Susan Brind Morrow, Robert Thurman, and James A. Kowalski

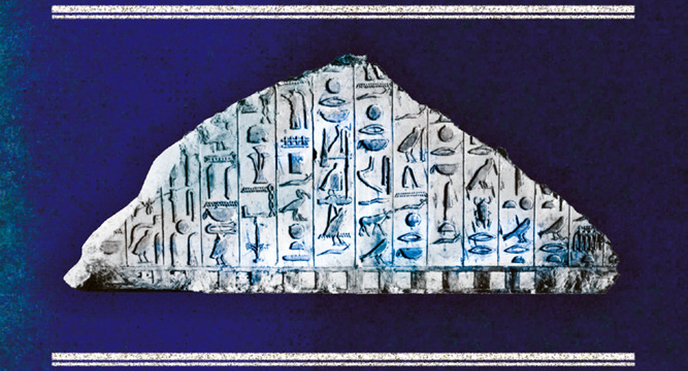

Susan Brind Morrow is the author of a new book, The Dawning Moon of the Mind, in which she details her revolutionary translation of the Pyramid Texts—a series of carvings found in a semi-collapsed pyramid in Egypt, and the basis for a reinterpretation of ancient Egyptian religion. She spoke with Robert Thurman, the Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, and James A. Kowalski, dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, about her new translation, and the natural beauty and poetry of ancient Egyptian texts.

|

Robert Thurman: I’m not the one to respond in a learned manner to this amazing work of scholarship and courageous work revolutionizing the understanding of this ancient and seminal and important document at this tomb, the tomb of Unis. It’s the oldest religious document that we have on the planet, in writing. But, I’m happy to, because I admire it so much. Susan is way too modest when she talks of what she has written here, which is extremely learned and incredibly rich in its understanding, yet very, very poetic. There used to be that Western way of looking at [other civilizations] as strange, backward things. The previous translations of the Pyramid Texts really emphasize that backwardness: “Pull back, Baboon’s penis! Open, sky’s door! You sealed door, open a path for Unis on the blast of heat where the gods scoop water.”

Why are they scooping water? Are they trying to put out the fire? And it goes on like that:

“Horus’ glide path—TWICE!… Unis becomes a screeching howling baboon.”

It’s just incredible!

And then we look at your translation, which fits perfectly with the stars rising in the dawn light. You reveal that this tomb is really celebrating eternal life. Death is commemorated by the dawn, which is considered life coming out of the womb of the night. It celebrates the king’s immortality, that the king returns.

All these guys who were translating this text into gobbledygook—and you just patiently figured it out. I think that the real reason you were able to do so was because of the time you spent in Egypt, absorbing the atmosphere of the desert, empathizing with the people of Egypt in that very delicate situation, dependent on the Nile for their life. You looked at it with a kind of respect that the earlier Egyptologists couldn’t do. Those men couldn’t figure out the beauty, the poetic simplicity, and the profundity of what it was they had encountered. I think that what you’ve accomplished is truly revolutionary. You must have some enemies. Were you frightened when you realized you were overthrowing all these previous interpretations and you found very solid reasoning in the hieroglyphs themselves? Were you a little afraid that the “ancient” authorities would get you?

Susan Brind Morrow: I’d seen the verses in my teens, and I remembered these beautiful individual lines. When you work in antiquities, you are always seeing fragments, pieces of lines that are really stunning. I wanted to go back and look at the whole thing. I assumed that the earlier translations were correct, that the magic spell interpretation was correct. But when I looked at the original it suddenly occurred to me, “My God, it’s Sirius.” And if it’s Sirius, then the thing about the baboon in the beginning is the Sword of Orion, which rises directly before Sirius in the dawn. And the second verse, “Would that the bull break the fingers of the horizon with its horns,” understood in the earlier translations to be a monster—you suddenly realize you’re looking at Taurus, Orion, and Sirius rising in a line at the moment of dawn. There’s this incredible immediacy and vividness to it. You’re looking straight at nature through the medium of beautifully composed poetry. I was just astounded. And as I went deeper into the translation, I began to see more and more of these patterns and references. I worked on this for four years, really without doing anything else. Luckily I had a wonderful editor, Eric Chinski, who was very interested in hieroglyphs and metaphor. I think without him I wouldn’t have really pursued it, but he gave me a contract right at the beginning, before I knew what was there, so I had him to talk to throughout the process. I’d run into his office with ten books and say, “Look at this! Can you believe it?”

So the whole thing was a process of discovery. I had a little closet-sized room with word lists, dictionaries, grammars, everything, and I would go in there in the morning and focus on the translation for hours and hours at a time, going over and over every line and image. I have a notebook for everything. I’ve got several hundred spiral notebooks.

RT: You’ve been studying the background for decades.

SBM: I guess in the sense that I studied at Columbia, first with my Greek professor Roger Bagnall who got me interested in Egypt, in courses in which hieroglyphs were still being taught as literature, at Columbia and The Institute of Fine Arts. He is now the Director of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World over by the Met. Roger set me up working in the Egyptian Department at the Brooklyn Museum, and first sent me to work in Egypt in 1980.

RT: Did he react to the book yet?

SBM: He was persuaded by it and wrote a wonderful blurb. But at first we spent five days going back and forth by e-mail; he asked me countless questions. If you look at the hieroglyphs, the language is classic and simple. But it’s shocking how much has been read into the Pyramid Texts in the magic spell translations, how much distortion there is. In the actual text there’s no violence—but in the translations, simple words are made to seem violent. I was pointing these things out to Roger, and showing him Arabic parallels in vocabulary throughout (making connections with Egypt today).

For me the first layer in the text is poetry, the second is nature. As a naturalist, one of the true delights of working with hieroglyphs is that you are looking at very subtle observations of the natural world. And that desert world is so vivid, that silence in the desert. I was listening to a lecture by one of the professors at Columbia who recently proved Einstein’s theory by discovering gravitational waves in space. He was talking about how you see things differently in the desert, how he was able to make his discoveries by spending time in the Nevada desert. He said you see stars so vividly there, what you see are patterns—which is so much the Egyptian way of thinking. In the desert world, things really are pronounced. I always think of the hare in hieroglyphs. The hare is a large animal that seems to arise suddenly from the ground; it is the color of the desert ground. It is the verb “to be.” The animal itself is motion, being. As though existence is being in motion. It is also the motion of the stars: the stars are racing by. The hare with a star is the word for “hour” in hieroglyphs, and it is also the word for “priest,” because the priest is the watcher of the skies and the stars. The Egyptian priests were creating the model of time we use, the calendrical model of time. They did it by minute observation of the rising of stars, which shifts day by day.

I was very lucky to grow up with the traditional model of poetry we all had in those days. I began school in a one-room schoolhouse with a teacher in her mid-eighties, where we were taught to memorize poetry and stand up and recite it, just as we were taught reading and mathematics. My mother had been partly raised by my great aunt, a Canadian poet who lived in a wilderness retreat called Abbey Dawn. In my family the connection between nature and poetry was very strong. When I was here at Columbia in my teens, the professors that I had, Gaster and Porada and others, were elderly people who knew so much—different languages and traditions—and had been thinking about these things for years, the connection between nature and language, thinking about iconography and what it was all about. They knew these things were questions, that they weren’t understood, and they really wanted to get at it. Then when I went to Egypt and was suddenly out in the desert as a young person. I just loved it and couldn’t come back. I stayed over there for years. In that way I was able to have the raw experience with that world which enabled me to see how people thought. There, words have tremendous meaning. People who cannot read memorize a great deal. They know huge amounts of poetry by heart. Epics were still being recited; people would walk for miles to gather around a poet all night. There was improvisational religious poetry. Poetry was very much a part of life. When I finally came back again to look at the hieroglyphs, I brought all of these associations and experiences to it and was able to see the texts differently.

James A. Kowalski: And you entered the desert alone. You entered a world that was dominantly male, and yet you were embraced. But this wasn’t just luck, certainly. You put yourself in situations that must’ve been highly formative and seem to have served you very well.

SBM: I think I had more freedom as a woman, because I didn’t fit in anywhere. I wasn’t threatening, as a man certainly would have been. Lila Abu-Lughod, who is teaching at Columbia now, went to Egypt as an anthropologist and wrote a book called Veiled Sentiments, which is a wonderful book about women using improvisational poetry in Bedouin society. But she was locked into a certain behavioral code as a woman in a traditional Bedouin family, where of course I wasn’t at all. I was sort of received as a man because I didn’t have a family. People were very protective of me. I was in a tribal context, generally. Once you’re under the protection of people, you can trust them. Nothing is going to happen to you. I’m glad I had that experience.

Susan Brind Morrow studied classics, Arabic, and Egyptology at Columbia University. She has lived and traveled extensively in Egypt and Sudan, working as an archaeologist and as a Guggenheim Foundation fellow studying natural history, language, and the uses of poetry. Her first book, The Names of Things: A Passage in the Egyptian Desert, was a finalist for the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for the Art of the Memoir in 1998. She is also the author of Wolves and Honey: A Hidden History of the Natural World.

Robert Thurman is an American Buddhist writer and academic who has written, edited or translated several books on Tibetan Buddhism. He is the Je Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, holding the first endowed chair in this field of study in the United States. He also is the cofounder and president of the Tibet House New York and is active against the People’s Republic of China’s control of Tibet.

Dr. James A. Kowalski is the dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.