My first experience with Robert Lowell’s poetry was a failure in reading comprehension. Breezing through a stack of poems I’d been assigned for a college class, I came to his “Man and Wife” and gave it my cursory attention. Its setup is not hard to grasp: a married couple lies sleeplessly in bed in the early morning hours following a bad night, during which one has endured some kind of psychotic episode. I understood as much, but in my hurried reading, I reversed their roles, assuming reason in the (male) speaker, and madness in the woman by his side.

opens in a new window |

If poetry is generally not to be breezed through, Lowell’s poetry is particularly so. I have read “Man and Wife” many times since, closely and slowly; I even wrote about it for my undergraduate thesis. Still, reading it again brings about new impressions and renewed reactions to its multilayered language and turns of phrase. And now, the most salient influence on my readings is Lowell’s biography. Had I been familiar with it the first time around, I would have known that he famously suffered from manic depressive, or bipolar, disorder. I would have known about the remorse that overtook him in the periods following his manic episodes, as he made the rounds to acquaintances and friends with apologies, picking up the pieces of whatever he’d smashed.

Lowell’s life is a subject of enduring fascination, to which numerous biographies on him attest, including a new one this year that specifically examines his illness’s effect on his work, Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire, by Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison. His life is so obviously present in his poems that it’s nearly impossible to discuss them without it. So in “Man and Wife,” we find Lowell and his wife Elizabeth Hardwick, with whom he lived “on Marlborough Street,” as they “lie on Mother’s bed.” He describes how, outside the presumed window, “blossoms on our magnolia ignite / the morning with their murderous five days’ white.” History hangs over this scene of domesticity, in that the bed is an heirloom. But despite any sense of familial comfort, there’s an uneasiness in the way the bed remains “Mother’s” and not theirs. Over the magnolia tree, however, Lowell claims joint ownership. It boasts the paradox of menacing flowers—white, like hospitals, or weddings.

After my first, confused reading was corrected in a line-by-line classroom discussion, I decided somewhat arbitrarily that I wasn’t “into” Lowell. It would be nearly two years before I gave him a second chance. Rushing another reading assignment—this time a hefty section of The Letters of Robert Lowell, edited by Saskia Hamilton, my professor for both of the courses in question—my pace slowed when I encountered the magnificence of Lowell’s letters to Giovanna Madonia from 1954. I failed to put two and two together and read them without Lowell’s manic episodes in mind. (I was not always such a clueless student). For an afternoon, Lowell’s fervent letters to Madonia, an Italian woman he hardly knew, read to me not like the regrettable ravings of an unwell person that they were, but as the most spectacular expression of a person in love. Their bizarre intensity is irresistible:

My Dearest:

Well, I’m back a little earlier, writing a little earlier, and waiting for a letter a little earlier. I know I am a foolish man, but don’t keep me waiting—it’s like hanging on a meat-hook, going through a vegetable grinder, like being one of those pictures of flayed men—all purple and nerves—on an anatomical chart!

“I know I am a foolish man, but don’t keep me waiting—it’s like hanging on a meat-hook, going through a vegetable grinder, like being one of those pictures of flayed men—all purple and nerves—on an anatomical chart!”

Lowell’s letters on the whole are wonderful. He was known among his friends for their hasty composition—poorly typed, or illegibly handwritten—but years later, printed in a book, they feel as rich as anything over which an author might labor for hours. They are what got me, finally, very “into” Lowell. His letters lend his poems reality and an overarching narrative, while his poems distill the histories and impulses behind his letters.

Where Lowell’s poetry once struck me as formal and stiff, lacking the casual and visceral expression of other poets I was reading at the time—these ran a haphazard gamut from James Schuyler to Sonia Sanchez, to Olena Kalytiak Davis, to Kevin Young—his letters encouraged me to parse it. I came to find the most pleasure in Lowell’s writing in picking it apart, what with his propensity for double meaning—“old-fashioned” (26) in “Man and Wife,” as in traditional, and as in the drink—and for allusion, notably to classical mythology and to the history of New England, in which the Lowell family had been prominent since early Puritan days. Most characteristic, perhaps, of Lowell’s poetic style is his enjambment, the splitting of a clause by line break. It’s subtly unsettling, and ultimately very powerful, to leave things hanging in this way.

I remember looking back on my first reading of “Man and Wife” in disbelief that I could have misread it so terribly, embarrassed that I might be so socially conditioned to assume “craziness” in a woman over a man—especially after reading Hardwick’s incisive writing and understanding her role in Lowell’s life (in short: he was fortunate to have her). But returning to the poem, I can find reason for misinterpretation. Lowell writes of that morning:

All night I’ve held your hand,

as if you had

a fourth time faced the kingdom of the mad—

its hackneyed speech, its homicidal eye—

and dragged me home alive. . . . Oh my Petite

To be dragged alive sounds so far from a welcome rescue, it obscures what it means to face “the kingdom of the mad”—whether it’s her, in the kingdom, facing madness (being mad), or her facing him, the mad kingdom. With “my Petite,” Lowell launches into a reminiscence of the relationship’s early days; because his eyes are on her, it’s easy to read it as him mourning the way she used to be, instead of the way they used to be together. At the end of the poem, she lies “Sleepless,” clutching a pillow, and he writes:

your old-fashioned tirade—

loving, rapid, merciless—

breaks like the Atlantic Ocean on my head.

No one moves from bed, but Lowell interprets violence in all directions—from her, himself, the magnolia, “the rising sun in war paint.” It’s a testament to how, in partnership, the strains on one inevitably impress upon the other, with burdens shared as equally as comforts.

Lowell commands empathy in the first-person voice, delineating anxieties, affections, and regrets: his Life Studies, in which “Man and Wife” appears, was radically intimate when it was first published in 1959. He’s most potent where he counters general feeling with precise detail—“Man and Wife” calls out “the Rahvs,” Lowell’s friends, and “Miltown,” a name-brand tranquilizer introduced in the 1950s. This specificity in Lowell’s poems preserves the realness of his life. It designates landmarks and points of connection—I’ve been outside the house on Marlborough Street, posed for a photo on its stoop—and makes his writing something to inhabit. Reading, and rereading, Lowell prompts that level of involvement particular to poetry, which has a knack for making things personal.

Isabella Alimonti is an editor and writer. She worked in publishing after studying English at Barnard College. She lives in Brooklyn.

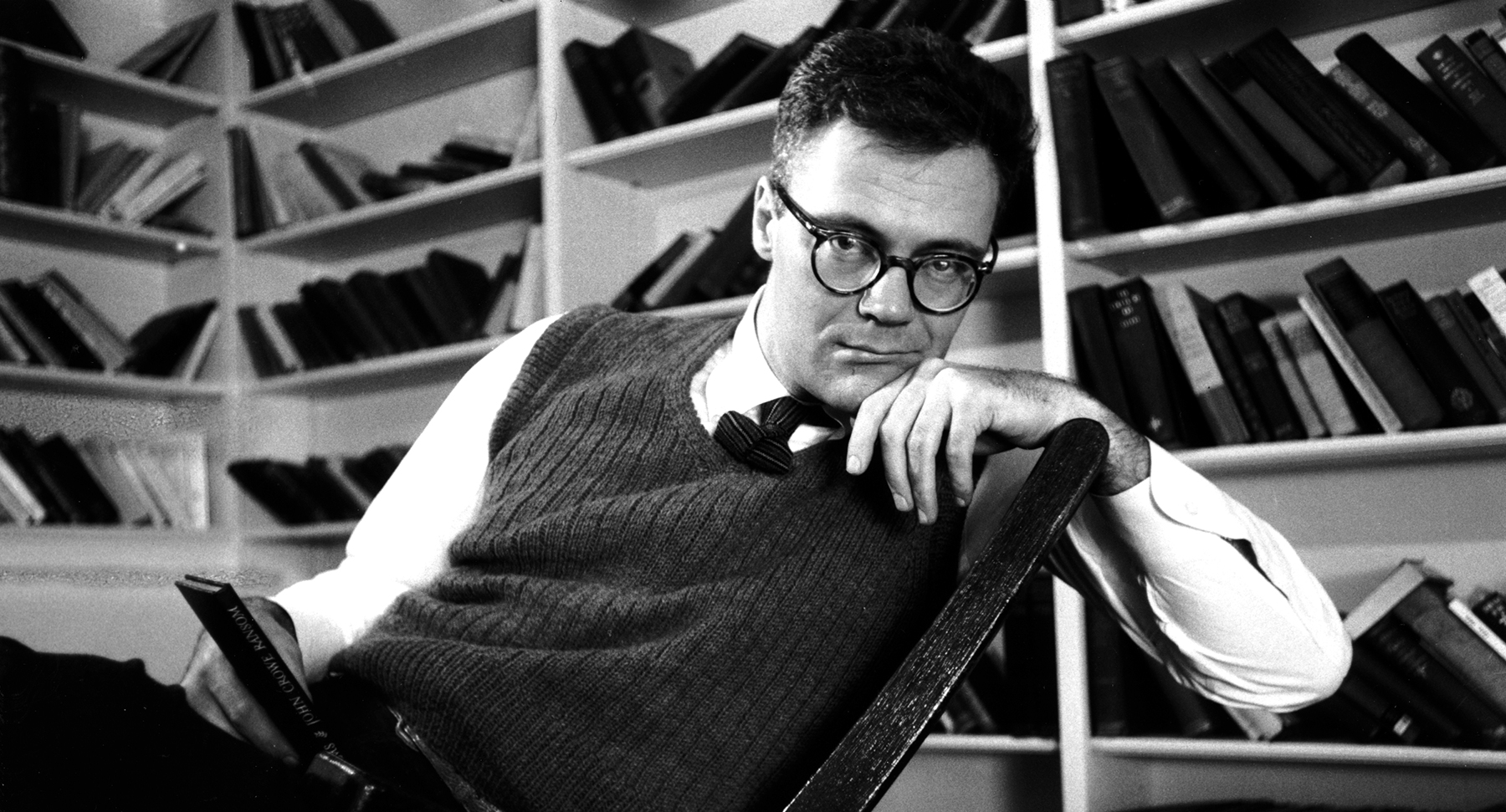

Robert Lowell was born in Boston in 1917. He attended Harvard University and Kenyon College, where he received his B.A. in 1940. He was the dominant poetic voice of his era. Lowell died in New York City in 1977.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE:

Read all of our Poetry Month coverage here

Devin Johnston on Christopher Logue’s Iliad