William Shawn and Roger W. Straus Jr., the president of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were friends across the years, and in 1987 Roger actually hired Mr. Shawn, setting up an office for him in Union Square, after new owners of The New Yorker accomplished for Mr. Shawn, with respect to retirement, what he had no sincere interest in accomplishing for himself. The dissimilarity between Roger and Mr. Shawn could not be exaggerated. They were a pea and a prawn in a pod. Shawn grew up in the middle of the merchant class. Roger was born with a copper spoon in his mouth: the Kennecott Copper Corporation, American Smelting and Refining. His mother was a Guggenheim. Shawn was as shy as he was soft-spoken. Roger was a fountain of garrulity. Words came out of him so fast that he tried to economize by saying, at the end of every other sentence, “et cetera, et cetera, and so forth, and so on.” If something was marvelous, it was “mawveless.” His words wore spats.

He was a publisher, not an editor, but his conversational attention to writers was, to say the least, voluminous. He nagged a little. Oddly, it was he who would ask when was I going to get my act together and finish some piece for The New Yorker, while Shawn, in twenty-two years, never did. But mostly, with Roger, it was just talk—in person from time to time, but mainly on the telephone. I was a beginner when he began that. He published my first book, in 1965, and he called maybe forty times a year for something close to forty years.

Roger belonged to the Lotos Club, an institution housed in a mansion on the Upper East Side and devoted to literature and art. In the early nineteen-nineties, the club planned a state dinner in Roger’s honor and asked me and Tom Wolfe, as FSG authors, to speak. When the day came, and my turn came, I said, “I hope you don’t mind if I speak from notes. In an author-publisher relationship of nearly thirty years, this is the first opportunity I have had to get some words in edgewise, and I don’t want to let even one of them get away. Last fall, after I was invited to speak here on January 30th, Roger Straus soon called me to say that this was entirely the club’s idea, et cetera, et cetera, and so forth, and so on, and definitely not his idea. ‘In fact,’ he said, ‘I told them I didn’t think you were very bright.’ He said that he did not want me to feel any obligation whatsoever to him. There was no need for me to have to come all the way in from Princeton. Et cetera, et cetera. And so forth, and so on.

“I said, ‘That’s not the issue, Roger. That’s not what we’re discussing. What I need to know is, Is it all right to say “Fuck you” in the Lotos Club?’

“He said, ‘I see the lines along which you are thinking. Of course it’s all right. It’s perfectly all right. And, besides, you’re not a member.’ ”

When I was quite young, I was inadvertently armored for a future with Roger Straus. My grandfather was a publisher. My uncle was a publisher. The house was the John C. Winston Company, “Book and Bible Publishers,” of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and on their list was the Silver Chief series, about a sled dog in the frozen north. That dog was my boyhood hero. One day, I was saddened to see in a newspaper that Jack O’Brien, the author of those books, had died. A couple of years passed. I went into high school. The publishing company became Holt, Rinehart & Winston, and my uncle Bob’s office moved to New York. When I was visiting him there one day, a man arrived for an appointment, and Uncle Bob said, “John, meet Jack O’Brien, the author of Silver Chief.” I shook the author’s hand, which wasn’t very cold. After he had gone, I said, “Uncle Bob, I thought Jack O’Brien died.”

Uncle Bob said, “He did die. He died. Actually, we’ve had three or four Jack O’Briens. Let me tell you something, John. Authors are a dime a dozen. The dog is immortal.”

As I have mentioned before, in various places and publications, Roger Straus would have understood not only my grandfather but also my great-grandfather Joseph Palmer, a farmer who had a mill pond and a sawmill on Doe Run, about thirty miles west of Philadelphia. He made, among other things, book boards—the hard parts of what are now called hardcover books. He sold them to Charles Ziegler, my great-uncle, who owned Franklin Bindery, and whose best customer was the John C. Winston Company. Winston claimed to publish more Bibles than anyone else in the world, and at the other end of their list was my grandfather’s specialty, the hardcover equivalent of the newspaper extra. In 1912, he published a quickie on the Titanic while the bubbles were still numerous and the ice had yet to melt.

Being a publisher, my grandfather naturally kept a pair of pearl-handled .44-calibre Colt Peacemakers in a velvet-lined box in his study.

Being a publisher, my grandfather naturally kept a pair of pearl-handled .44-calibre Colt Peacemakers in a velvet-lined box in his study.

I dealt with Roger Straus without an agent. Contractual negotiations took place in private conversation between us. I risked foolishness. I once asked Roger, “How much money am I losing as a result of not having an agent?” And he answered, “Not a whole hell of a lot.”

One time, when he was contracting to publish a hefty hardcover book with my name on it as author, I asked him for an advance, and he said, “Fuck you.” That is exactly what he said. Truth be told, though, the book was an amalgam of fragments of other books, for which he had long since paid advances.

He always said that he wanted to publish authors, not books. This principle contained not only an admirable loft but also a faint implication that if you had a dog you could bring it to the party. In 1968, when we talked about publishing what was to be my fifth book but first collection of miscellaneous pieces, I said to him, “This one isn’t going to make a nickel. Collections never do. I’m grateful to you just for publishing it. Don’t bother to pay me an advance.”

“Nonsense,” he said. “I’m your publisher. Of course I will pay you an advance. I insist.” And he named a sum so low that I am somewhat shy to reveal it.

In fact, it was fifteen hundred dollars. The book was published in 1969. It did not do well over the counter. It took fourteen years to earn back the fifteen hundred dollars. Notice something, though: after all those years, it was in print. Commercially, that book could not have been a bigger dog if its title was Remainder. In conglomerate publishing, it would have vanished three weeks after it was published. But Roger kept it in print, as he kept all my books—marginal and otherwise, hardcover and soft—in print. When I cashed his checks, I could hear the tellers giggling as I walked away, but even in my Scottish core I really didn’t care. Across the first decade of the twenty-first century, that ancient collection of miscellaneous pieces sold about seven hundred copies a year. A small figure. But for that book—for any trade book—forty-some years is an amazing longevity. Thanks entirely to its publisher. The dog is immortal.

At the Lotos Club, after telling some of those stories, I said, “Tom and I are here because Tom is the house eagle and I am the company mule. I say that with no false humility. I say it as plain fact. I would not know how to light a bonfire if someone handed me the match. I write about geology. In a sense, I am selling rocks. In Union Square, I know a sucker who will buy them.”

In 1975, I began teaching my course in factual writing at Princeton. Annually, until after the turn of the millennium, Roger drove down in his Mercedes and talked nonstop to the assembled students—et cetera, et cetera, and so forth, and so on—with a cumulative rate of repetition of four per cent. He repeatedly came to the course in a period when his health was inconvenienced by cancer. The students were always well prepared to interview him, but one question was enough. “Could you tell us about Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn?” someone said. And Roger said, “Eighteen years ago, when I first started having serious intercourse with the big A . . .” and he was off and running for three hours of free association.

When The New Yorker appeared to Roger to be heading down some sort of tube, he came to my campus office and offered five independent book contracts aggregating a sum that would not impress a hedge-fund manager but might have impressed a literary agent had one been present—or, as I said at Roger’s memorial service, in 2004 at the 92nd Street Y, “It was enough money, actually, to keep me alive until this moment, which Roger may have had in mind. I’m a little sorry that I am speaking at his service rather than he at mine, because it would have been a lot more entertaining the other way around. I used to try not to think about the possibility that some day the dialogue would end, the hundreds and hundreds of phone calls, the flying humor. He was there in my thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties, and was still leading me up the street on a leash when I entered my seventies. If he kept back money that he might have laid on me, I’m particularly happy about that now, because I’m sure he has it with him, and he’ll need it.”

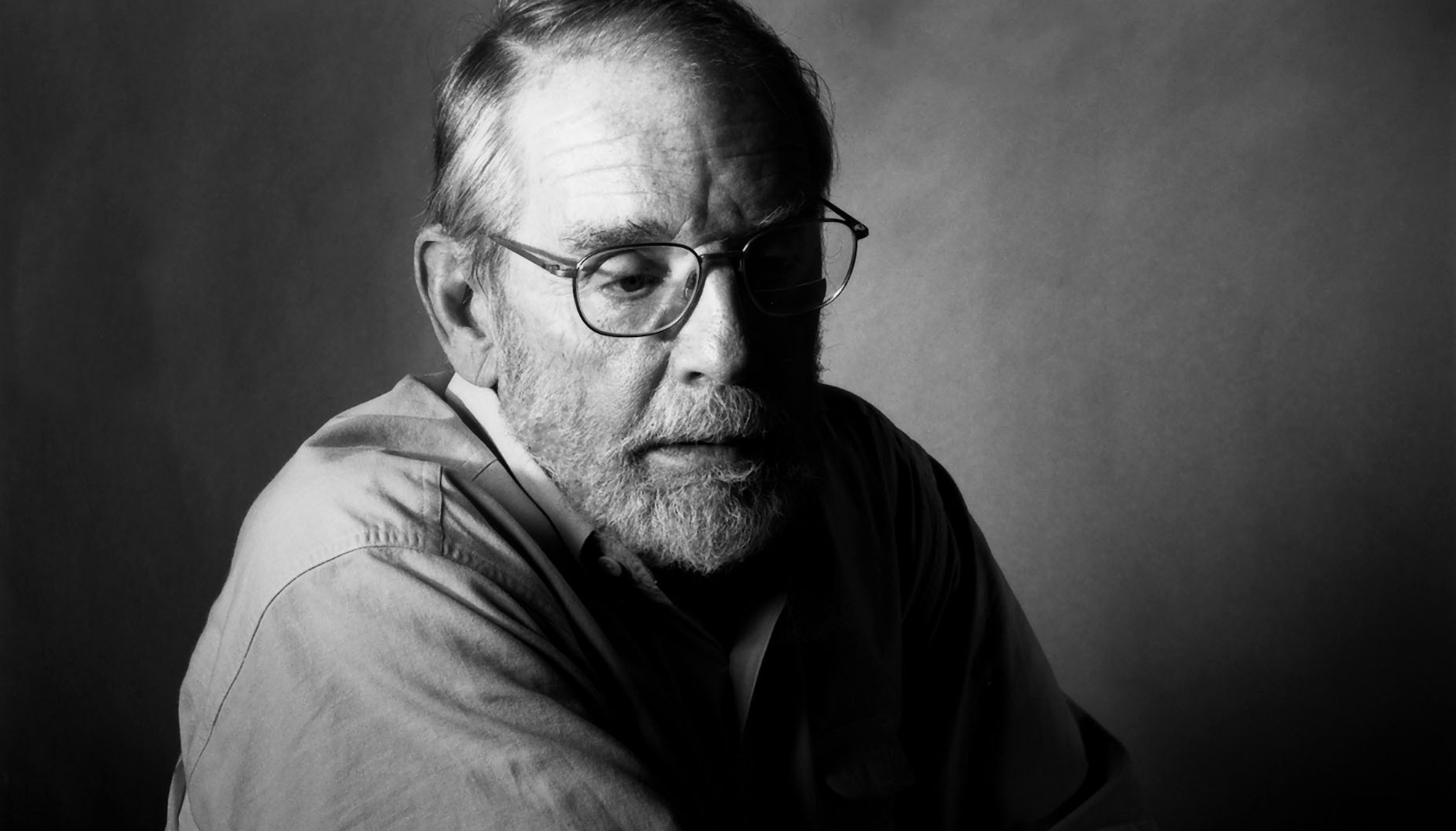

John McPhee is a staff writer at The New Yorker. He is the author of thirty-two books, all published by FSG. He lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

This excerpt was originally published in The New Yorker.