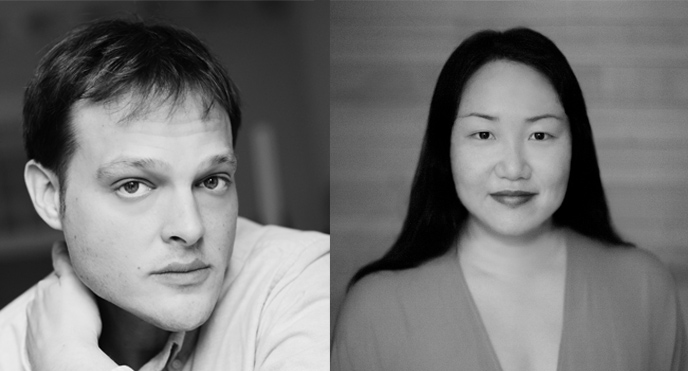

Garth Greenwell (What Belongs to You) and Hanya Yanagihara (A Little Life) have both seen their novels championed (sometimes by one another) as works signalling an exciting new wave of gay literature. But they had never met in person before appearing together at Three Lives Bookstore in Manhattan’s West Village to discuss Garth’s debut novel before a packed crowd. The following is a partial transcription of their conversation.

opens in a new window |

Hanya Yanagihara: One of the things I found interesting about this book are its absences. You never find out the things you’d expect to find out in a book. You never find out why, for example, the narrator is in Sofia. Can you talk to me a little bit about what you chose not to include and how absences to the plot work in this narrative?

Garth Greenwell: Some of the lack of that stuff may just be that I didn’t understand the rules. I didn’t know what you were supposed to put in a book or what you were supposed to explain. The structure of the novel is really weird, and I’m not sure I understood it. I didn’t think I was writing a novel until I had the whole thing done and looked back. I like the idea that juxtaposition can do the work of explanation, and to me those sorts of questions, I don’t know if they’re answered, but the possibility of an answer is in the second section. Also, to me this is a book about a narrator who doesn’t understand himself. I think one of the reasons he can’t offer those explanations is just because he hasn’t formulated them for himself. That’s one of the things he realizes, the extent to which he is a mystery to himself.

HY: Right. You’re a poet. How did you make the transition, are you an accidental novelist? Had you written a lot of prose before you wrote this? I know this emerged from a novella. What was the most complicated part about changing from poetry to prose, into slumming it with the rest of us? [laughter]

GG: That’s funny. [laughs]. I mean I was a poet, well, that’s not true—

HY: You’re in recovery.

GG: I’m in recovery. I’m a recovering poet. But before that, my first introduction to the arts was opera. Singing. So poetry was second. This book begins and ends with Bulgaria, where I went in 2009, and something about being in Bulgaria made me suddenly hear language, sentences, that I somehow knew weren’t broken into lines. I just started writing in a notebook, and in some ways it was much less anxious than writing poetry because I didn’t know anything about writing fiction. I had never studied it. I was really just writing a clause at a time, or a musical phrase at a time, and telling myself—the thing I repeated again and again—be patient and be indulgent and anything that wants to enter this sentence, allow it to enter. Anywhere this sentence wants to go, allow it to go there. I really felt like I was writing into the dark. I had no idea what shape I was writing into, which was very different from how I wrote poetry. I was really overeducated in poetry, you know. I got to study with I think the most exciting poets: Frank Bidart, Carl Phillips, Carolyn Forché, Jorie Graham. These were my teachers, and those are really powerful voices to have in your head. With fiction there was none of that. It was the greatest, the most intensive act of privacy in my whole life. I didn’t show it to anyone; I went years without showing a word to anyone.

HY: How long did you work on it?

GG: I worked on it for about three and a half years. I was teaching high school at the time. Now I think back romantically on this but it was awful: I would wake up at 4:30 in the morning and write for two hours. Most days I taught six hours in the classroom, and at the end of the day I was just dead. So I would write in the morning in the dark in this Soviet apartment building in Mladost, a part of Sofia. It was really, really private. So it’s surreal to have this writing in the world.

HY: Is it lonelier writing fiction, do you think, than writing poetry?

GG: For me it is, because I’m less well-versed in the tradition of fiction, and also because—though there are people who do this—I don’t memorize fiction. I memorize poems. So when I write a poem, when I wrote poems—I haven’t written any in years—every word had a lineage or an echo, like I was talking to Larkin, or I was talking to Bishop. Fiction is a quieter space for me.

HY: Did being in another country where you didn’t have a firm grasp of the language make you rethink English and how you used it?

GG: Absolutely. The thing that interests me as a writer is trying to put consciousness on the page. One particular kind or space of consciousness that I love is that space of being between languages. That sort of constant transaction between one language and another when you’re speaking in a language that you don’t speak very well. That constant slippage, and the way in which your experience is then structured by the language that’s available to it. I think in some ways the whole relationship between the narrator and this man he meets in a public bathroom in Sofia is structured by the word the man gives their relationship, which is this word “priyatel” in Bulgarian. It’s a word that is used both for friend and for boyfriend. It’s very confusing. And also it’s the word that the young man uses for the men who pay him for sex. And it’s like that’s the space of their relationship, it’s really the word that charted it.

HY: I mean one of the things I loved about the book is that Mitko, the object of desire, is named, and the narrator isn’t. It’s an interesting reversal of similar narratives where you have a wealthy Westerner in a country that’s not rich. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

GG: It certainly became a conscious decision. It was something I had to think hard about when I was looking back at the book and actually thinking about some of the choices that I made without thinking about them. It felt right to me. In the first scene the narrator goes to a real place in Sofia, a very famous cruising place, these bathrooms beneath the National Palace of Culture. They’re very far beneath street level, you have to go down and down, and so there’s this kind of literal descent into these bathrooms. When the narrator meets Mitko, we discover that Mitko can’t pronounce the narrator’s name, that his name is unpronounceable in the language. That seemed right, that the narrator is stripped of his name. There’s something almost initiatory about that. But then every character in the book is identified by an initial—except Mitko. Mitko is the one person in the book who has a full name. A name is an investment, that’s why it means something to us when someone remembers our name. Mitko’s name allows the reader to invest in the character, I hope, in a way that foregrounds him. I wanted Mitko to be the most vivid presence on the page. It’s a kind of privilege to have that visibility, to be in a spotlight, but then also like a spotlight it’s a position of vulnerability. That to me felt true to the position Mitko occupies in the narrator’s life and in the world.

HY: I think you’re very right. One of the things I found most moving and disquieting about the book was that although both the narrator and Mitko are in these sorts of liminal states and betwixt and between in so many different ways—job, location, being, adulthood, sex—you know that the narrator has an out and Mitko doesn’t. In a sense, there is no real danger for the narrator.

GG: That’s what being an American means.

HY: Right. It is.

GG: I never understood what it meant to be an American until I was in this place, teaching at an extraordinary school called the American College of Sofia, which is the premier high school in the country. Students come from all over the country and take an exam to get into this school, because the school is their way out. Bulgaria has the greatest demographic crisis in the EU. In 1989, right at the fall of communism, there were more than nine million people in Bulgaria; now there are fewer than seven million. The reason is that everyone leaves. I spent four years teaching the most brilliant students I’ve ever had anywhere, and all of them, almost without exception, left. Almost none of them will go back. It is very hard to live there. Yes, the privilege the narrator has, and the greatest distance between him and Mitko, comes from the fact that he can leave. I think he discovers the limits of his own empathy. He discovers his own ethical limits when he discovers the extent to which he will, and the extent to which he won’t, bind himself, his destiny, to this man and to this place.

HY: I think one of the most wonderful things about this book—I referred to the second section which is really a show stopper—but every now and again the narrative breaks and you move away from the immediate realm of the narrator and Mitko, either into the narrator’s past or into present tense minutely observed. There is a wonderful set piece set on a train in which the narrator is left alone with himself. It’s just completely devastating. As a writer I read it and I thought that it was either the most glorious thing to write—it almost feels like one long breath—or it was something that required a torturous process to make so fluid.

GG: It was hell to write. That second section was awful. I’ve said this before, but I had no idea I was going to write it. With the first section I thought the book was done, I thought the story was closed, I thought maybe I’d write poems again. I was walking around on a hot day, like the narrator in the frame of that section, in Mladost, in this very particular post-socialist landscape. And I felt myself seized by this voice that was full of rage. I started trying to notate that voice. I remember I went to a cafe in Mladost and I wrote it on receipts and napkins—it was like I had to write it on trash. When I finished it, I had to put it away. I couldn’t look at it for a year, it made me sick. It made me physically sick. It was the hardest part of the book to try to get right—and I didn’t get it very right. I rewrote it by hand many times, which I didn’t do for any of the other sections, and each time I tried . . . it was like it was there but I had to clear out the brambles. I did what I could, and then the great good fortune this book had was to find the right editor. That editor was Mitzi Angel, who went over the book with the most extraordinary care. Together we cut. That section went from being maybe fifty-eight pages to forty-one pages of manuscript. She was really the one who, at every point in a sentence, would say, “Is this strong enough?” She was putting pressure everywhere and locating the weak spots and saying, “Make it better.” Mitzi understood what this book should be, which editors don’t always do.

HY: Did she understand it better than you?

GG: Yeah, I think she did. I mean, I think she saw where it was best, she saw better than I did where the sentences were truest. When she cut she was almost always right. I got the manuscript and there were pages that were just x-ed out. I remember it felt very dramatic. Now I look back and I wonder why it seemed so dramatic, but it was dramatic! I read an interview that you did where you said your edits felt “assaultive.” That’s exactly what it felt like, but now I think, thank God! Thank God she did that.

HY: You’re so gracious, Garth! I hope no one from my publisher is here. [laughter] I was recently talking to Ravi, the British editor we both know, and we were talking about what gay literature is and how the twin poles of gay literature have been shame and longing. He was saying that, as young people are more loved these days and grow up with less inherent shame, he wondered what will become of gay fiction. Will gay literature, as we know it, change or will it necessitate a point in which it doesn’t exist? Do you have any feelings about what defines modern gay fiction, and how you think it might develop as politics and sociologies change?

GG: We’re in such a weird moment and such an extraordinary moment for queer people in this country, in certain parts of this country, in certain parts of certain cities in this country, in certain races and in certain demographics. That’s the thing. There’s this air of triumph that’s taken over the story of lesbian and gay people here. To some extent, yes, it’s extraordinary what’s been accomplished. I’m so glad that new possibilities have been opened up for queer people, but they’ve come at a great cost, and they have been delivered only to very slim parts of the population. So I don’t think it’s true that gay kids growing up today—and I feel like I can speak with some authority as I was a high-school teacher for seven years—I don’t think it’s true that gay kids are growing up free of queer shame. I don’t think that’s true. I hope it’s true that there’s more of a possibility that they’re encountering narratives that work against that shame. This book came from the experience I had in Bulgaria of feeling that I was in a place that was both really foreign and really familiar, and of being reminded again and again of growing up gay in Kentucky in the early ’90s. But the big difference was that when I was sixteen, I found Giovanni’s Room and A Boy’s Own Story. Everything in my life had taught me that my life had no meaning, that my life had no value. Those books taught a different lesson; those books said that queer lives have value. But it was a tragic value. I do think, when today I read a book like Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, my God, if I had read that book when I was sixteen, it would have changed my life. A book in which queer lives have a value that’s a comic value, that’s a value of happiness—that’s astonishing. Will gay literature disappear? I don’t think so, because what is a tradition? A tradition is just a conversation writers have with each other. To me there is no question of this incredibly exciting, vibrant conversation going on between Proust and Edmund White, and going on between James Baldwin and Alexander Chee and Virginia Woolf, and that’s a conversation that I want to be a part of. I don’t think you’re part of the conversation because you happen to be a man attracted to other men. I mean, I think these are elective affinities. I don’t think they will go away, and I hope that the range of stories queer people can tell about their lives will expand. That’s what I hope, and I think of what an incredibly exciting time it is to be a queer writer. What an astonishing debt we have that can never be repaid to the writers that came before us. There’s this amazing review of What Belongs to You that Aaron Hamburger wrote, and the frame he used was that horrifying New Yorker review John Updike wrote about Alan Hollinghurst in 1999, in which he said gay lives aren’t interesting and gay literature isn’t interesting, because nothing is at stake because they don’t have kids and all they care about is self-gratification. I remember reading that Updike piece when I was at Purchase College, SUNY, and I had just stopped being an opera singer to become a poet. (My parents were thrilled.) I remember reading that piece and thinking, “My God!” In the pages of The New Yorker, homophobia can still just wave its flag, and this bigoted asshole can say about a writer, who in my opinion is much finer than he, that this writer is not worthy of his attention, and he had the whole weight of the literary establishment behind him—in 1999. Unbelievable! But it’s because of Alan Hollinghurst, and Edmund White, and James Baldwin, and Sam Steward, it’s because of these writers that there is a space in which my book can have a different destiny, in which gay books can have different kinds of lives.

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, he holds graduate degrees from Harvard University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was an Arts Fellow. His short fiction has appeared in The Paris Review and A Public Space. What Belongs to You is his first novel.

Hanya Yanagihara is the author of A Little Life and The People in the Trees. She lives in New York City.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

An Excerpt from Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You

Writing From a Distance, by Christobel Kent

On Lucia Berlin: The World in Perpetual Motion

Jonathan Franzen’s First Words on Purity