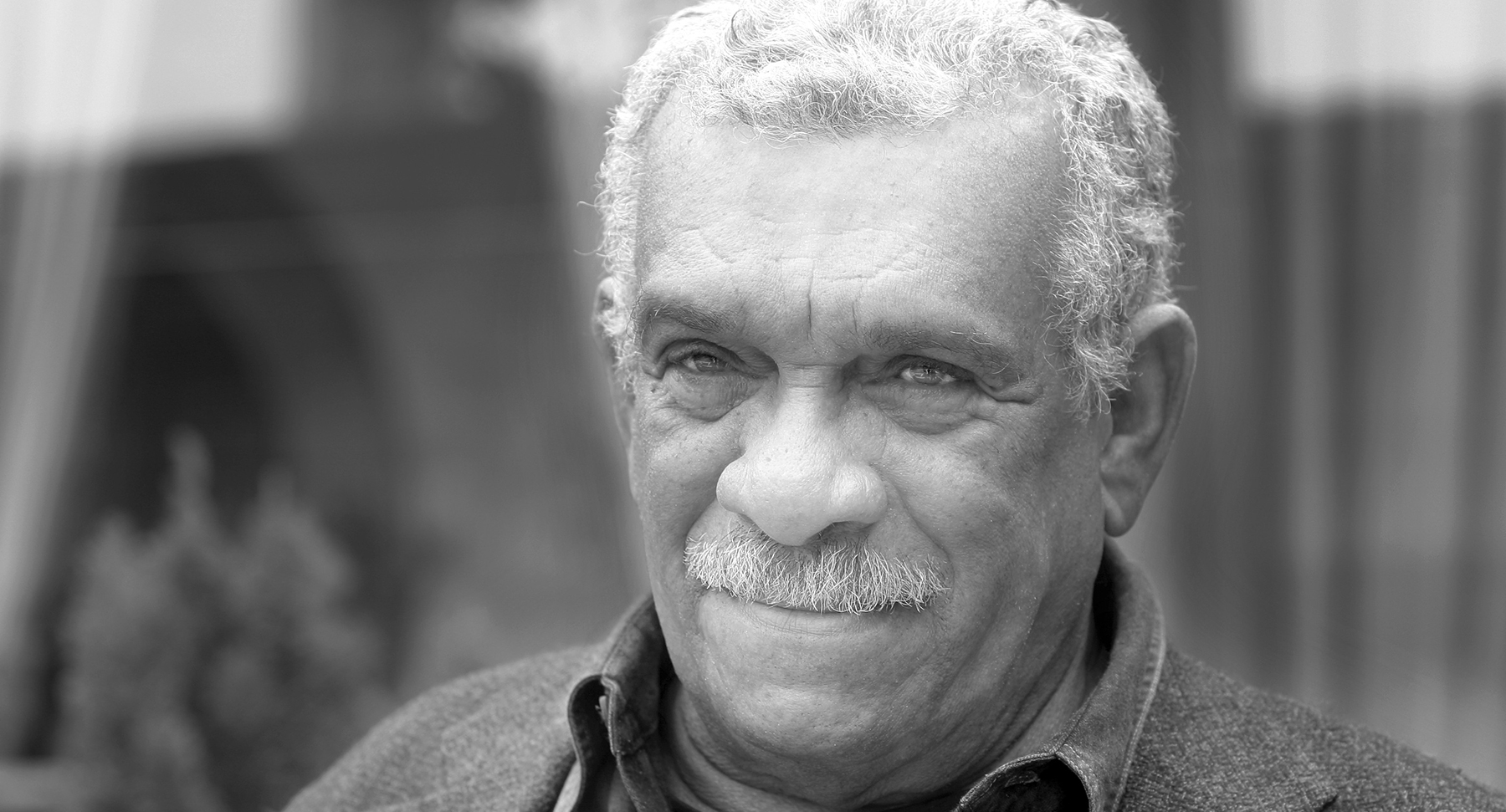

I first met Derek when I came to FSG in the mid-eighties, thirty years ago. He was in his vigorous fifties, teaching in Boston and writing the poems that would soon appear in The Arkansas Testament (1987), and, though I didn’t know it then, composing his magnum opus, Omeros, which we published in 1990.

Derek was a large, deep-voiced, imposing man who mostly kept his own counsel, but I noticed that unlike some he really engaged with his interlocutors. He would have heated, good-natured arguments, about politics and sex and poetic form, that were often saved by a winning and generous sense of humor. I remember him exploding with laughter over one reviewer’s discussion of “The Arkansas Treatment.”

Joseph Brodsky, Seamus Heaney, and Derek made up a triumvirate that defined the second major (i.e., the post–Lowell-Berryman-Jarrell-Bishop) generation of FSG poets. All three would soon win the Nobel Prize in Literature: Brodsky in 1987, Walcott in 1992, and Heaney in 1995. What made them a threesome was a genuine camaraderie, a personal affection, and loyalty, which arose from a shared aesthetic. It’s on display in their brilliant Homage to Robert Frost, which some consider the greatest critical appreciation of Frost there is, for all three were not only great poets but great prose writers, too. These three prodigious outlanders challenged American poetry with vigorous appreciation and a lasting impact.

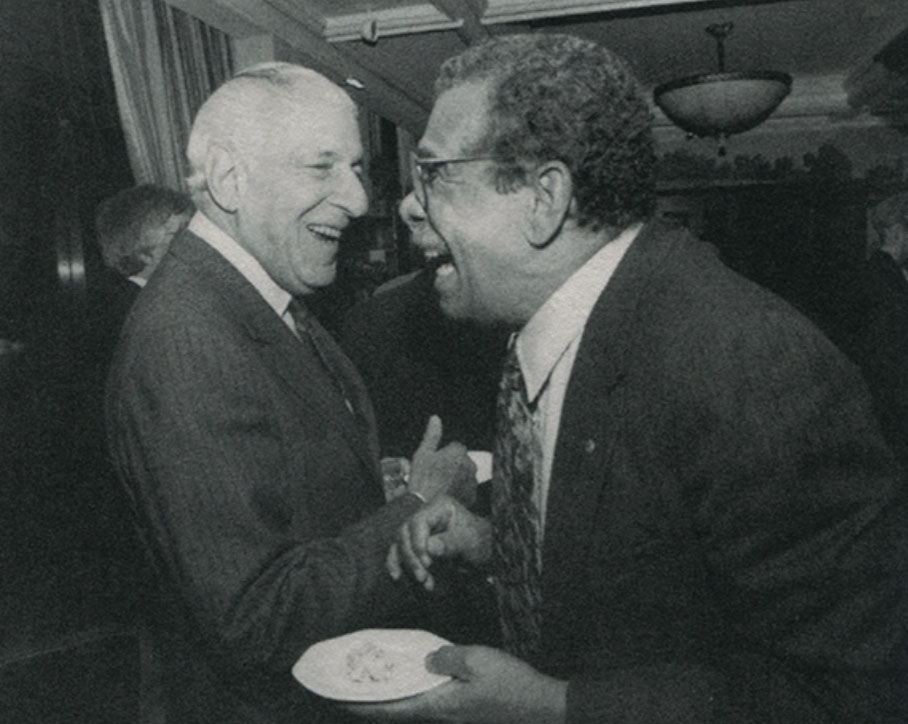

As FSG’s poetry editor, I was lucky to share in lunches of martinis and oysters at the Union Square Cafe, where one or two—and very occasionally all three—of the triumvirate, with their significant others, would come to laugh and gossip with Roger Straus and Peggy Miller. Occasionally we were joined by Paul Simon, who was as starstruck as any of us and was eager to work with Derek on what eventually became the ill-fated Capeman (1998).

ROGER STRAUS AND DEREK WALCOTT AT FSG’S 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION, 1995 (PHOTOGRAPH BY NANCY CRAMPTON)

LUNCH AT THE UNION SQUARE CAFE, MID-1990S (PHOTOGRAPH BY SIGRID NAMA)

This was before Derek and his longtime partner, Sigrid Nama, had their apartment in the Archive in the West Village, where their next-door neighbor was Monica Lewinski. It was before Derek’s fateful first encounter with Italy, too, which inspired Tiepolo’s Hound (2000).

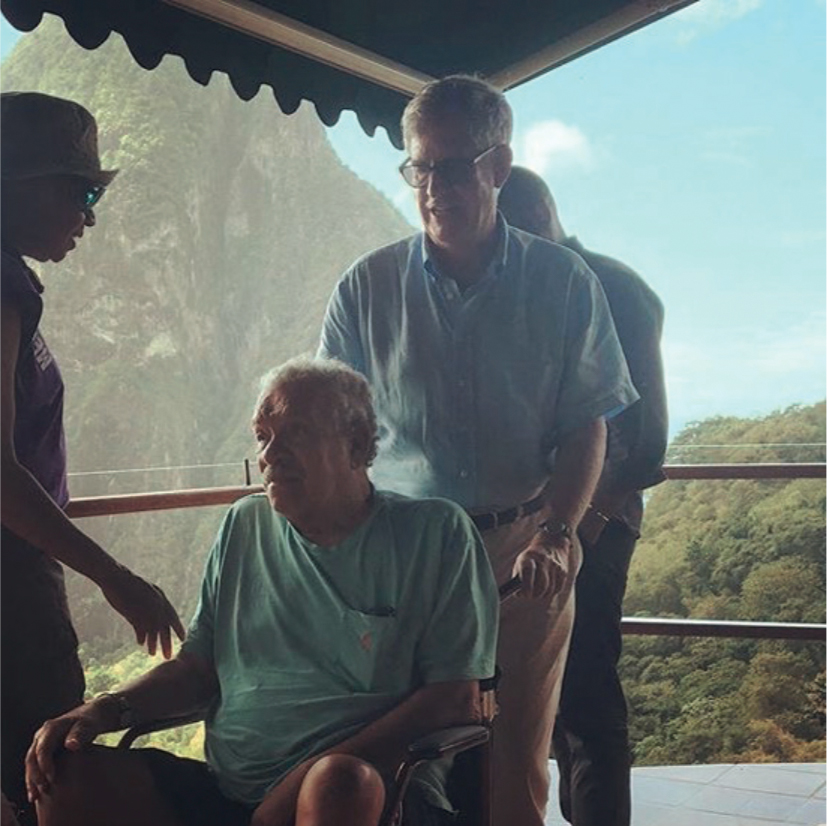

After he stopped teaching in Boston, he and Sigrid started spending more time in Saint Lucia. For his birthday, on January 23, they assembled an ever-growing group that included Derek’s children, Peter, Anna, and Lizzie, and friends from all over the world, with Seamus and Marie Heaney as guests of honor. There were lunches on the beach at Rodney Bay and Cas en Bas, raucous dinners at the Rodney Bay Marina and at Derek and Sigrid’s wonderful house overlooking Pigeon Island, and, on the day itself, a catamaran ride with many of the Walcotts’ local friends down the west side of the island to a sumptuous banquet at the Ladera resort overlooking the Pitons.

LUNCH AT RODNEY BAY, SAINT LUCIA 2014 (PHOTOGRAPH BY TENOCH ESPARZA)

DEREK’S STUDIO (PHOTOGRAPH BY TENOCH ESPARZA)

Derek was always working: on poems, on plays—theater was a life-long preoccupation, from his early days in Trinidad—and on the paintings that brought his world alive in another dimension, and which grace the jackets of most of his books. In his last years he wrote his late masterpiece, White Egrets—though I failed to convince him to do a painting for the jacket this time—and the poems of Morning, Paramin, inspired by the paintings of Peter Doig and published just a few months ago.

I remember how thrilling it was when I fi rst visited Derek in Saint Lucia to understand that the mythic names that studded his poems—Anse La Raye, Gros Islet, Soufrière—belonged to real places we actually visited. The fl ora of Saint Lucia, too—sea grapes, frangipani, dasheen—are vividly evoked, on the page and on the canvas. And seeing Derek’s bust in Derek Walcott Square in the heart of Castries, the capital, I understood in a new way how his is the foundational literature of his nation— its Odyssey, its “Song of Myself ”—and that Derek is his country’s national poet, which means its creator, in a way that is given to only a very few writers.

The specificity of his poetry is only one of its many glories, as is its unblindered understanding of the Caribbean predicament.

Its sound is another. As he put it, “I come from a place

that likes grandeur.” And he was able to make use of the

resources of English with unfettered mastery.

Almost any of his lines is a miracle of sonorous balance.

Here are a just few examples:

My country heart, I am not home till Sesenne sings.

The classics can console. But not enough.

There is too much nothing here.

When he left the beach the sea was still going on.

Again and again in Derek’s work, nature is described as a

book, as a text to be read; by extension, he is arguing that

his work is a part of nature, too. I can think of no other

contemporary writer of whom this is more true.

Derek was a man of prodigious gifts, of deep attachments,

deep loyalties, great pride, and deep humility. He was

such a large presence that he seemed immutable, permanent,

while he was with us. Now that he is gone, we feel

his enduring presence in an entirely new way.

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: JAMAICA KINCAID, DEREK WALCOTT, AND JONATHAN GALASSI AT LADERA, JANUARY 23, 2016 (PHOTOGRAPH BY JULIAN LUCAS)

“Forty Acres” by Derek Walcott

Out of the turmoil emerges one emblem, an engraving —

a young Negro at dawn in straw hat and overalls,

an emblem of impossible prophecy, a crowd

dividing like the furrow which a mule has ploughed,

parting for their president: a field of snow-flecked

cotton

forty acres wide, of crows with predictable omens

that the young ploughman ignores for his unforgotten

cotton-haired ancestors, while lined on one branch, is

a tense

court of bespectacled owls and, on the field’s

receding rim —

a gesticulating scarecrow stamping with rage at him.

The small plough continues on this lined page

beyond the moaning ground, the lynching tree, the tornado’s

black vengeance,

and the young ploughman feels the change in his veins,

heart, muscles, tendons,

till the land lies open like a flag as dawn’s sure

light streaks the field and furrows wait for the sower.

Derek Walcott (1930-2017) was born in St. Lucia, the West Indies, in 1930. His Collected Poems: 1948-1984 was published in 1986, and his subsequent works include a book-length poem, Omeros (1990); a collection of verse, The Bounty (1997); and, in an edition illustrated with his own paintings, the long poem Tiepolo’s Hound (2000). His numerous plays include The Haitian Trilogy (2001) and Walker and The Ghost Dance (2002). Walcott received the Queen’s Medal for Poetry in 1988 and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992.

Jonathan Galassi is the president and publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.