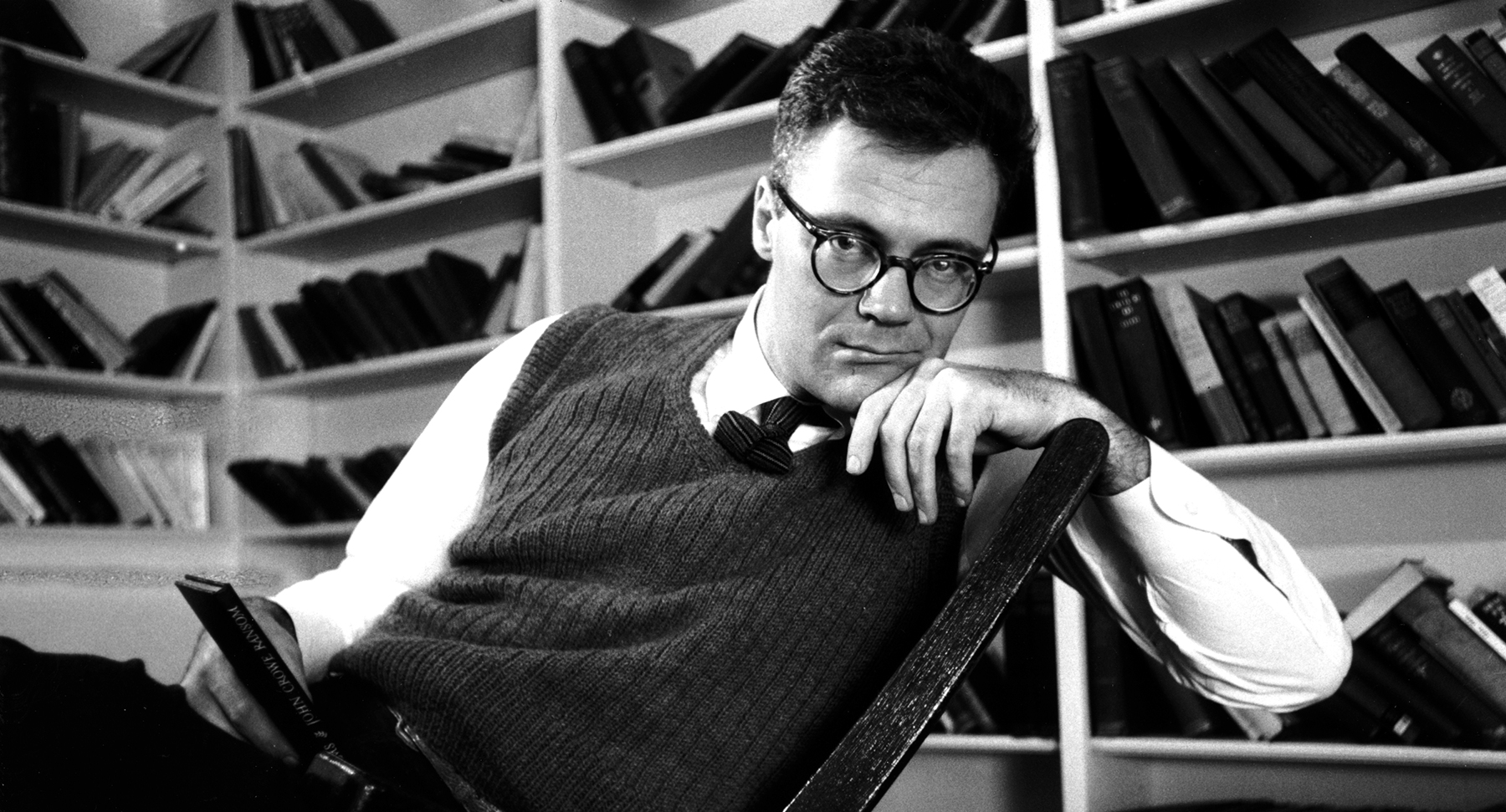

My first experience with Robert Lowell’s poetry was a failure in reading comprehension. Breezing through a stack of poems I’d been assigned for a college class, I came to his “Man and Wife” and gave it my cursory attention. Its setup is not hard...

-

-

by Douglas Smith It was the winter of 2005 and I had been invited to dinner at the Connecticut home of Nikita and Maïko Cheremeteff. I was writing a book on one of Nikita’s ancestors, an eccentric aristocrat from the reign of Catherine the Great who had fallen in love with and secretly married one of his serfs, a brilliant opera singer who performed as “The Pearl.” We talked for hours about Russia, its beauties and tragedies, and about the fabled history of the Counts Sheremetev (as the surname is most commonly anglicized), one of the richest families under the tsars with palaces in St. Petersburg and Moscow, vast estates, and over 300,000 serfs. And then, in 1917, came the revolution. Within a few months the Sheremetevs, like the rest of the nobility, lost everything. Some in the family were arrested and executed, many, like Nikita’s father, fled the country with nothing more than what they could carry. At one point during dinner, Nikita held up piece of silverware, something vaguely resembling a small pâté knife. “Douglas,” he said with a slight grin, “this is all that remains of the Sheremetev fortune.” I felt something click in my head. I had the subject of my next book: the final days of the Russian aristocracy.

-

Earlier this month, FSG published two books on twentieth-century American political figures: William H. Chafe’s Bill and Hillary: The Politics of the Personal and Joseph Crespino’s Strom Thurmond’s America. Neither one is a straightforward biography. Bill and Hillary, which tracks the Clintons’ lives but is focused on the dynamic of their relationship, almost resists classification. Meanwhile, Strom Thurmond’s America is a political biography that out of necessity highlights its subject’s greatest personal failure. We asked the authors to read each other’s book and then discuss, over email, the art of biography. Joe Crespino: One of the things that struck me in reading your book, Bill, was the challenge of writing about people who are so articulate and skilled about shaping their own personal and political narratives. And it’s not only that the Clintons are articulate; they are baby boomers who came of age in a culture of self-exploration and therapeutic analysis. Bill Clinton’s explanations of his own actions and motivations are often self-serving and full of rationalizations, but they are never uninteresting, and in many cases, hold genuine insights. Bill Chafe: Both Bill and Hillary were very self-conscious. They thought a lot about their choices in life. And, of course, both wrote memoirs. Bill, in particular, devotes the first sixty pages or so of his book My Life to his insight into his “parallel lives,” the “secrets” that underlay so much of his troubled journey. He goes to great lengths to get us to accept his rationalizations. But that generates suspicion. What has he not told us? And how does someone writing a biography get at the other side? Both Bill and Hillary—Bill especially—rarely shared the most personal and important sides of their lives. Hillary spoke of growing up in a household that was like “Life with Father,” even though her father, in reality, was a very difficult figure. And through all the years of trauma Bill experienced with a stepfather who was both alcoholic and abusive, he never told his closest friends anything about what he was going through. At Georgetown, he went steady for three years with a woman named Denise Hyland, and in his memoir talks constantly about how they sat on the steps of the Capitol talking all night long about their past and what they planned to do in the future. He even brought her home to meet his folks. But at no point did he ever mention to her the most central reality of his childhood, or how he had to physically intervene to stop his father from beating his mother.