Featuring breathtaking panoramas and revelatory, unforgettable images, Battle Lines is an utterly original graphic history of the Civil War. A collaboration between the award-winning historian Ari Kelman and the acclaimed graphic novelist Jonathan Fetter-Vorm, Battle Lines showcases various objects from the conflict (a tattered American flag from Fort Sumter, a pair of opera glasses, a bullet, an inkwell, and more), along with a cast of soldiers, farmers, slaves, and well-known figures, to trace an ambitious narrative that extends from the early rumblings of secession to the dark years of Reconstruction. Here Ari Kelman and Jonathan Fetter-Vorm talk graphic novels, Civil War reenacting, and drawing like Martin Scorsese.

|

Amanda Moon: Each chapter of Battle Lines starts with an object, and uses that object to tell a larger story about the War. Tell us more about the structure of Battle Lines and how the various objects of the Civil War that are depicted here serve as narrative devices.

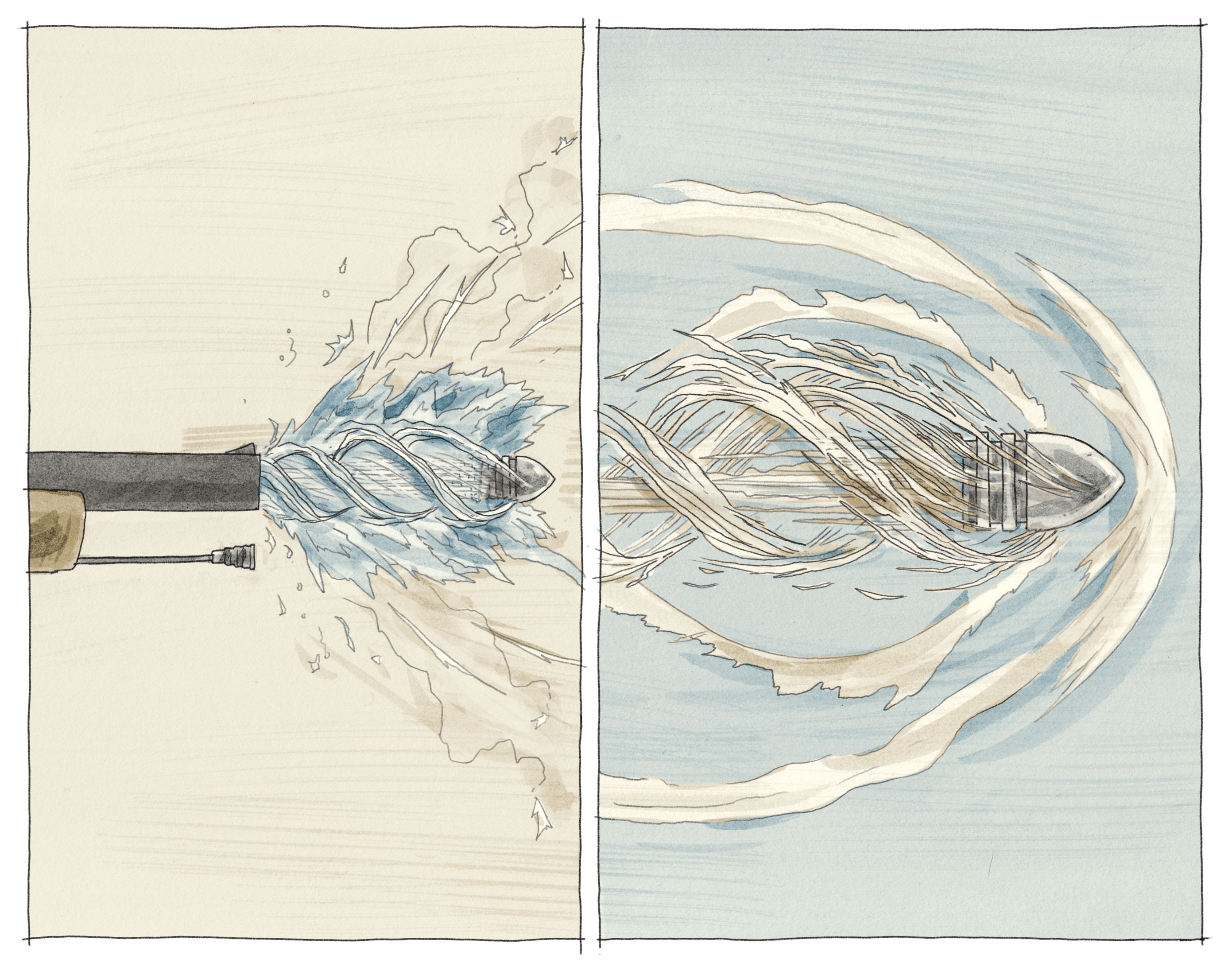

Ari and Jonathan: Two of the challenges we grappled with in writing the book was how to recount the epic history of the Civil War in very few words and also how to provide a fresh perspective on stories that are, because of the number of books published since 1865 about the conflict, rather well known. It seemed to us that one way to accomplish both of these goals was by placing an object—a pair of opera glasses through which spectators observed First Bull Run, a shackle hobbling a slave wandering the Virginia countryside, a bullet shattering the arm of a soldier at Antietam, and many others—at the center of the narrative. These objects provide visual metaphors that serve as a shorthand for readers and also offer new ways of thinking about the Civil War’s history.

Amanda: How did the script turn into the beautiful book we see today? How many stages did you work through before you reached the final round?

Jonathan: We started with Ari’s outline of what historical or thematic aspect each chapter would be about, and from there I drafted a document that looks vaguely like a movie script. This script goes panel by panel through the book, describing what’s going on in the artwork, what’s being said by characters, and what language is appearing in caption boxes. This is also where I include notes to myself about inspiration or mood or source material, so that when it’s time to draw any given page I can look to my script to see notes like, “This should look like a Martin Scorsese movie” or “Draw this like a Two-Fisted Tales comic.”

The editorial process for comics is front-loaded. You have to do all your back-and-forthing at the outset, before it’s time to start drawing, because once you have artwork in place it’s a lot harder to move things around or change the text. To compensate for this, I did some really loose sketches of each page to accompany the script, so that Ari could get a rough idea of how I was thinking of framing each chapter. Of course there were a ton of last minute changes too—little tweaks here and there—but in terms of deep structural decisions, Ari and I tried to get those figured out in the script phase.

Like any book, the progress from outline to the printed page is incremental, and graphic books are no exception. One of the things that I really enjoy about working in this medium is how much reiteration there is: every panel, every page is penciled, then inked, then shaded, then colored, then lettered. By the end of the process I’ve had a chance to go over every detail several times. Though I guess that’s a blessing and a curse. I’m constantly trying to find ways to keep the work feeling fresh and raw, even if, behind the scenes, it’s anything but.

Amanda: Tell us a bit about your collaboration—the day to day process of creating Battle Lines? How did you decide what to cut, and what images needed broad landscape panoramas?

Ari: The collaborative process was both the best and most challenging part of writing Battle Lines. From the first, I relied on Jonathan to help me understand graphic books. And as our work progressed, I began looking to him to teach me how to construct a narrative using strategic silences and well-crafted visual images rather than text. At the same time, Jonathan tells me that he counted on me to provide historical content and also a sense of the state-of-the-art in the scholarly literature, but I think he’s probably just trying to spare my feelings.

As for our work flow, we talked for hours and hours on the phone about how to realize our vision for a chapter. Jonathan then produced a very rough draft, which, typically a few weeks later, he shared with me. After discussing that material—which meant many more hours on the phone—he would work on a second draft. Then, after talking through that material and taking notes for future reference, we typically let the chapter sit while we moved on. And so it went until we had a complete draft of the book, at which time we went back through the full text and discussed what needed to stay, what needed to go, and what we needed to add before we moved to color and the last touches.

Finally, we conducted what amounted to an informal but rather rigorous peer review. I sent a penultimate draft of the book to approximately fifteen scholars around the country, and Jonathan shared the same material with a comparable number of artists and fiction writers. Once we had their feedback, we discussed common themes that emerged across the critiques and revised the book again, adding new material and cutting some pages that didn’t work as well as we had hoped.

Amanda: Jonathan, did you do anything special to research the clothing, military equipment, or other material objects that you depict in your illustrations?

Jonathan: I used this book as an excuse to finally visit some of the battlefields and historic sites like Gettysburg or Harper’s Ferry that I’d only ever read about. And because the book was timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the war, there were all sorts of special events going on. My favorite was probably the reenactment of the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland—there were thousands of soldiers shooting blanks at each other in a field, cannons blaring, horses rearing, and free refills of soda if you bought the souvenir cup. After the battle I hung out with the reenactors and sketched their uniforms and their equipment—some of them are incredibly precise and detailed. Between that, the troves of photographs from the time period, and museum visits, I amassed a huge stack of reference material to work from.

Amanda: You feature recreated newspaper clippings from the time period that open each section. What was it about this form that appealed to you?

Ari and Jonathan: The newspapers did double duty for us. They gave Ari a chance to provide a larger context to each chapter and to introduce aspects of the history that we just couldn’t fit in the graphic narrative. We also recognized early on that the newspapers would function as palate cleansers, almost like taking a deep breath before diving back into the emotional intensity of this story.

Amanda: Tell us a little about your favorite scene in the book.

Jonathan: All of the scenes in this book started out in my head as being my favorite, and the trick was just figuring out how to make them look as cool on the page as they do in my imagination. One of the places where those two versions most closely align is at the end of Chapter 9: Draft Riots, where three different stories converge in a wordless, gut-punch of a climax. Somehow it came out feeling both honest and cinematic. I’ll put that scene on my resume.

Ari: My favorite page in the book is the culmination of the chapter that chronicles the aftermath of Gettysburg. There are so many layers to the story of the photographer, a man named Alexander Gardner, who had his assistants pose a dead body in order to capture one of the iconic—and staged—images of the war.

Amanda: Jonathan, what was the most difficult scene to illustrate and why?

Jonathan: Ari and I had a really hard time with how we should tell the story of the Massachusetts 54th, probably the most famous African-American regiment of the war. They suffered terrible losses in an assault on the Confederates at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, and after the battle, as a sign of disrespect, their bodies were tossed into an unmarked mass grave. This turned out to be an important moment in the history of race in America, but it was really hard to draw in a way that communicated both the vitriol of the Confederate grave diggers and the dignity and heroism of the black soldiers who died in the assault.

Amanda: Ari, what was the most difficult section to write and why?

Ari: I found the process of writing the newspapers incredibly challenging. As a historian, my tendency when trying to answer a question is always to rely on more words. But in this case I needed to relate the history of the war in a series of 200-word articles. I lost a lot of sleep worrying about all of the material that ended up on the cutting-room floor.

opens in a new window

Amanda: While we were editing the book, you both came up with some wild ideas that didn’t make the cut. What were your favorites? Could you describe them?

Jonathan: At one point I was dead-set on doing a chapter about the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which included, among other wonders, the world’s largest butter sculpture. I see now, just in writing the previous sentence, that there’s really no reason why that story needs to be in a book about the Civil War. There are probably other, wilder ideas, but nothing worth admitting out loud.

Ari: One of those ideas that Jonathan thinks isn’t worth admitting was my hare-brained scheme to include a talking statue as the object at the center of one of the chapters. The thing is, there are Civil War memorials scattered around the nation that depict a slave kneeling in gratitude at the feet of a Union soldier. But historians have argued in recent years that slaves actually participated in their own emancipation in a variety of important ways. And so I wanted to have one of those statues—of a standing soldier and a kneeling slave—come to life and discuss the absurdity of its own existence. It was an incredibly terrible idea, and Jonathan was kind enough to tell me so almost every time we talked on the phone.

opens in a new window opens in a new window

Jonathan Fetter-Vorm is an author and illustrator. His Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb was selected by the American Library Association as a Best Graphic Novel for Teens in 2013. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Ari Kelman is the McCabe Greer Professor of the Civil War Era at Penn State University and the author of A River and Its City and A Misplaced Massacre, winner of the Bancroft Prize and the Avery O. Craven Award. He is a regular contributor to The Times Literary Supplement and has written for The Nation, Slate, and The Christian Science Monitor, among other publications. He lives in State College, Pennsylvania, with his wife and two sons.

Amanda Moon is a senior editor at FSG.