In 1947, concerned about supporting his family, Kurt Vonnegut took a job his brother recommended him for in the PR department at General Electric. The GE News Bureau was organized like a real newspaper—except that its purpose was to produce stories about all the fabulous inventions and time-saving new products GE was producing.

Kurt had always admired his older brother, Bernard, an MIT-trained chemist. Bernard was working in GE’s pioneering industrial research laboratory, nicknamed “The House of Magic.” Shortly before Kurt arrived, he had begun to work on a fantastic new research project: weather control.

opens in a new window

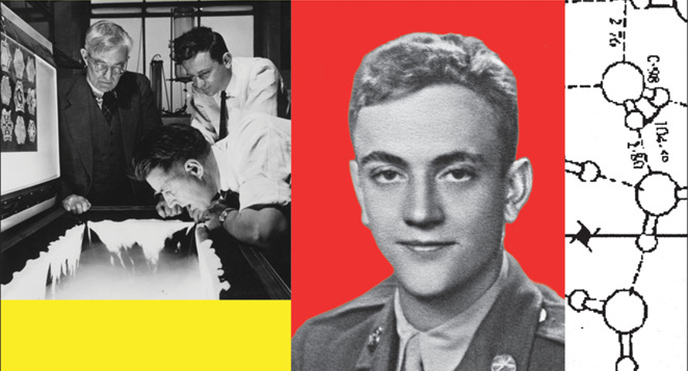

Bernard Vonnegut, center, making rain in a laboratory freezer

One of his colleagues had discovered that dry ice could make the water vapor in clouds condense into raindrops and fall. Bernard soon discovered an even better chemical for seeding clouds: silver iodide. The scientists conducted test flights in which they bombarded clouds with dry ice and silver iodide, producing rain and snow. When GE issued a press release announcing that its scientists had manufactured a snowstorm, the world reacted with jubilation. Newspapers and magazines declared the dawning of a new era: humans were taking control of the weather at last.

One group of people was especially excited: the military. As one general told newspapers, “The nation that first learns to plot the paths of air masses will dominate the globe.” Before long, GE had brought in the Army to take over the weather control project. “Project Cirrus,” as it was now named, was given military planes and pilots. Bernard soon found himself aboard the very same planes that had fire-bombed his brother in Dresden. He realized to his dismay that the military saw his life-giving new invention as a super-weapon.

opens in a new window

Bernard Vonnegut seeds clouds from a bomber plane

Meanwhile, his little brother, Kurt, was spending every day at GE writing press releases and features about the fabulous new world that science and technology were creating. But at night and on weekends, he was following his secret ambition to write, cranking out romances and adventure stories for popular magazines. His only reward was a huge stack of rejection slips.

One day, Kurt had an idea for a new kind of story. He would write about what he was seeing at GE. He would show a scientist facing same ethical dilemma Bernard faced: how responsible was he, as a scientist, for preventing the weaponizing of his inventions? Kurt’s first successful story, “Report on the Barnhouse Effect” sold to Colliers in late 1949.

opens in a new window

Collier’s cover on weather control and illustration from “Barnhouse”

Like Bernard, Professor Barnhouse discovers he can control things previously thought uncontrollable. But his dream of using his power for humanity’s benefit crumbles as he is taken up by military men who only see his invention as a super-weapon. Declaring that “He who rules the Barnhouse Effect rules the world,” the military creates a program with the code-name “Project Wishing Well.” Barnhouse must figure out how to prevent his invention from becoming a weapon.

Kurt had found a successful formula: amp up the scientific and technological advances he was seeing at GE to emphasize their ethical implications. For instance, GE was the first corporation to own a “differential analyzer,” or what we would now call a computer. It was called OMIBAC. Kurt wrote a story called EPICAC, about a computer that falls in love with its programmer’s object of affection.

opens in a new window

GE’s OMIBAC and Vonnegut’s EPICAC

Kurt wrote a press release about ultrasonics—the use of high frequency sound waves in industry, medicine, and research. Then he wrote “The Euphio Question,” about the invention of a sound wave that, played over the radio, causes everyone to quit whatever they are doing and bliss out. Again, he probes the moral issues raised by a new technology.

In fact, GE’s archives hold many of the source materials for early Kurt Vonnegut stories—the deer that got into the factory, the metallurgist who loved model trains, the walking, talking refrigerator that sold appliances, the visit to GE of the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan, destined to be fictionalized as the Shah of Bratpuhr in Player Piano. Asked years later why he had chosen to write science fiction in his early days, Kurt replied “There was no avoiding it, since the General Electric Company WAS science fiction.”

opens in a new window

Bernard Vonnegut lights his silver iodide burner to make rain from fire

But the most significant idea he found there was ice-9. Kurt completed a very early draft of Cat’s Cradle, titled “Ice-9,” while at GE. The way ice-9 is described is exactly how Bernie explained his own invention to Kurt. And in Cat’s Cradle, as in most of his early fiction, Kurt explored the question his own brother faced during those years: the ethical responsibility of the scientist in the new atomic age—an age in which science had become the world’s most effective weapon.

Ginger Strand is the author of three previous books, including Killer on the Road: Violence and the American Interstate. She has written for a wide variety of publications, including Harper’s Magazine, This Land, The Believer, Tin House, The New York Times, and Orion, where she is a contributing editor.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

The Other Side of the Wall by Sloane Crosley

The Writer’s Privileged Addiction: Retaining the Craft by Ceridwen Dovey

An Excerpt of Luc Sante’s The Other Paris