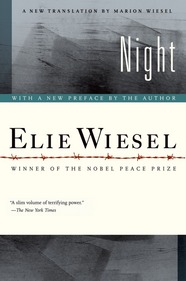

Elie Wiesel was an Auschwitz and Buchenwald survivor who, through his more than fifty books, countless speeches and op-eds, and tireless activism, became a voice for the voiceless. When he won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, they called him “one of the most important spiritual leaders and guides in an age when violence, repression and racism continue to characterise the world.” His death, on July 2, marks the passing of an important writer and humanitarian. His most widely read book, Night, is the account of his time at Auschwitz and Buchenwald as a young man.

opens in a new window |

They called him Moishe the Beadle, as if his entire life he had never had a surname. He was the jack-of-all-trades in a Hasidic house of prayer, a shtibl. The Jews of Sighet—the little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood—were fond of him. He was poor and lived in utter penury. As a rule, our townspeople, while they did help the needy, did not particularly like them. Moishe the Beadle was the exception. He stayed out of people’s way. His presence bothered no one. He had mastered the art of rendering himself insignificant, invisible.

Physically, he was as awkward as a clown. His waiflike shyness made people smile. As for me, I liked his wide, dreamy eyes, gazing off into the distance. He spoke little. He sang, or rather he chanted, and the few snatches I caught here and there spoke of divine suffering, of the Shekhinah in Exile, where, according to Kabbalah, it awaits its redemption linked to that of man.

I met him in 1941. I was almost thirteen and deeply observant. By day I studied Talmud and by night I would run to the synagogue to weep over the destruction of the Temple.

One day I asked my father to find me a master who could guide me in my studies of Kabbalah. “You are too young for that. Maimonides tells us that one must be thirty before venturing into the world of mysticism, a world fraught with peril. First you must study the basic subjects, those you are able to comprehend.”

My father was a cultured man, rather unsentimental. He rarely displayed his feelings, not even within his family, and was more involved with the welfare of others than with that of his own kin. The Jewish community of Sighet held him in highest esteem; his advice on public and even private matters was frequently sought. There were four of us children. Hilda, the eldest; then Bea; I was the third and the only son; Tzipora was the youngest.

My parents ran a store. Hilda and Bea helped with the work. As for me, my place was in the house of study, or so they said.

“There are no Kabbalists in Sighet,” my father would often tell me.

He wanted to drive the idea of studying Kabbalah from my mind. In vain. I succeeded on my own in finding a master for myself in the person of Moishe the Beadle.

He had watched me one day as I prayed at dusk.

“Why do you cry when you pray?” he asked, as though he knew me well.

“I don’t know,” I answered, troubled.

I had never asked myself that question. I cried because . . . because something inside me felt the need to cry. That was all I knew.

“Why do you pray?” he asked after a moment.

Why did I pray? Strange question. Why did I live? Why did I breathe?

“I don’t know,” I told him, even more troubled and ill at ease. “I don’t know.”

From that day on, I saw him often. He explained to me, with great emphasis, that every question possessed a power that was lost in the answer . . .

Man comes closer to God through the questions he asks Him, he liked to say. Therein lies true dialogue. Man asks and God replies. But we don’t understand His replies. We cannot understand them. Because they dwell in the depths of our souls and remain there until we die. The real answers, Eliezer, you will find only within yourself.

“And why do you pray, Moishe?” I asked him.

“I pray to the God within me for the strength to ask Him the real questions.”

We spoke that way almost every evening, remaining in the synagogue long after all the faithful had gone, sitting in the semidarkness where only a few half-burnt candles provided a flickering light. One evening, I told him how unhappy I was not to be able to find in Sighet a master to teach me the Zohar, the Kabbalistic works, the secrets of Jewish mysticism. He smiled indulgently. After a long silence, he said, “There are a thousand and one gates allowing entry into the orchard of mystical truth. Every human being has his own gate. He must not err and wish to enter the orchard through a gate other than his own. That would present a danger not only for the one entering but also for those who are already inside.”

And Moishe the Beadle, the poorest of the poor of Sighet, spoke to me for hours on end about the Kabbalah’s revelations and its mysteries. Thus began my initiation. Together we would read, over and over again, the same page of the Zohar. Not to learn it by heart but to discover within the very essence of divinity.

And in the course of those evenings I became convinced that Moishe the Beadle would help me enter eternity, into that time when question and answer would become ONE.

***

And then, one day all foreign Jews were expelled from Sighet. And Moishe the Beadle was a foreigner.

Crammed into cattle cars by the Hungarian police, they cried silently. Standing on the station platform, we too were crying. The train disappeared over the horizon; all that was left was thick, dirty smoke.

Behind me, someone said, sighing, “What do you expect? That’s war . . . ”

The deportees were quickly forgotten. A few days after they left, it was rumored that they were in Galicia, working, and even that they were content with their fate.

Days went by. Then weeks and months. Life was normal again. A calm, reassuring wind blew through our homes. The shopkeepers were doing good business, the students lived among their books, and the children played in the streets.

One day, as I was about to enter the synagogue, I saw Moishe the Beadle sitting on a bench near the entrance.

He told me what had happened to him and his companions. The train with the deportees had crossed the Hungarian border and, once in Polish territory, had been taken over by the Gestapo. The train had stopped. The Jews were ordered to get off and onto waiting trucks. The trucks headed toward a forest. There everybody was ordered to get out. They were forced to dig huge trenches. When they had finished their work, the men from the Gestapo began theirs. Without passion or haste, they shot their prisoners, who were forced to approach the trench one by one and offer their necks. Infants were tossed into the air and used as targets for the machine guns. This took place in the Galician forest, near Kolo-may. How had he, Moishe the Beadle, been able to escape? By a miracle. He was wounded in the leg and left for dead . . .

Day after day, night after night, he went from one Jewish house to the next, telling his story and that of Malka, the young girl who lay dying for three days, and that of Tobie, the tailor who begged to die before his sons were killed.

Moishe was not the same. The joy in his eyes was gone. He no longer sang. He no longer mentioned either God or Kabbalah. He spoke only of what he had seen. But people not only refused to believe his tales, they refused to listen. Some even insinuated that he only wanted their pity, that he was imagining things. Others flatly said that he had gone mad.

As for Moishe, he wept and pleaded:

“Jews, listen to me! That’s all I ask of you. No money. No pity. Just listen to me!” he kept shouting in synagogue, between the prayer at dusk and the evening prayer.

Even I did not believe him. I often sat with him, after services, and listened to his tales, trying to understand his grief. But all I felt was pity.

“They think I’m mad,” he whispered, and tears, like drops of wax, flowed from his eyes.

Once, I asked him the question: “Why do you want people to believe you so much? In your place I would not care whether they believed me or not . . . ”

He closed his eyes, as if to escape time.

“You don’t understand,” he said in despair. “You cannot understand. I was saved miraculously. I succeeded in coming back. Where did I get my strength? I wanted to return to Sighet to describe to you my death so that you might ready yourselves while there is still time. Life? I no longer care to live. I am alone. But I wanted to come back to warn you. Only no one is listening to

me . . . ”

This was toward the end of 1942.

Thereafter, life seemed normal once again. London radio, which we listened to every evening, announced encouraging news: the daily bombings of Germany and Stalingrad, the preparation of the Second Front. And so we, the Jews of Sighet, waited for better days that surely were soon to come.

I continued to devote myself to my studies, Talmud during the day and Kabbalah at night. My father took care of his business and the community. My grandfather came to spend Rosh Hashanah with us so as to attend the services of the celebrated Rebbe of Borsche. My mother was beginning to think it was high time to find an appropriate match for Hilda.

Thus passed the year 1943.

***

Spring 1944. Splendid news from the Russian Front. There could no longer be any doubt: Germany would be defeated. It was only a matter of time, months or weeks, perhaps.

The trees were in bloom. It was a year like so many others, with its spring, its engagements, its weddings, and its births.

The people were saying,”The Red Army is advancing with giant strides . . . Hitler will not be able to harm us, even if he wants to . . . ”

Yes, we even doubted his resolve to exterminate us.

Annihilate an entire people? Wipe out a population dispersed throughout so many nations? So many millions of people! By what means? In the middle of the twentieth century!

And thus my elders concerned themselves with all manner of things—strategy, diplomacy, politics, and Zionism—but not with their own fate.

Even Moishe the Beadle had fallen silent. He was weary of talking. He would drift through synagogue or through the streets, hunched over, eyes cast down, avoiding people’s gaze.

In those days it was still possible to buy emigration certificates to Palestine. I had asked my father to sell everything, to liquidate everything, and to leave.

“I am too old, my son,” he answered. “Too old to start a new life. Too old to start from scratch in some distant land . . . ”

Budapest radio announced that the Fascist party had seized power. The regent Miklós Horthy was forced to ask a leader of the pro-Nazi Nyilas party to form a new government.

Yet we still were not worried. Of course we had heard of the Fascists, but it was all in the abstract. It meant nothing more to us than a change of ministry.

The next day brought really disquieting news: German troops had penetrated Hungarian territory with the government’s approval.

Finally, people began to worry in earnest. One of my friends, Moishe Chaim Berkowitz, returned from the capital for Passover and told us, “The Jews of Budapest live in an atmosphere of fear and terror. Anti-Semitic acts take place every day, in the streets, on the trains. The Fascists attack Jewish stores, synagogues. The situation is becoming very serious . . . ”

The news spread through Sighet like wildfire. Soon that was all people talked about. But not for long. Optimism soon revived: The Germans will not come this far. They will stay in Budapest. For strategic reasons, for political

reasons . . .

In less than three days, German Army vehicles made their appearance on our streets.

***

Anguish. German soldiers—with their steel helmets and their death’s-head emblem. Still, our first impressions of the Germans were rather reassuring. The officers were billeted in private homes, even in Jewish homes. Their attitude toward their hosts was distant but polite. They never demanded the impossible, made no offensive remarks, and sometimes even smiled at the lady of the house. A German officer lodged in the Kahns’ house across the street from us. We were told he was a charming man, calm, likable, and polite. Three days after he moved in, he brought Mrs. Kahn a box of chocolates. The optimists were jubilant: “Well? What did we tell you? You wouldn’t believe us. There they are, your Germans. What do you say now? Where is their famous cruelty?”

The Germans were already in our town, the Fascists were already in power, the verdict was already out—and the Jews of Sighet were still smiling.

***

The eight days of Passover.

The weather was sublime. My mother was busy in the kitchen. The synagogues were no longer open. People gathered in private homes: no need to provoke the Germans.

Almost every rabbi’s home became a house of prayer.

We drank, we ate, we sang. The Bible commands us to rejoice during the eight days of celebration, but our hearts were not in it. We wished the holiday would end so as not to have to pretend.

On the seventh day of Passover, the curtain finally rose: the Germans arrested the leaders of the Jewish community.

From that moment on, everything happened very quickly. The race toward death had begun.

First edict: Jews were prohibited from leaving their residences for three days, under penalty of death.

Moishe the Beadle came running to our house.

“I warned you,” he shouted. And left without waiting for a response.

The same day, the Hungarian police burst into every Jewish home in town: a Jew was henceforth forbidden to own gold, jewelry, or any valuables. Everything had to be handed over to the authorities, under penalty of death. My father went down to the cellar and buried our savings.

As for my mother, she went on tending to the many chores in the house. Sometimes she would stop and gaze at us in silence.

Three days later, a new decree: every Jew had to wear the yellow star.

Some prominent members of the community came to consult with my father, who had connections at the upper levels of the Hungarian police; they wanted to know what he thought of the situation. My father’s view was that it was not all bleak, or perhaps he just did not want to discourage the others, to throw salt on their wounds:

“The yellow star? So what? It’s not lethal . . . ”

(Poor Father! Of what then did you die?)

But new edicts were already being issued. We no longer had the right to frequent restaurants or cafés, to travel by rail, to attend synagogue, to be on the streets after six o’clock in the evening.

Then came the ghettos.

***

Two ghettos were created in Sighet. A large one in the center of town occupied four streets, and another smaller one extended over several alleyways on the outskirts of town. The street we lived on, Serpent Street, was in the first ghetto. We therefore could remain in our house. But, as it occupied a corner, the windows facing the street outside the ghetto had to be sealed. We gave some of our rooms to relatives who had been driven out of their homes.

Little by little life returned to “normal.” The barbed wire that encircled us like a wall did not fill us with real fear. In fact, we felt this was not a bad thing; we were entirely among ourselves. A small Jewish republic . . . A Jewish Council was appointed, as well as a Jewish police force, a welfare agency, a labor committee, a health agency—a whole governmental apparatus.

People thought this was a good thing. We would no longer have to look at all those hostile faces, endure those hate-filled stares. No more fear. No more anguish. We would live among Jews, among brothers . . .

Of course, there still were unpleasant moments. Every day, the Germans came looking for men to load coal into the military trains. Volunteers for this kind of work were few. But apart from that, the atmosphere was oddly peaceful and reassuring.

Most people thought that we would remain in the ghetto until the end of the war, until the arrival of the Red Army. Afterward everything would be as before. The ghetto was ruled by neither German nor Jew; it was ruled by delusion.

***

Some two weeks before Shavuot. A sunny spring day, people strolled seemingly carefree through the crowded streets. They exchanged cheerful greetings. Children played games, rolling hazelnuts on the sidewalks. Some schoolmates and I were in Ezra Malik’s garden studying a Talmudic treatise.

Night fell. Some twenty people had gathered in our courtyard. My father was sharing some anecdotes and holding forth on his opinion of the situation. He was a good storyteller.

Suddenly, the gate opened, and Stern, a former shopkeeper who now was a policeman, entered and took my father aside. Despite the growing darkness, I could see my father turn pale.

“What’s wrong?” we asked.

“I don’t know. I have been summoned to a special meeting of the Council. Something must have happened.”

The story he had interrupted would remain unfinished.

“I’m going right now,” he said. “I’ll return as soon as possible. I’ll tell you everything. Wait for me.”

We were ready to wait as long as necessary. The courtyard turned into something like an antechamber to an operating room. We stood, waiting for the door to open. Neighbors, hearing the rumors, had joined us. We stared at our watches. Time had slowed down. What was the meaning of such a long session?

“I have a bad feeling,” said my mother. “This afternoon I saw new faces in the ghetto. Two German officers, I believe they were Gestapo. Since we’ve been here, we have not seen a single officer . . . ”

It was close to midnight. Nobody felt like going to sleep, though some people briefly went to check on their homes. Others left but asked to be called as soon as my father returned.

At last, the door opened and he appeared. His face was drained of color. He was quickly surrounded.

“Tell us. Tell us what’s happening! Say something . . . ”

At that moment, we were so anxious to hear something encouraging, a few words telling us that there was nothing to worry about, that the meeting had been routine, just a review of welfare and health problems . . . But one glance at my father’s face left no doubt.

“The news is terrible,” he said at last. And then one word: “Transports.”

The ghetto was to be liquidated entirely. Departures were to take place street by street, starting the next day.

We wanted to know everything, every detail. We were stunned, yet we wanted to fully absorb the bitter news.

“Where will they take us?”

That was a secret. A secret for all, except one: the president of the Jewish Council. But he would not tell, or could not tell. The Gestapo had threatened to shoot him if he talked.

“There are rumors,” my father said, his voice breaking, “that we are being taken somewhere in Hungary to work in the brick factories. It seems that here, we are too close to the front . . . ”

After a moment’s silence, he added:

“Each of us will be allowed to bring his personal belongings. A backpack, some food, a few items of clothing. Nothing else.”

Again, heavy silence.

“Go and wake the neighbors,” said my father. “They must get ready . . . ”

The shadows around me roused themselves as if from a deep sleep and left silently in every direction.

***

For a moment, we remained alone. Suddenly Batia Reich, a relative who lived with us, entered the room: “Someone is knocking at the sealed window, the one that faces outside!”

It was only after the war that I found out who had knocked that night. It was an inspector of the Hungarian police, a friend of my father’s. Before we entered the ghetto, he had told us, “Don’t worry. I’ll warn you if there is danger.” Had he been able to speak to us that night, we might still have been able to flee . . . But by the time we succeeded in opening the window, it was too late. There was nobody outside.

***

The ghetto was awake. One after the other, the lights were going on behind the windows.

I went into the house of one of my father’s friends. I woke the head of the household, a man with a gray beard and the gaze of a dreamer. His back was hunched over from untold nights spent studying.

“Get up, sir, get up! You must ready yourself for the journey. Tomorrow you will be expelled, you and your family, you and all the other Jews. Where to? Please don’t ask me, sir, don’t ask questions. God alone could answer you. For heaven’s sake, get up . . . ”

He had no idea what I was talking about. He probably thought I had lost my mind.

“What are you saying? Get ready for the journey? What journey? Why? What is happening? Have you gone mad?”

Half asleep, he was staring at me, his eyes filled with terror, as though he expected me to burst out laughing and tell him to go back to bed. To sleep. To dream. That nothing had happened. It was all in jest . . .

My throat was dry and the words were choking me, paralyzing my lips. There was nothing else to say.

At last he understood. He got out of bed and began to dress, automatically. Then he went over to the bed where his wife lay sleeping and with infinite tenderness touched her forehead. She opened her eyes and it seemed to me that a smile crossed her lips. Then he went to wake his two children. They woke with a start, torn from their dreams. I fled.

Time went by quickly. It was already four o’clock in the morning. My father was running right and left, exhausted, consoling friends, checking with the Jewish Council just in case the order had been rescinded. To the last moment, people clung to hope.

The women were boiling eggs, roasting meat, preparing cakes, sewing backpacks. The children were wandering about aimlessly, not knowing what to do with themselves to stay out of the way of the grown-ups.

Our backyard looked like a marketplace. Valuable objects, precious rugs, silver candlesticks, Bibles and other ritual objects were strewn over the dusty grounds—pitiful relics that seemed never to have had a home. All this under a magnificent blue sky.

By eight o’clock in the morning, weariness had settled into our veins, our limbs, our brains, like molten lead. I was in the midst of prayer when suddenly there was shouting in the streets. I quickly unwound my phylacteries and ran to the window. Hungarian police had entered the ghetto and were yelling in the street nearby.

“All Jews, outside! Hurry!”

They were followed by Jewish police, who, their voices breaking, told us:

“The time has come . . . you must leave all this . . . ”

The Hungarian police used their rifle butts, their clubs to indiscriminately strike old men and women, children and cripples.

One by one, the houses emptied and the streets filled with people carrying bundles. By ten o’clock, everyone was outside. The police were taking roll calls, once, twice, twenty times. The heat was oppressive. Sweat streamed from people’s faces and bodies.

Children were crying for water.

Water! There was water close by inside the houses, the backyards, but it was forbidden to break rank.

“Water, Mother, I am thirsty!”

Some of the Jewish police surreptitiously went to fill a few jugs. My sisters and I were still allowed to move about, as we were destined for the last convoy, and so we helped as best we could.

***

At last, at one o’clock in the afternoon came the signal to leave.

There was joy, yes, joy. People must have thought there could be no greater torment in God’s hell than that of being stranded here, on the sidewalk, among the bundles, in the middle of the street under a blazing sun. Anything seemed preferable to that. They began to walk without another glance at the abandoned streets, the dead, empty houses, the gardens, the tombstones . . . On everyone’s back, there was a sack. In everyone’s eyes, tears and distress. Slowly, heavily, the procession advanced toward the gate of the ghetto.

And there I was, on the sidewalk, watching them file past, unable to move. Here came the Chief Rabbi, hunched over, his face strange looking without a beard, a bundle on his back. His very presence in the procession was enough to make the scene seem surreal. It was like a page torn from a book, a historical novel, perhaps, dealing with the captivity in Babylon or the Spanish Inquisition.

They passed me by, one after the other, my teachers, my friends, the others, some of whom I had once feared, some of whom I had found ridiculous, all those whose lives I had shared for years. There they went, defeated, their bundles, their lives in tow, having left behind their homes, their childhood.

They passed me by, like beaten dogs, with never a glance in my direction. They must have envied me.

The procession disappeared around the corner. A few steps more and they were beyond the ghetto walls.

The street resembled fairgrounds deserted in haste. There was a little of everything: suitcases, briefcases, bags, knives, dishes, banknotes, papers, faded portraits. All the things one planned to take along and finally left behind. They had ceased to matter.

Open rooms everywhere. Gaping doors and windows looked out into the void. It all belonged to everyone since it no longer belonged to anyone. It was there for the taking. An open tomb.

A summer sun.

***

We had spent the day without food. But we were not really hungry. We were exhausted.

My father had accompanied the deportees as far as the ghetto’s gate. They first had been herded through the main synagogue, where they were thoroughly searched to make sure they were not carrying away gold, silver, or any other valuables. There had been incidents of hysteria and harsh blows.

“When will it be our turn?” I asked my father.

“The day after tomorrow. Unless . . . things work out. A miracle, perhaps . . . ”

Where were the people being taken? Did anyone know yet? No, the secret was well kept.

Night had fallen. That evening, we went to bed early. My father said:

“Sleep peacefully, children. Nothing will happen until the day after tomorrow, Tuesday.”

Monday went by like a small summer cloud, like a dream in the first hours of dawn.

Intent on preparing our backpacks, on baking breads and cakes, we no longer thought about anything. The verdict had been delivered.

That evening, our mother made us go to bed early. To conserve our strength, she said.

It was to be the last night spent in our house.

I was up at dawn. I wanted to have time to pray before leaving.

My father had risen before all of us, to seek information in town. He returned around eight o’clock. Good news: we were not leaving town today; we were only moving to the small ghetto. That is where we were to wait for the last transport. We would be the last to leave.

At nine o’clock, the previous Sunday’s scenes were repeated. Policemen wielding clubs were shouting:

“All Jews outside!”

We were ready. I went out first. I did not want to look at my parents’ faces. I did not want to break into tears. We remained sitting in the middle of the street, like the others two days earlier. The same hellish sun. The same thirst. Only there was no one left to bring us water.

I looked at my house in which I had spent years seeking my God, fasting to hasten the coming of the Messiah, imagining what my life would be like later. Yet I felt little sadness. My mind was empty.

“Get up! Roll call!”

We stood. We were counted. We sat down. We got up again. Over and over. We waited impatiently to be taken away. What were they waiting for? Finally, the order came:

“Forward! March!”

My father was crying. It was the first time I saw him cry. I had never thought it possible. As for my mother, she was walking, her face a mask, without a word, deep in thought. I looked at my little sister, Tzipora, her blond hair neatly combed, her red coat over her arm: a little girl of seven. On her back a bag too heavy for her. She was clenching her teeth; she already knew it was useless to complain. Here and there, the police were lashing out with their clubs: “Faster!” I had no strength left. The journey had just begun and I already felt so weak . . .

“Faster! Faster! Move, you lazy good-for-nothings!” the Hungarian police were screaming.

That was when I began to hate them, and my hatred remains our only link today. They were our first oppressors. They were the first faces of hell and death.

They ordered us to run. We began to run. Who would have thought that we were so strong? From behind their windows, from behind their shutters, our fellow citizens watched as we passed.

We finally arrived at our destination. Throwing down our bundles, we dropped to the ground:

“Oh God, Master of the Universe, in your infinite compassion, have mercy on us . . . ”

***

The small ghetto. Only three days ago, people were living here. People who owned the things we were using now. They had been expelled. And we had already forgotten all about them.

The chaos was even greater here than in the large ghetto. Its inhabitants evidently had been caught by surprise. I visited the rooms that had been occupied by my Uncle Mendel’s family. On the table, a half-finished bowl of soup. A platter of dough waiting to be baked. Everywhere on the floor there were books. Had my uncle meant to take them along?

We settled in. (What a word!) I went looking for wood, my sisters lit a fire. Despite her fatigue, my mother began to prepare a meal.

We cannot give up, we cannot give up, she kept repeating.

People’s morale was not so bad: we were beginning to get used to the situation. There were those who even voiced optimism. The Germans were running out of time to expel us, they argued . . . Tragically for those who had already been deported, it would be too late. As for us, chances were that we would be allowed to go on with our miserable little lives until the end of the war.

The ghetto was not guarded. One could enter and leave as one pleased. Maria, our former maid, came to see us. Sobbing, she begged us to come with her to her village where she had prepared a safe shelter.

My father wouldn’t hear of it. He told me and my big sisters,”If you wish, go there. I shall stay here with your mother and the little one . . . ”

Naturally, we refused to be separated.

***

Night. No one was praying for the night to pass quickly. The stars were but sparks of the immense conflagration that was consuming us. Were this conflagration to be extinguished one day, nothing would be left in the sky but extinct stars and unseeing eyes.

There was nothing else to do but to go to bed, in the beds of those who had moved on. We needed to rest, to gather our strength.

At daybreak, the gloom had lifted. The mood was more confident. There were those who said:

“Who knows, they may be sending us away for our own good. The front is getting closer, we shall soon hear the guns. And then surely the civilian population will be evacuated . . . ”

“They worry lest we join the partisans . . . ”

“As far as I’m concerned, this whole business of deportation is nothing but a big farce. Don’t laugh. They just want to steal our valuables and jewelry. They know that it has all been buried and that they will have to dig to find it; so much easier to do when the owners are on vacation . . . ”

On vacation!

This kind of talk that nobody believed helped pass the time. The few days we spent here went by pleasantly enough, in relative calm. People rather got along. There no longer was any distinction between rich and poor, notables and the others; we were all people condemned to the same fate—still unknown.

***

Saturday, the day of rest, was the day chosen for our expulsion.

The night before, we had sat down to the traditional Friday night meal. We had said the customary blessings over the bread and the wine and swallowed the food in silence. We sensed that we were gathered around the familial table for the last time. I spent that night going over memories and ideas and was unable to fall asleep.

At dawn, we were in the street, ready to leave. This time, there were no Hungarian police. It had been agreed that the Jewish Council would handle everything by itself.

Our convoy headed toward the main synagogue. The town seemed deserted. But behind the shutters, our friends of yesterday were probably waiting for the moment when they could loot our homes.

The synagogue resembled a large railroad station: baggage and tears. The altar was shattered, the wall coverings shredded, the walls themselves bare. There were so many of us, we could hardly breathe. The twenty-four hours we spent there were horrendous. The men were downstairs, the women upstairs. It was Saturday—the Sabbath—and it was as though we were there to attend services. Forbidden to go outside, people relieved themselves in a corner.

The next morning, we walked toward the station, where a convoy of cattle cars was waiting. The Hungarian police made us climb into the cars, eighty persons in each one. They handed us some bread, a few pails of water. They checked the bars on the windows to make sure they would not come loose. The cars were sealed. One person was placed in charge of every car: if someone managed to escape, that person would be shot.

Two Gestapo officers strolled down the length of the platform. They were all smiles; all things considered, it had gone very smoothly.

A prolonged whistle pierced the air. The wheels began to grind. We were on our way.

Elie Wiesel was the author of more than fifty internationally acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States of America Congressional Gold Medal, the French Legion of Honor, and, in 1986, the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and University Professor at Boston University.