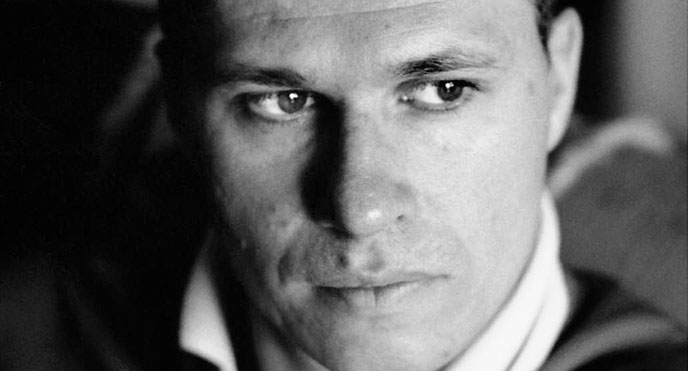

Aleksandar Hemon and Sean McDonald

From the title alone, Aleksandar Hemon’s new novel, The Making of Zombie Wars, suggests that the author is up to something new and different. And while it’s not exactly what you’d call a traditional “zombie novel,” Hemon does admit that it could be described as a “roller-coaster ride of violence and sex.” Here, he talks to his editor, Sean McDonald, about how he changed up his writing process for this book, even enrolling in a screenwriting workshop; why this book maybe isn’t so different from his earlier books; and the challenges of being “funny all the way through.”

And don’t think the funny stops at the end of this conversation—you can track Hemon down for more in person this weekend in Chicago for National Bookstore Day.

opens in a new window |

Sean McDonald: From your piece a few years ago about the making of the movie Cloud Atlas to your recent work on Love Island you’ve fully revealed to the world your deep interest in film. The Making of Zombie Wars takes it even further. How deep does it run?

Aleksandar Hemon: I’ve always loved film. I used to write (bad) film reviews before the war. In the mid nineties, after relocating to Chicago, I saw about 450 movies in one year—and this at the time I was working for minimum wage.

I loved working on Love Island, the movie I wrote with the brilliant Bosnian director Jasmila Žbanić. I could see how that screenwriting mode of storytelling could become obsessive, but I could also identify all the infelicitous insecurities that come with writing for uncertain ends. When you write a story, it exists even if it’s not published. But a script is nothing unless it enters the domain of (possible) production. Even if a script gets produced, it gets erased by the film itself. The script has no lasting substance or value—other than screenwriting students, no one cares to read them. A script never leaves the realm of potentiality. I wanted Joshua to wallow in that field—he obsessively imagines unwriteable scripts which could only result in unproducable movies.

SM: You wrote an early version of this book as a screenplay. Why did you do that? Was the intention always to turn it into a novel?

AH: Sometime in the fall of 2009, I wrote a short story in one sitting. I was avoiding reading student work and, lest I feel guilty for doing nothing, decided to crank out a story that had been on my mind ever since a married ESL student of mine had blatantly hit on me. She was very sexy, but I declined her offer. I was in a relationship with a woman who’d become my first wife—sadly, I strived to be a decent man. But I’d kept imagining what an affair like that would’ve been like. So, in six hours or so, I wrote a story that followed that alternative trajectory. I sent it to The New Yorker where they liked two-thirds of it, but couldn’t get around the ending. I could’ve worked on a different ending, but I realized I didn’t really know what happened after the story (abruptly) ceased. So I wanted to develop a plot beyond the kernel story and for that I decided to write a script. I tend to get embroiled in language, so I figured that writing a script would allow me to establish a sequence of events that would constitute some kind of a plot.

The first drafts of all of my other books I wrote in longhand. That allowed me to slow down the process and address the language, word by word, as it were. But I’ve learned that a method can easily turn out to be a lazy habit, so found it stimulating to do it differently. Thus I wrote the script for The Making of Zombie Wars, minus the last two chapters. There was no Spinoza in it. Also all the Bosnian characters were Russian. This was because I wanted a) not to know how the book would end before I wrote it and b) I wanted to leave some character discovery for the prose-writing phase—I wanted to be with the Bosnians. But I’d cut and paste scenes from the script and enlarge them until they became parts of chapters.

SM: So you enrolled in a screenwriting workshop in Chicago when you were working on the screenplay. What was the class like?

AH: I’d never been in a workshop of any kind (except for those I taught), let alone a screenwriting one. I signed up on a whim, thinking that I’d have to turn something in every week, which would force me to write fast. I had to turn in pages every week. I learned the lingo (“pages,” being “in the room,” etc.), but I also learned to appreciate the freedom of non-professionals. I realized that, as a professional, I actually always considered the feasibility of my literary projects—I calculated what could and should be done, because I had experienced limitations and taken them to be a natural part of the process. But some people in the workshop had no qualms about what could or could not be done or how much it would cost. The possibility of actually making a movie was so remote, and they had no experience of production, that they came up with the most outrageous ideas with no self-editing whatsoever. This was liberating to me. I realized that I had become used to myself and my methods, which were merely comforting habits. And because my fellow workshoppers did not know what exactly I was up to (though I told them I was trying to develop a story by way of writing a script), their comments were refreshingly hard to anticipate. I was willing to continue with the workshop after the initial eight weeks, but life interfered.

SM: The book is punctuated with Josh’s absurd screenplay ideas. Do you have lots more lying around on your hard drive, or can you just produce them on demand?

AH: One aspect of my writerly mind is that I compulsively come up with underdeveloped plots for possible stories. So that I could be watching two people in a coffee shop, and there is a bee flying around them and I imagine a scene in which the bee stings the woman who blames the man for not paying attention to the danger, and then she has a life-threatening allergic reaction and he has to take her to the hospital and so on. I usually discard those ideas, without making any notes. I wanted Joshua to come up obsessively with plots, except he writes down his ideas and reliably fails to develop them. I wrote a lot of script ideas for him, but didn’t include them all. But now I have a format, so I’ve written down a few Joshuaesque script ideas after I finished the book. Each book—indeed each piece—I write alters my mind in some way. It could be that my writing career is but a steady progression toward some kind of dementia.

SM: Joshua is the first protagonist you’ve written who was born in the USA. And the details of his backstory don’t seem to share a whole lot with the life story of one Aleksandar Hemon. Why did you make that choice? Were there any particular challenges, or a special sense of liberation?

AH: Joshua is as “autobiographical” as any of my (main) characters. I taught English as a second language; I was once tempted by a married student; my father was once diagnosed with prostate cancer; I’ve known crazy Marines; I’ve lived in Chicago for most of my adult life; I’ve suffered from writing obsession etc. I did want to write in third person, which I had done before but not for the entire book. One of the advantages of (pre)writing a script for the book was that I could deploy a lot of dialogue and have a lot of characters. The challenge was to have them all speak in different, recognizable voices.

SM: The book is set in a very specific time during the Bush years. Why?

AH: It takes place at the time of the invasion of Iraq. Those days were a heyday of the great American dick fantasy because our superpower was increased by fallacious (or phallacious) self-righteousness. I remember that the majority of Americans were not only high on revenge—killing some Arabs felt good to the hurt national soul—but also on the spectacle of the might deployed. There was a Messianic aspect as well—we were also going to save the world, take the lost Arab tribes to the promised land of capitalism and democracy. And the fact that much of the invasion coincided with Passover was just too tempting for a writer. Joshua’s trajectory—from self-indulgent confusion to total disaster by way of lies—is not unlike Bush’s America.

SM: I’ve always thought your writing is very, very funny and am always eager/desperate for people to notice that. But in The Making of Zombie Wars the humor is working at a different level, it strikes a different tone. What inspired/motivated that? And how do you think it’s different from your other work?

AH: I don’t think that this book is fundamentally different from my other books. It is part of the same continuum—or, rather, a field. But I did want to organize the narrative around humor. I decided early that the funny principle will govern: that is, if in doubt about something, I should err on the funny side. I didn’t want it to be just funny, but I wanted humor to be the main conduit of meaning, the main channel of communication with the readers.

Writing Love Island I learned that comedy is the riskiest of genres. With drama, people may even dislike the film/book at first, but then upon reflection—ten days, six months later—can return to it. With comedy, if it’s not funny right away, nobody is going to laugh in a week.

It became clear to me that if people didn’t find it funny, Love Island was dead on arrival. I sat in the audience, among two thousand people, at the Sarajevo premiere of the movie, thinking that I would die on the spot if they didn’t laugh. They did.

With The Making of Zombie Wars I wanted to go beyond my comfort zone and see if I can sustain the funny all the way through. They challenge was exhilarating, not unlike skiing at a great speed—one mistake could end it all.

Since my first book, The Question of Bruno, I’ve been answering the question “What is your next book about?” by saying “It’s a roller-coaster ride of violence and sex.” I finally lived up to my bullshit. But I did enjoy the roller-coasting in The Making of Zombie Wars. I might do it again, I don’t know where, I don’t know when.

I should also point out that I am terrified of actual roller coasters. I have never taken a ride on one of those. And I never will.

Aleksandar Hemon is the author of The Lazarus Project, which was a finalist for the 2008 National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, and three books of short stories: The Question of Bruno; Nowhere Man, which was also a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; and Love and Obstacles. He was the recipient of a 2003 Guggenheim Fellowship and a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation. The Making of Zombie Wars is his latest novel. He lives in Chicago.

Sean McDonald is the executive editor and director of digital and paperback publishing at FSG, as well as the publisher of FSG Originals.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Sneak Peek: Jonathan Franzen’s Purity

What, Exactly, Have You Been Doing for the Past 14 Years? by Arthur Bradford

Clancy Martin in conversation with Amie Barrodale