now will hope the developers oust them in summer when the park grass is soft.

Owls are tough on pets. We’ve lost to them three cats and the neighbors a Chihuahua. A year ago we had a terrible windstorm that blew trees down all over the county. One the storm toppled a mile from us was a hollowed out dead pine, surrounded by owl pellets. Inside were two hundred pet collars.

This is God’s Country, we say, if He has a sense of humor. It is harsh and hot and rocky in the summer, and frozen and slick and drifty in winter, but with that green and blue river, bruised and brooding under clouds and shining on a clear day, well, it’s a kind of pretty. And there is the sound. The river just saying itself into a river over and over.

Valentine’s Special

Crazy Eddie’s Tavern

Starters

Blanton’s Bourbon straight up to start. Then another with a domestic beer—nothing lite or micro, that dog won’t hunt here. Appetizers: fried chicken parts (see later on) and half a homemade dill pickle or, if you’re feeling froggy, some Chinese pork and seeds or wontons from the restaurant next door. They’re not on the menu but Eddie will make a call and the old fellow running the place will leg them up the street to you. Don’t be afraid to tip him. He gives the money to the girls in back.

Main course: Crazy Eddie’s homemade chicken and noodles

(Not a soup, not quite the consistency of a stroganoff, somewhere between.) Contains onions, salt, pepper, Old Bay, boullion, flour (for bulk), a little garlic (a little now, it’s not Italian), some onion salt, celery salt, a pinch of red pepper, a handful of frozen peas, carrots, and beans. Some chopped celery, half can of cream of chicken soup, big scoop of sour cream. No cheese, damn it; that’s a casserole. Seven chickens (everything but the entrails, fry them up in flour and grease and serve as the appetizer with tartar): cut them into pieces no longer or wider than your pinky finger—they’re going to get shredded in the cooking. Put it on to simmer and cook for a couple of days. Add a few cigarette ashes, as Eddie smokes after hours when he prepares this meal.

Make homemade noodles (the kind you roll out on a cutting board) at least half an inch wide (the width of Eddie’s index finger) and a quarter inch thick and six inches long at least, enough for a pot with seven chickens, I guess. Err on the side of too many—you can always feed it to the dog that lives in the place. Add the noodles about a day and a half after the rest has been cooking.

Finally, add a whole picnic ham, then take it out thirty seconds later. Eddie makes sandwiches out of it, but swears the noodles and the ham are better for their brief encounter.

Serve it for dinner that night on a plain white tavern plate with a fork you bought in a thrift shop. If you need a spoon, the thing is too damned watery, add flour. Add a peach when they come on, or apples—they’re easy to get around here. Get them from Dorothy Holbert’s house. She’s got apricots and plums, too, and you know they’re fresh then. The damned Safeway will sell you something from last year they got in Tijuana for Christ’s sake.

More beer. More bourbon.

Dessert

Forget it. You eat this, you’re going to need to hike five miles uphill just to get your cholesterol squared away.

P.S. Just kidding about the Blanton’s. Who the hell can afford that? Only folks without enough troubles to justify drinking. Just make sure it’s bourbon from Kentucky. No blends. No Jack Daniel’s. It’s from Tennessee and sour mash and will leave you with the whiskey shits, a crime against humanity for them drinking the real thing. And no ice. The beer is cold, that’s enough, even on a hot day.

Bring your own flowers, Eddie doesn’t get on with the florist.

My dad at the gravestone of his father, who was killed by my dad’s grandfather. It’s a strange place. For many years no one spoke of the murder. My grandmother was a stoic pioneer, teaching school at several homes during winter, hauling her horse-drawn sled to the neighbors’, where they would remain a week to finish their lessons.

My dad only discovered the stone a few years ago. He said he’d just never been inclined to look before. He is eighty two. I’m glad he finally got inclined. And out there, he and I together decided to add a marker for my Grandma, whose ashes we spread over the old ranch many years before.

He himself will be laid to rest at the Spring Canyon Cemetery nearer town next to his wife and my stepmother. She taught school many years, and inscribed in her half of the stone is “beloved teacher.” On my father’s, “beloved fisherman.”

Several dead coyotes tied to a tree on the reservation. The state provides a bounty for each hide.

When my dad was a boy on the ranch, the coyotes used to try and ambush his dog. Several would lie in the brush while one would show itself and feign distress. My dad always said of coyotes, “If you can’t see them, that’s how you know they’re there.”

Coyotes are the chief character in the mythologies of the tribes I grew up around. Coyote is an audacious fool. He created the Columbia River and put waterfalls in the tributaries that served villages that wouldn’t give him a maiden for his efforts. Once, raccoons waited for him to go to sleep, then cut out his anus and cooked it. When he awoke, they fed it to him. The gooey stuff in children’s eyes when they wake is Coyote’s semen, left to cloud their vision at night while he copulates.

Coyote dies occasionally as well, and remains dead until one of the other animals jumps over his body three times. My stepbrother was nicknamed Coyote by my father for good reason. He has no Animal Person to step over him three times if he falls, though he lives like he does.

This eagle pair nested in a tree a few hundred feet below our house on the river. We watched them crash into each other mating, then construct their enormous nest, then alternate brooding over the egg until their chick hatched. Eagle chicks look like chubby dinosaurs for a long time. We watched the eagles all summer. The chick grew bolder and tried to fly. At first, the parents would swoop back to the nest when the eaglet teetered toward the rim, until finally he had acquired enough feathers to make flight manageable. He was not very good at first, which was comical to me, but the parents scolded him back to the nest. Eventually, he took to flying on his own, enjoying windy days, especially, when eagles don’t have to wear themselves out with flight; they just soar the currents.

I know you could see this on National Geographic television or see the eagles at least in an aviary and get the gist. But I saw it from my deck. I heard it mornings before work. I can’t tell you the difference, but I can say there is one. Maybe it’s too wide a leap to explain to others.

A few miles from our house, a wolf attempts to take a deer it’s killed to less exposed country. “Life is the flower that feeds on flesh,” Cormac McCarthy once wrote. Damned if I can put it better.

You think it’s pretty; I think it’s 3 degrees.

Now how do you get to that bridge?

Tank, the dog, who chases deer and wild turkeys until they chase him; then he suddenly wants to be an indoor dog.

There is a story that dogs used to talk to man, but the dogs revealed the secrets of the old woman in the moon, so she put moon dust in their mouths so they could no longer speak. Every night they howl and cry to the old woman, pleading for her to return their voices.

Bruce Holbert is a graduate of the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His work has appeared in The Iowa Review, Hotel Amerika, Other Voices, The Antioch Review, Crab Creek Review, and The New York Times. He grew up on the Columbia River and in the shadow of the Grand Coulee Dam. His great-grandfather was an Indian scout and among the first settlers of the Grand Coulee. Holbert is the author of The Hour of Lead, winner of the Washington State Book Award, and Lonesome Animals. His new novel Whiskey is out March 13.