We’re pleased to present a new poem from Gjertrud Schnackenberg, “Afghan Girl.” Schnackenberg sat down with poet Susan Gillis (The Rapids, 2013) and professor Gregory Fried to discuss the process of writing the poem, the inspiration from Steve McCurry’s iconic war photograph, and the intersections between the political and the religious.

Gjertrud Schnackenberg

“Afghan Girl”

Sharbat Gula

Steve McCurry, 1984

As if broken in upon

By the spirit of God,

She turns to look.

Daughter,

From a psalm of King David.

Happened upon

In a refugee tent

In Nasir Bagh,

In a temporary encampment

In the North-West Frontier Province

Of western Pakistan,

During a breathing spell in war.

A lost flight out of Egypt

Brought to a halt in 1984

At the edge of Peshawar.

A girl the color

Of sawdust shavings

From the cedars of Lebanon,

And a glance, inadvertently granted:

An onslaught of green

In Kodachrome 64.

♦

A glance King David could have seen,

Looking up “at the turn

Of the year, the time when kings

Had gone forth to battle”—

As if, looking up, he had found

The child of a slain Philistine,

Standing no further from him

Than the length of an arrow.

Standing her ground.

♦

Light green sea glass

Washed up on a shore

In Canaan,

The music of Psalm 33,

Unfaded: He hath

Gathered the waters of the sea

Into jars. He layeth up

The ocean depths

In storehouses—

Found, hoarded, traded

Into landlocked Afghanistan

From the treasury of David.

♦

The photographer said

It was a kind of “blue-green-gray”—

The gray tint

Fugitive, tent-lit,

An illusory pane of glass, flash-seen

Then vanishing

Among the steep, dark-green

Quarry walls of a refugee tent.

A shade of gray evolved

As camouflage, far west

Of Nasir Bagh, among the gray peaks

Guarding Persepolis:

A clutch of Persian Eagle eggs

Wind-accosted in a nest

Built on a precipice.

♦

In a glance,

An overhanging sense

Of Pashtun magnificence,

The unalterable code

Of asylum for the enemy

And hospitality for the stranger

Without expectation

Of return, however destitute

The circumstance.

A glance that is at once hostage

And its own

Immeasurable ransom, bestowed

In the poverty of a camp

By a twelve-year-old

With a grave, Islamic courtesy.

Translucent planes

Of yellow-lit

Blue-gray-green—

A roughed-out chunk

Of aquamarine,

Unpolished, uncut,

Its presence first hinted at

By a visible plane

Of microcrystalline,

Recently clawed

From the gem-bearing pegmatite

In the cliffs of Nuristan,

As if her people had opened a vein

In a quarry they dug

In the kingdom of God.

The gem, unloosened

From the granite’s grip

With delicate hand-tools,

Is washed repeatedly

Of its enclosing grit and clay,

With expert care.

Though nothing can wash away

Its blue-gray-green.

Because Allah has stored it there.

♦

In Sura 3:44

Of the noble Qur’an

The archangels cast lots

To determine which of them

Would be entitled to care for her.

The child, Maryam.

Found here at the moment

An angel has offered her water

To sip from his palm.

Green marble chipped

From the quarries

Of Lashkar Gah

And set into mortar

In the turquoise glaze

Of the mosque at Kandahar

Where a glimpse before purdah

Tessellates in the walls

And startles the angels of Allah,

His Messengers disarmed

By a suddenly broken law

In the mosaic.

A gaze older than Islam,

More archaic

Than the precepts it violates.

♦

Wild olive branch,

Carved in the idol workshop

Of Azar.

Even Ibrahim was disarmed.

Even he, breaking the idols,

Kept this one unharmed.

♦

A Hadith tells

Of the archangel Gabriel’s

Refusal to set foot

Into the Prophet’s tent,

Because the angel was certain

That, though unbeknownst

To Mohammed, an image

Was housed within—

Perhaps a picture

Woven in a threadbare cushion

Or faded in a curtain

Long unnoticed, half forgotten,

Among the Prophet’s

Scant possessions.

But so accursed are pictures

In the Qur’an that even

Mohammed—blameless,

Awaiting the angel’s dictation—

Even he was left to wait,

Unvisited, while Gabriel

Lingered, unable to enter

Because no image that is “made

As an act of creation,”

May be displayed

Or stored out of sight,

Beheld, or kept unseen,

Either secretly or unawares—

On the Internet, a true believer

Inquires: is all photography

Against religious law?

The rulings of the imams disagree.

There is no final word—

She turns, in Kodachrome’s eternity,

As if she has heard,

Beyond the noise of Nasir Bagh,

The breathing of the One

At whose mercy

She is permitted to continue

To exist. Let it be so.

And may Allah, the Most Forgiving One,

Seal up our unintended wrongs,

Missteps, split-second acts,

Mistaken deeds, and sins

We didn’t mean, and couldn’t know,

In what we’ve said or done. Amin.

But if this cannot be,

Then, even so,

Kind angels, come.

♦

The cameras are haram—though once,

In afternoons as white with heat

As if the world were just created,

Her people crouched

On their haunches in the flatbeds

Of pickup trucks parked

At the edges of brown cliffs

And square-miles-deep sequences

Of floating ravines,

And turned to look into the lens

Of the war journalist

With the over-the-shoulder glances

Of trotting wolves.

Their drama of ghost-tangled beards

Astonished the camera,

Their eyebrows the color

Of campfire-incinerated

Lapis lazuli, their black-iris glares,

Their elegant, narrow skulls

Wrapped in the headgear

Of turban-crowns:

Exiled viziers, household Sennacheribs,

Wielders of Bronze Age shears,

Uprisen

Biblical counselors,

Underestimated

By numberless, forgotten kings.

“Soft is the tongue of an overlord,”

Said Ahiqar,

“But it can break a dragon’s bones.”

♦

Though, when captured,

Their likenesses are hidden,

Since photographs

Are as forbidden at the black sites,

As haram,

As pictures in the holy Qur’an.

But pictured in the Assyrian

Bas-reliefs from the 600s BCE,

Carved in white alabaster

Now stained with iron, we’ve seen

The rope-bound shufflings

Of the mujahideen,

Dragging their knees:

Exhausted lions, filled with arrows,

Clutching at kings.

♦

We’ve seen them as if

Through old, exploded dust

When a jagged hole

Is punched into sandstone

And a jittering light beam

Touches a far wall:

Captives of Pharaoh

Painted in profile in dark red tempera

On the sandstone walls

Of Egyptian tombs,

Shoulders rope-bound to planks

And elbows twisted over their heads

And tied to chariot wheels—

Frogmarched, single file,

To the floodlit concrete rooms,

They join the ordeals

Of captured Hittites, Babylonians,

Libyans, Nubians, Asiatic Greeks,

Hebrews, Cretans, Eastern

Iranian tribal dynasties

And nameless peoples from “unknown

Lands beyond.” Triumphant

Hieroglyphic execration texts

Surround their heads

With curses, and prayers

For the smiting of foes, like scorpions

Racing their shadows.

♦

The tenth-century Arab geographer,

Al-Muqadassi,

Renowned as a genius unparalleled

Among the preeminent sons,

Imams, calligraphers, and scions

Of his native Jerusalem,

Recorded, in his splendid script,

A maxim that was ancient

Even then:

“Jerusalem, it is written,

Is a golden basin

Filled with scorpions.”

♦

She stands still, as if charmed:

In the enchanted grip

Of Kodachrome,

A pair of eyes

Bears witness that there is

One God alone.

“Surely Allah does not do injustice

Even to the weight

Of an atom.”

And surely those who do

“An atom’s weight of good”—

They shall see God.

As we shall, when we sift

The particles of what we’ve pulverized,

Searching for what constitutes

An atom’s weight of good,

And find, however far

We break the fragments down,

Each fragment is a whole.

Each whole,

Immeasurable.

And weightless as a gaze

That tells

The story of a soul.

♦

Even the thin, tawny feet

Of the mujahideen

Look Allah-haunted and gaunt,

Nearly weightless,

Tethered at the ends

Of their loose trousers,

Like the feet of eagle skeletons—

The eagles Solomon

Once posted as bodyguards

To guard the corpse

Of the prophet David

In the blistering Sabbath heat,

Shading him with their wings.

The magic law of torture—

Your captives are your captors—

Remains in force long after

Their feet are no longer swollen

And the imprinted patterns

From their lost plastic sandals

Have long since faded.

Like Solomon’s raptors

Caught in the naked gorges

Beyond Jerusalem, they’re transported

In the sort of iron cages

Still in storage at our undisclosed,

Ghost-mapped prison facilities

And military installations where,

Through the shadows of iron bars,

A Pashtun glare

Is a serpent

Held up in the air

In a wilderness

Of metal shipping containers.

And when the Lord in His mercy

At last casts a spell of sleep

Over these “enforcers

Of the dictates of custom,”

And they lie in a heap

On the hosed-down cement,

They sleep the sleep

Of haggard sorcerers,

Incapable of defeat.

♦

Though we know a thin-section

Of agate would have had to be

Gripped in a vise,

And cut transverse

With a diamond-edge saw,

And affixed to a slide, and ground

From its other side,

Wafer-thin,

With a grinding stone—

Though we know its

Interior lamina-glow

Can be only attained

With abrasive force at a polishing wheel,

With coarse-grained particles

Of carbide grit—

Still, the sheen of a cut-open stone

Appears merely daubed

By an unseen

Feather-brush dipped

In amber resin glaze,

For one purpose alone—

To hold up to the streaming light

Of God the image of

A tent-lit gaze

The color of cut-open agate,

Mined from the green rift

East of Kabul.

Or thin-cut jade. Or light-green,

Banded malachite, used,

According to legend,

For the protection of a child.

Or the half-remembered,

Half-forgotten shade

Of ancient jasper,

Known as “plasma green.”

She turns to look:

Salt green

Of the jugular vein,

Seen from the outside.

In the words

Of the Messengers of Allah:

We are as near to you as the jugular.

And in the words of David,

Speaking to God:

Your arrows have sunk into me.

She turns to look,

And a flock of arrows

Falling far and wide

Over the face of the earth

Comes to a standstill overhead.

Selah.

♦

According to Leviticus Rabba,

No force exists that can dislodge

A single word of Holy Law.

“Should all the nations of the world unite

To uproot one part of it,

They would be unable to.”

In Psalm 33,

He spake, and it was done;

He commanded: and it stood fast.

So too, in the vellum

Of the noble Qur’an, the ink

Has dried, and not an atom

Of a single stroke of ink

May be subtracted from

What’s written there. Or added to—

♦

But to the list of weapons

Mentioned in the Qur’an,

Arrow, coat of mail, knife—

The arrows of the infidel,

And the coat of mail David forged

With the help of God,

And the knives

With which the women cut their hands

Out of astonishment

At what they had seen—

An angel entering in

Through the door of a tent

When no one expected him—

To the list of weapons mentioned

In the Qur’an, add this.

This glance.

At which our hearts

Have smote us from within.

Gjertrud Schnackenberg in Conversation with Susan Gillis and Gregory Fried

Susan Gillis

I was enjoying my second coffee on a quiet morning some time ago when this message from Gjertrud Schnackenberg arrived in my inbox.

Dear Susan, At last I’ve finished the poem I’ve been working on day and night since October, 2012. When I began the poem I was overjoyed because I thought it would be a short poem, and I always want and hope to write short poems — but as weeks turned into months and years, the writing began to feel like a dream in which I was using magic scissors to cut into it and cut into it, and with every cut, the poem grew longer and longer.

She had attached a file. I put down what I was doing and opened it, and began reading. And re-reading. It was, to put it simply, astonishing.

“Afghan Girl” (New England Review, June 2017) pays tribute to Steve McCurry’s iconic photograph of a young woman, later identified as Sharbat Gula, in an Afghan refugee camp. Her arresting gaze is the starting point for Schnackenberg’s interrogation of conflict, empire, religion, beauty and presence. It’s a poem that meets the gaze of Sharbat Gula with its own intensity, unfolding in rhythmically propulsive short lines its quest to understand what that gaze expresses and what it stirs in the viewer.

I wrote back. How do you do it, break my heart in a poem and lift it up at the same time? The conversation that follows, with the kind participation of Gregory Fried, is Trude’s extended answer to my question. Gjertrud and Gregory spoke with me via email over a period of several months.

Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl,” image taken in 1984.

SUSAN GILLIS: Your poem “Afghan Girl” opens on Sharbat Gula’s gaze as it is caught and held in Steve McCurry’s photograph. Let’s begin there, then. Is it fair to say the poem is one in which image-making as subject is explored through image-making?

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: Image-making as a way of exploring the image, and of exploring the insuperable drive to make images—yes, and the poem seesaws between the opposing facts that human images are prohibited in Islam, and that this photographic image of an Islamic girl is one of the most famous photographs in the world.

In reference to the paradox of this poem’s subject, an image taken from an image-forbidding culture, the poet Mary Jo Salter has spoken of “the unwinnable, unlosable argument of imagery.” Her phrase goes directly to the heart of how poetry thinks, and I think it furthermore hints at the bond between imagery and negative capability. That is, the way that poetry thinks, which is so often in imagery (and in imagery that imagines thoughts about images), is one of the ways that poetry slips the cuffs of ideologies and beliefs (and of the self and its viewpoint, too) while retaining the value, even the moral value, conferred by witness.

SUSAN GILLIS: One image in the fourth section, toward the end of what I feel as the poem’s opening movement, strikes me quite forcefully as an example of this kind of thinking. A “wind-accosted . . . nest/Built on a precipice” holding a “clutch of Persian Eagle eggs” launches the poem’s deeper inquiries into conflict, belief systems and history. The nest teeters but somehow holds, as do situations unfolding in the poem. It’s an arresting moment. Where did it come from, how did it come to you?

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: The “clutch of Persian Eagle eggs” was the first image that came to me as I began writing about this photograph. I was in Umbria, at the artists’ colony Civitella Ranieri, at the time—I remember right where I was standing. The image of the eagle eggs glimpsed in the nest seemed to be relaying the innocence and the wildness, the dignity and the fierceness, of her gaze. The constraint here, in the warning in her eyes, as it flashes an implicit, readily-understood forbiddenness of approach—in turn ignites one’s own reflexive fear of violating such a being, not only by looking at her, but even by simply becoming aware of her. The reference to Persia is an allusion to one of the numerous suppositions about the as-yet unknown origins of the Afghan people. And, of course, the gray-green tint of eagle eggs is a part of this.

SUSAN GILLIS: “Clutch” resonates both as the accurate word in the specific image and in its secondary reference to the poem’s momentum, which reaches and grips in continual expansion.

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: “Clutch” is a homonym here: her gaze clutches us. These and other of her qualities have always signaled, to me, a sacred presence. From the first time I saw the photograph Afghan Girl in 1985, and then in the many hundreds of times I have looked at the photograph in the course of writing this poem, each time I have been stunned—the impact of the photograph doesn’t lessen—at the way the image of this child evokes, for me, an image of Mary of Nazareth. In the sixth section of the poem she appears, briefly, as an image of Maryam in the Qur’an. I don’t know whether this association is only a singular, private one for me, or one which others have noticed and felt too, but her association with Mary has never faded from my response to her.

When the photograph was published in 1985, one could almost hear a collective, worldwide gasp. It expresses a beauty so intense it seems to hint at something we habitually prove to be untrue: that the force of beauty could be sufficient to interrupt our perpetual wars. And in its expressing a beauty so pure, we may feel as if we are in the presence of a promise being made to the earth—a promise difficult to put into words, a promise made in imagery—imagery being, apparently, as far as I can discern, the chosen medium of the divine imagination.

SG: I’d like to hear more on the subject of beauty, but first: Your reading of an implicit warning in her eyes together with the association to Mary of Nazareth sends me back to the poem’s first lines:

As if broken in upon

By the spirit of God

and then to section six, after Maryam has entered the poem, to an image in a mosque mosaic of a “suddenly broken law.” Breakage in the poem is associated with interruptions both productive and destructive.

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: A sacred breaking—I do understand breakage-in-continuity as a way of describing the sort of spiritual experience that opens this poem, but I want to be careful with where and how this metaphor extends. That this young girl is “broken in upon” is a sheer fact of the photograph’s historical background, given that the photographer found her when he entered a tent that was set aside strictly for girls, in the context of Pashtun cultural rules in which females are routinely separated and sequestered. Her expression’s aura of divinity is intensified, in part, because a photograph confirms a break with and from chronological time—and here confers its own eternity on this encounter.

And the mosaic, as an ostensibly shattered image, is of course not broken, but on the contrary deliberately pieced together for the purpose of portraying a totality rather than fragments (and for portraying a totality by means of fragments finding one another). A mosaic image also seems a metaphor for the kind of spiritual revelation (Hebraic, Christian, Islamic) which can be a shattering event even in its revealing of fusion, or union, and the having of contact with what is whole and entire.

But again I want to be very careful with this metaphor, because this is a wartime image, and we know that war is eating at the margins of the photograph. War, as an ultimate embodiment of breakage and ruination, ushers in torture as the ultimate breakage humans can perpetrate or experience. Breakage in the poem is, as you say, both productive and destructive, both cause and effect, both divine and human, with outcomes both wondrous and horrifying.

SUSAN GILLIS: Interrogation as act and as concept is both explicit and implicit in the poem. I’m thinking here not only of the poem itself as an interrogation, but also of its references to excavation of ancient sites and the way you harness ancient scripts and text images to contemporary scenes/acts of prisoners, refugees, transfer of people in the poem’s later sections.

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: Images of war in ancient poetry and wall paintings and bas-reliefs from ancient Egypt, from Babylonia, from Sumeria, from the Hebrew Bible, from the Iliad, and from many other sources—images of prisoners of war, and refugees, and torture, and transfers of people—are modern in their horror and ferocity.

Painted frieze in Medinet Habu Temple. Image courtesy Andrea Salimbeti

More than a decade ago I saw a sickening photograph (which has now apparently disappeared from the internet) of a line-up of Taliban prisoners bound together with a rope, or a leash, seated and waiting to be led by their American captors into prison. It wasn’t only the impact of seeing men leashed that was so sickening, but I felt a shock that the photograph was almost a reworking of those ancient Egyptian wall-paintings of captives being pulled along, with their arms tied over their heads and bound to planks and wheels by a rope, or captives seated, leashed.

The horror that torturers, when captured, are, in turn, being tortured, is almost too demonic an equation to write down; and to think that my own country, the United States, commits torture is as terrifying as it is to think of American prisoners of war being tortured. The poem had to acknowledge, at the same time, the truth of American violence and the bigotry that makes torture possible for the torturers, as well as the violence and bigotry of the Taliban and the torture the Taliban perpetrates.

Two different sources in the ancient world supplied the phrase “Your captives are your captors”—first from the Book of Isaiah, and then, centuries later, from Horace. Isaiah 14:2 says: “Nations will take them and bring them to their own place . . . They will make captives of their captors and rule over their oppressors.” Horace wrote nearly the same words about the Romans’ adulation of Greek art: “Captive Greece made captives of her captors.”

SUSAN GILLIS: The association of beauty with the divine, as distinct from the erotic, and the promise or hope that its “force . . . could be sufficient to interrupt our perpetual wars,” seems especially relevant in this era of increasing populist nationalism. Was writing the poem in any sense a political act? Is reading it a political act?

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: Although this poem is filled with political matter and consequences—war, refugee orphanhood, religious conflicts—even so, I think of this poem as other than political; I think of it as ekphrastic, and religious. Perhaps this is partly because I do think it would be odd, in our era and culture, for a political poem to be a poem about the beauty of an image, given that in the twentieth century the critical and theoretical assault on beauty was fundamentally a political, or politicized, theory (and was itself, ironically or paradoxically, an intellectual fashion): that beauty, or “beauty,” is superficial, misleading, privileged, elitist, easy, morally deficient, conventional, unchallenging, illusory, or offensively pretty in a bleeding world. In its American manifestations, the critical objection to beauty, however defined, as not worthy of serious consideration in art, is, I think, at its source, puritanical—in my time our puritan heritage has resurged in all manner of wondrous ways, with the content reversed, but the attitude intact.

Obviously, beauty—like poetry—can’t be defined, and obviously, whatever it is, its manifestations are numberless across human histories and cultures, but it seems to me that theorists who oppose the principle of beauty in art must erroneously have found the cosmos to be exhaustible, and must believe themselves to have, and must wish to persuade others that they have, exhausted it. I can’t argue about this, but I would ask if any of these judgments about beauty—as privileged or elitist or superficial or morally deficient—pertain to the beauty of the “Afghan Girl” photograph.

SUSAN GILLIS: Beauty is also, in the poem, a repository of history—

In a glance,

An overhanging sense

Of Pashtun magnificence

A glance that is at once hostage

And its own

Immeasurable ransom

and a signal of the riches of creation, one of several kinds of quarrying the poem undertakes to represent:

A roughed-out chunk

Of aquamarine

Unpolished, uncut

Recently clawed

From the gem-bearing pegmatite

In the cliffs of Nuristan

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: I think that artists are able to painlessly suppose—and poetry and literature are indefatigably suppositional—that beauty may well be useless (as is much of the cosmos), and vastly extra. I am much too absorbed by the theory of evolution to maintain that supposition for long, but I want to say that artists, throughout time, seem to me willing and able to suppose that, if beauty is useless, its wonder is not lessened, and that its presence is not diminished if it doesn’t do anything, other than to exist as itself, as what it is. And even if beauty isn’t useless, or extra, I can never forget Shakespeare’s description of beauty, in Sonnet 65, as an “action.” If beauty is an action, then perhaps its purpose, or at least its outcome, is to disclose.

But to disclose what? You’re right that I associate beauty with divinity—and divinity with creation, and creation with beauty. I believe that the experience of beauty is an animal-kingdom birthright, as in Carl Sagan’s statement that “It is the hereditary birthright of every child to encounter the cosmos anew.” Or as in the Heraclitus fragment, more briefly: “The Kosmos, common to all.” Unless we are indoctrinated otherwise, or impeded, or irreparably disillusioned as toddlers, we all have seen or felt or heard or known (and artists have tried to recreate, in homage) some tiny fraction of creation’s beauty.

But why and how I see divinity in these fractions would have to be for another conversation.

SG: You spoke of a bond between imagery and negative capability in terms of—and I love this expression—“slipping the cuffs” of ideology while retaining the value conferred by witness. Could you say a little more about this bond, or these qualities?

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: Whatever the intent and import of political poetry as a genre, for me there are other, higher values moving across—and all the way to the other end of—the spectrum of poetry’s genres, away from political and ideological convictions. One of the reasons I cannot imagine trying to get through life without poetry, and don’t want to, is, precisely, negative capability, and poetry’s surpassing ability to exist beyond argument, beyond polemics, beyond convictions good or bad, beyond the taking of sides, beyond the need to elicit agreement, beyond personal systems of belief and religions and cultures (all of which means, to me, that poetry exists beyond faith, beyond the violence that clings to systems of belief, and beyond war) even as it is able, when it is excellent, to comprehend and handle the stuff, the material, of any given argument or belief. (And, at the same time, miraculously, poetry’s voice is most often not a doubtful, skeptical, reluctant voice.) I like the paradox that something so rhythmically designed as poetry does not have a design on us, that its patterns are not seeking agreement, are not coercive. Perhaps the “argument of imagery” is the same as imagery’s inarguableness.

I like the paradox that something so rhythmically designed as poetry does not have a design on us, that its patterns are not seeking agreement, are not coercive.

SUSAN GILLIS: Soon after you finished writing the poem, you wrote to tell me that a family friend had made what you called a startling discovery about the photograph in relation to the last section of the poem.

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: Yes, Gregory Fried’s discovery is a marvel to me. Gregory is a former student of my late husband’s, and the son of friends, and a professor of Philosophy, and, little did I know, a daguerreotype researcher. I was visiting his parents one evening when Gregory, who had read my poem and then searched online for an image of the Afghan Girl photograph, called me into the television room, where he had plugged his iPhone into the television in order to display the image of Sharbat Gula’s eyes, magnified many times. I was floored by what I saw on the screen. But the discovery is his—he should tell the story.

SUSAN GILLIS: Gregory, thank you for joining in. It’s no surprise that after reading the poem you’d go in search of the photograph it responds to; where did the impulse to magnify it come from? What were you looking for in the image, and what did you find?

GREGORY FRIED: As you two have discussed, the portrait of Sharbat Gula is so powerful because of the transfixing gaze of her eyes. In reflecting on the poem, when I first read it months ago, it hit me that reflection might be more than a figure of speech in this case.

This occurred to me because of my fascination with very early photography, from the 1840s and 1850s when the art was in its infancy. At that time, the most prevalent form of photography was the daguerreotype. The daguerreotype process was a marvel of alchemical conjuring, involving the preparation of a silver-coated copper plate sensitized with iodine and bromine vapours, exposed in the camera, developed over heated mercury fumes, fixed in hypo-sulphate, and finished with a bath of gold chloride. Each image is a singular object; there is no negative for reproduction. The resulting photographs are often exquisitely haunting, with an almost holographic effect.

In my work with these early photographs, I have sometimes been able to open windows onto the world captured in an image because, in many cases, the resolution is so precise that tiny details are visible under strong magnification. For example, I have been able to date an image by the stamp on a letter, discover a location by a flyer posted in a window, identify a soldier’s unit by the design of a button on his uniform, and unearth an identity from a stencil on the leg of a folding camp chair.

Details of Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl”

The specialized literature on daguerreotype includes writing on extreme cases of this detailed resolution* (see Note, below). While there is debate about this, some have attempted to show that in some portraits, the maker’s technical skill was so good it is possible to see details of the photographer’s studio reflected in the subject’s eye.

It must have been remembering this literature that nudged me, in the hour before Trude arrived, to seek out a digital version of Steve McCurry’s iconic portrait. Without much difficulty, I found a high-resolution version and, when Trude arrived, displayed it on the digital television, where we viewed it in very large scale. It seemed unmistakable: there in Sharbat Gula’s eyes was a reflection, not just of light, but of the scene before her: a glimpse of the refugee camp, Nasir Bagh, through a rectangle of light that must be the opening to the tent.

It was Trude who realized that this scene, especially in the eye on the viewer’s right, might include McCurry taking the photograph from the entrance of the tent, the flap open to the light outside. As I saw it then and still see it now, someone is clearly there, in wispy outline, to the side of the entrance, and I do believe it is McCurry, taking this very picture. Other photographs of the refugee camp show it as a cramped jumble of makeshift tents, and what I think I see beyond the tent opening is the ground, then some of those other tents in the near background, and then the sky above.

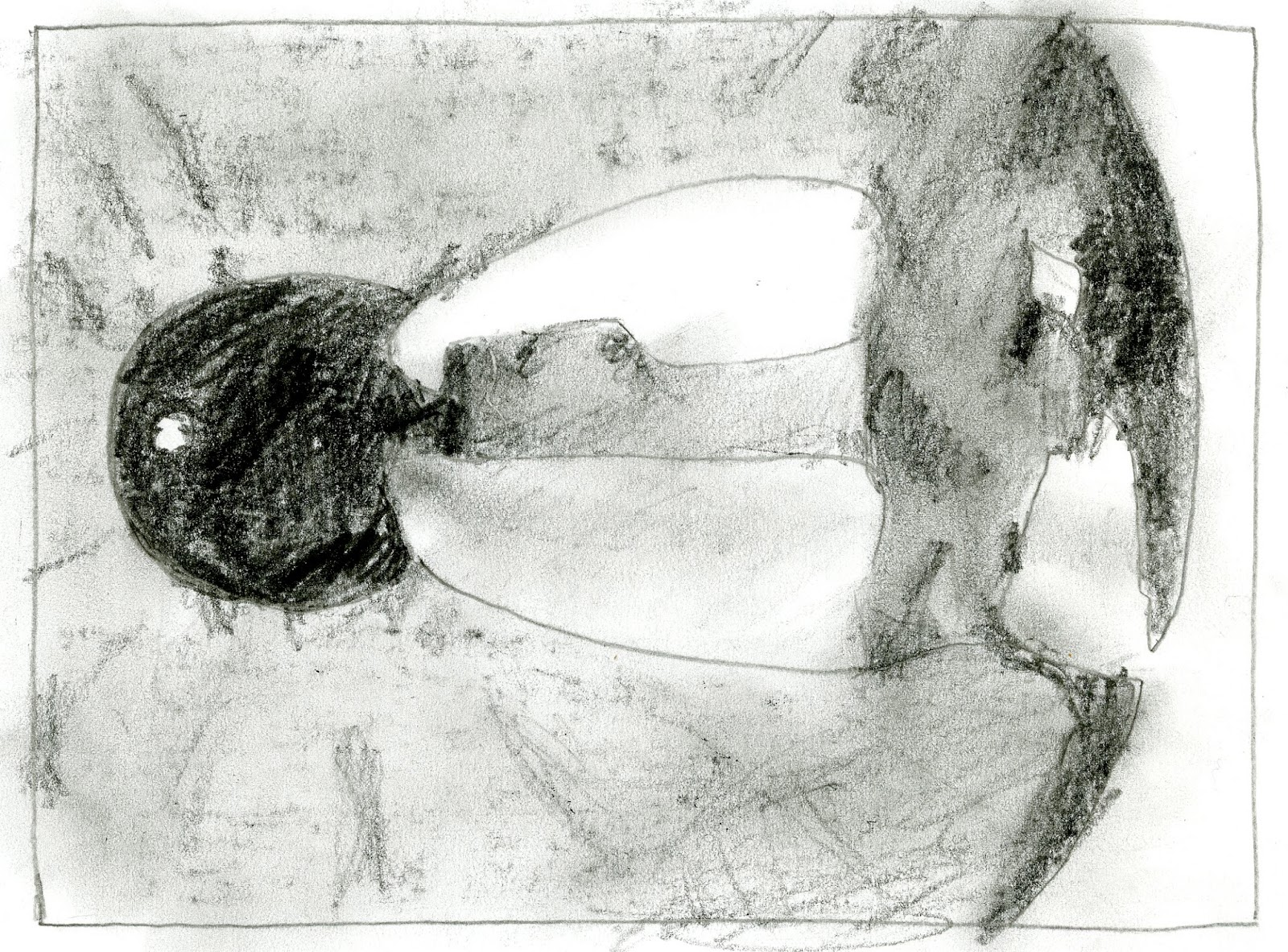

Detail Sketches by Gregory Fried of “Afghan Girl”

It is worth noting just how tiny these details are. The illustrations here of her left eye give some indication. Only with a very strong magnifier or digital imaging technology can one draw out these details.

SUSAN GILLIS: What were your reactions, both of you, when you observed this? Is it possible to say with certainty that it’s the image of Steve McCurry?

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: For me, a gasp, and waves of goosebumps. It was one of the greatest surprises of my life. Of course, it is incontestable that the photographer would have been there, in front of her. This does not need to be confirmed. But what is not at all obvious, at least to me, is that, at the moment his camera recorded her image, her eye would have recorded his image too, and that his camera was recording her eyes as her eye recorded his image.

GREGORY FRIED: As for the figure ostensibly reflected in her eye: I don’t think there’s quite enough detail to say with absolute certainty, but as a matter of optics, it makes sense that the person standing in Sharbat Gula’s direct line of vision (she is looking into the lens) would be the photographer. My guess is also that for the proper lighting, the photographer would position himself between the opening to the light and the subject of the portrait. It adds up, for me, to a very high probability.

Detail Sketches by Gregory Fried of “Afghan Girl”

SUSAN GILLIS: Trude, your poem ends with a reference to a passage in the Qur’an that includes a vision of

An angel entering in

Through the door of a tent

When no one expected him

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: I was and remain agog to see that the very poetic Qur’anic incident (at 12:31, when Joseph enters the place where the women are gathered, and the astonished women exclaim that he is not a man, but an angel)—that this Qur’anic incident corresponds so closely to this image recorded, in the starkest reality, by a camera.

There is a final, supernal touch given to this incident, in the quality of the image of the photographer we see magnified in her eye’s reflection: his image—if it is his image—is extremely blurry, indistinct, and, in the magnified version I saw on the television, very brightly lit, so that it looks as if he is arriving at the door of the tent with angelic speed, surrounded by overlapping layers of radiance.

One of the strangest experiences of writing poems is that poems can ‘come true,’ and do so in completely unexpected and startling ways, long after they’re finished and done with. But this is the most overwhelming example of the phenomenon that I’ve ever experienced.

One of the strangest experiences of writing poems is that poems can ‘come true,’ and do so in completely unexpected and startling ways, long after they’re finished and done with.

I meant this poem as an homage not only to the holiness of the beauty of this child’s glance, but as an homage to the photographer, who, in my opinion, is one of the most accomplished artists of our time.

But to return to earth and Nasir Bagh again: Steve McCurry has said that moments before he encountered her, as he was walking through the refugee camp, he overheard the sound of girls’ laughter. He sought out the source of the laughter, and found the tent where a temporary girls’ school had been set up. When the teacher saw him looking in, she beckoned him, and asked him to take a photograph of their circumstances (a boldness on her part, given that a foreign man properly should not have been in the girls’ classroom), because she wanted the outer world to see the conditions of Nasir Bagh. When he came in, he immediately saw the eyes of the girl whose name we now know to be Sharbat Gula.

GREGORY FRIED: I love this story, as it gives such important background to the moment captured. You said earlier that we are possessed by “the insuperable drive to make images,” and yet this comes into tension with an “image-forbidding” religion and society. You also mentioned moments of “sacred breaking” that throw the given world off its axis, such as the apparition of the angel. What struck me here is that such a breakage—in this case, a break in the opposition between image-driven and image-forbidding impulses—occurs because of a trauma, a break, in the lives of these Afghan people in a refugee camp. The teacher summoned McCurry, allowing and even encouraging this rupture of tradition, in order to communicate to a larger world the condition of the people in the camp.

SUSAN GILLIS: Let’s return, then, as the poem so often returns, to Sharbat Gula’s eyes, not only their colour but all that is held within and hovering beyond the reach of their gaze. Or is it the photographer’s gaze? Or is it ours? Anyway, it is an extraordinary convergence of effects.

GJERTRUD SCHNACKENBERG: And an extraordinary convergence of gazes—all of our gazes. Your phrase, “an extraordinary convergence of effects,” is wonderful and more telling than you may realize, given that Steve McCurry himself has spoken of this photograph, in an interview, as a life-altering instance in which all present elements came into a split-second alignment. The photograph eternalizes a moment in which unnumbered accidental aspects, known and unknown, suddenly commove and converge, in order to gather her presence and his presence together. Such a convergence seems more like something out of literature or poetry than reality.

And yet it is real. When poetry is at its uttermost, it converges with truth—the truth of human experience—but here is a moment when poetry and truth together converge with reality.

SUSAN GILLIS: Thank you, Trude, for the poem and for sharing the inner working of its making. And Gregory, for your work with the image. You’ve both been remarkably generous.

Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s most recent book, Heavenly Questions, won the International Griffin Prize in 2011.

Susan Gillis is the author of three collections of poetry: Swimming Among the Ruins, which was shortlisted for the Pat Lowther Memorial Award and the ReLit Award; Volta, which won the Quebec Writers’ Federation A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry; and The Rapids, which was a finalist for the Quebec Writers’ Federation A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry.

Gregory Fried is Professor and Chair at the Philosophy Department at Suffolk University. He has taught at the University of Chicago, Boston University, and California State University LA. His research focuses on defending the Enlightenment tradition against its critics, most particularly Martin Heidegger.

This interview was originally published in Concrete & River and “Afghan Girl” was originally published in the New England Review, June 2017.

* Note: see article by JoeBaumann, “Daguerrian Glimpses,” in The Daguerrian Society Newsletter, Jan-Feb 2005 (Vol. 17, No. 1).