Alex Ross, renowned New Yorker music critic and author of the international bestseller and Pulitzer Prize finalist The Rest Is Noise, reveals how Richard Wagner became the proving ground for modern art and politics—an aesthetic war zone where the Western world wrestled with its capacity for beauty and violence. Neither apologia nor condemnation, Wagnerism is a work of passionate discovery, urging us toward a more honest idea of how art acts in the world. In this excerpt, Ross takes us through the writer Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s obsession with Richard Wagner. FSG will be publishing Wagnerism on September 15.

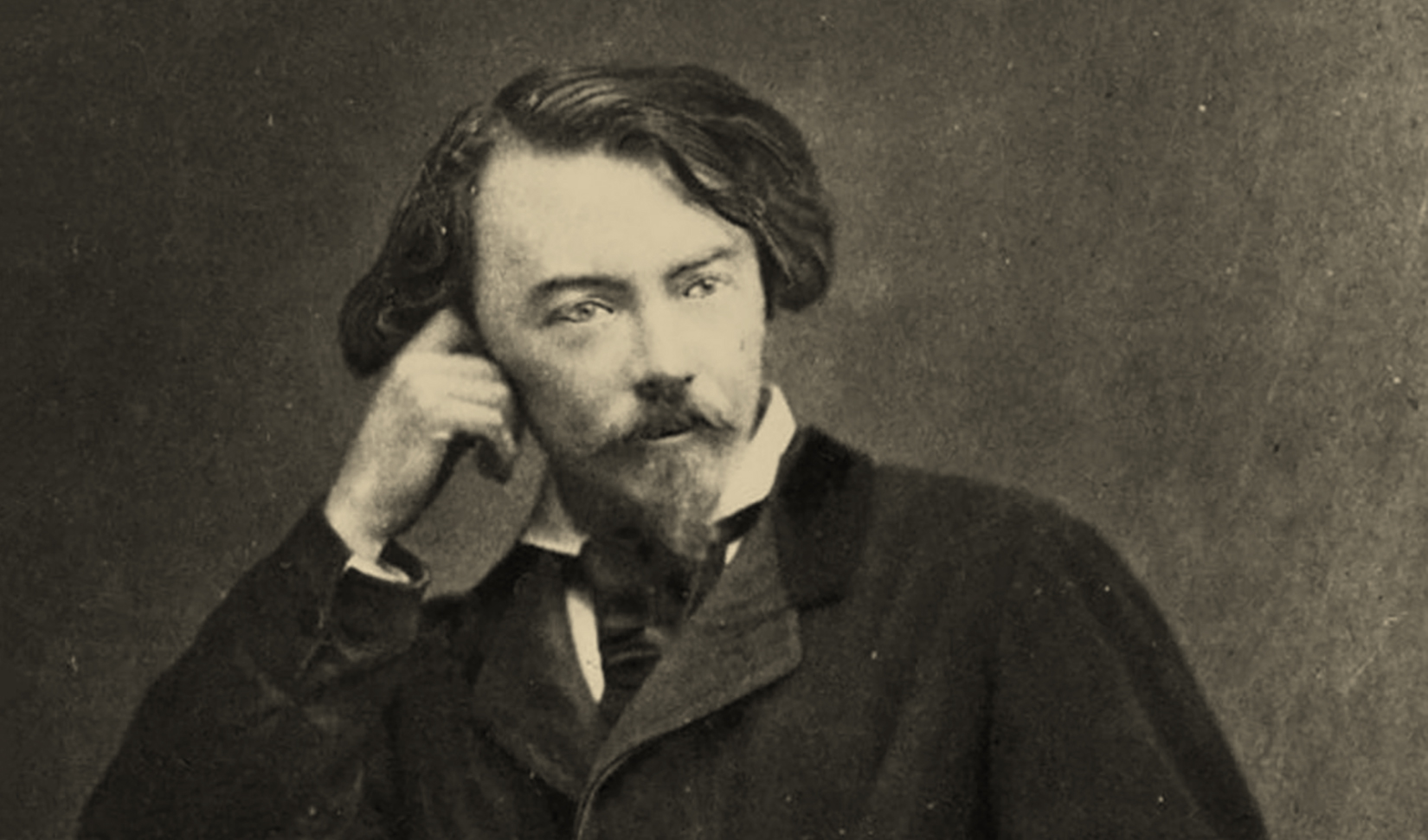

“He always brought in a festival,” Stéphane Mallarmé said. “Time annulled itself those nights.” The Goncourt brothers recalled the “feverish eyes of a victim of hallucinations, the face of an opium addict or a masturbator, and a crazy, mechanical laugh which came and went in his throat.” This absinthe-breathed bohemian was, in fact, the scion of an ancient family, as his page-wide name testifies: Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, Comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. Born on the Brittany coast, Villiers could claim proximity to the romance of Tristan: the hero comes from a Breton line, and, in Wagner’s version, dies in the family castle. One of Villiers’s distant ancestors had been the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta, and family lore held that he left a great treasure buried somewhere. Villiers’s father, Joseph, engaged in ill-advised real-estate ventures in order to carry out excavations in Brittany. According to Villiers’s biographer, Alan Raitt, the only thing Joseph ever found was a dinner service. His son inherited the fixation on lost glory, transmuting it into literary fantasy. Auguste gained early notoriety for having declared his candidature—seriously or not, no one could be sure—for the throne of Greece.

Villiers’s poems, plays, novels, and tales elude the usual literary categories. How to classify The Future Eve, a kind of baroque science-fiction novel in which Thomas Alva Edison invents a female android? This author is most approachable, though not necessarily most likable, when he is engaging in vicious satire: his collections Cruel Tales and Tribulat Bonhomet rail against bourgeois fatuity and callousness. In one story, the insufferable Dr. Bonhomet breaks the necks of swans, because he has heard that the birds sing most beautifully when they die. Villiers suffered from the usual failings of male European writers of the period: antisemitism, misogyny, elitism. William Butler Yeats liked to quote a characteristic line from Villiers’s mystical drama Axël: “As for living, our servants will do that for us.”

William Butler Yeats liked to quote a characteristic line from Villiers’s mystical drama Axël: “As for living, our servants will do that for us.”

Music-mad from youth onward, Villiers was an energetic if eccentric pianist who, like Nietzsche, specialized in improvisations. He met Baudelaire a year or two before the Tannhäuser scandal, and a shared regard for Wagner cemented their friendship. “I will play Tannhäuser for you once I am settled in your neighborhood,” Villiers wrote. He also fell in with Catulle Mendès, a handsome poet and novelist who floated through Paris society beneath waves of Lisztian hair. The son of a Sephardic Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Mendès won early fame—and a brief prison term—by publishing mildly erotic poetry in his Revue fantaisiste. That short-lived journal, founded in 1861, was an early organ of the Parnassian movement, which valued formal poise and exquisite precision in the Gautier manner. In 1866, Mendès married Judith Gautier, Théophile’s daughter, who was on the verge of her own significant literary and artistic career; the two had met at one of Pasdeloup’s concerts.

In 1869, the Mendès couple, having proved their worth as combative Wagnéristes, received an invitation to visit the composer in Tribschen. Villiers joined them on the pilgrimage. The itinerary also included Munich, where rehearsals for the premiere of Rheingold were under way. Beforehand, Villiers had written a story titled “Azraël,” which he dedicated to Wagner, “prince of profound music.” Oddly, it was on an Old Testament Jewish theme, depicting King Solomon in conversation with the Angel of Death. As the party approached Tribschen, Villiers displayed mounting elation. He gave Wagner the obscure nickname “palmiped of Lucerne,” and exclaimed, “He is cubic!”

The palmiped met them on the railway platform, wearing a large straw hat, which made him look like Wotan. Gautier remembered being fixed for a full, silent minute by the soul-scoping intensity of his gaze. In letters home, Villiers described the “fabulous being” in terms suitable for the cruel angels and crazed scientists of his stories: “Something like immortality made visible, the other world rendered transparent, creative power pushed to a fantastic point, and, with that, the sweat and the shining of genius, the impression of the infinite around his head and in the naïve profundity of his eyes. He is terrifying.” He is “the very man of whom we have dreamed; he is a genius such as appears upon the earth once every thousand years.”

He is “the very man of whom we have dreamed; he is a genius such as appears upon the earth once every thousand years.”

Cosmic ramifications notwithstanding, Wagner acted much of the time like a hyperactive child. Mendès has him throwing his hat in the air, dancing about, gesturing with nervous excitement, and talking without pause. One day, he made a catlike jump from an upper story of the house into the garden. When Villiers was later asked whether the composer was a pleasant conversationalist, he replied, “Do you imagine, sir, that the conversation of Mount Etna is pleasant?” Like Nietzsche and Baudelaire, Villiers experienced Wagner as a human volcano.

The next year, Villiers, Mendès, and Gautier set out on a second Wagner vacation, witnessing the premiere of Walküre in Munich and paying another visit to Tribschen. This time, the Franco-Prussian War intervened. Otto von Bismarck had manipulated a diplomatic dispute into a major crisis, and Napoleon III declared war on July 19, just as the French party—now including the composers Camille Saint-Saëns and Henri Duparc—alighted in Lucerne. Despite the news, the company sat enthralled as Wagner and Hans Richter performed excerpts from the Ring. “It is the Nibelungen, all the night of time,” Villiers wrote. The Nietzsche siblings, Friedrich and Elisabeth, also dropped by, making for a singular constellation of personalities. The French had hoped to stay for Richard and Cosima’s wedding, but this was delayed for legal reasons, and tensions were simmering. “R. demands of our friends that they understand how much we hate the French character,” Cosima noted. The Wagners became exasperated by Villiers’s “bombastic style and theatrical presentation”—a severe reprimand in this household. Russ, the chief family dog, bit Villiers’s hand. On July 30, the French departed, announcing their intention to visit a “friend in Avignon,” who turned out to be Stéphane Mallarmé.

Villiers never made it to Bayreuth for the Ring. Reportedly, he broke down in tears when he realized that he couldn’t afford to go. His Wagnermania persisted, reaching its apex in Axël, which once loomed over fin-de-siècle literature as a successor to Faust. In 1931, the American critic Edmund Wilson honored Villiers’s fading fame by giving the title Axel’s Castle to his history of Symbolist and modernist literature. The play first took shape at the time of Villiers’s visits to the Wagners, for whom he may have read aloud an early draft. The euphoric demise of its self-annihilating lovers, Axel d’Auersperg and Sara de Maupers, smacks of Tristan und Isolde; its story of fatally alluring gold, meanwhile, recalls the monetary curse of the Ring, not to mention the treasure-hunting escapades of Villiers’s father. Villiers was still revising and expanding the play when he died, in 1889. It reached the stage only in 1894, in a performance that lasted nearly five hours, about as long as Tristan itself. “Seldom has utmost pessimism found a more magnificent expression,” said Yeats, who was present for the occasion.

The climax of the play is like Tristan and Götterdämmerung superimposed. Sara, having fled a convent, arrives in Axel’s castle in the Black Forest, led there by a mysterious book. Axel briefly engages her in combat, gazes upon her, and falls in love. He comes to resemble not only Tristan and Siegfried but also Wotan with Brünnhilde (“I will close your eyes of paradise”) and Siegmund with Sieglinde (“Sara, my virginal mistress, my eternal sister”). What to do with the sudden onset of passion? Sara wants to flee to a remote locale and “listen to the hummingbirds in some hut in the Floridas.” Axel is unconvinced: “Oh! the external world! Let us not be dupes of that old slave.” To break the veil of illusion, he says, they should kill themselves at once. After a certain amount of hesitation, Sara agrees. As the humble songs of a village marriage are heard from outside, she draws poison from the ring on her finger. Axel expresses the hope that the rest of the human race will follow suit. After the lovers die, though, the stage directions dictate a different outcome: “Disturbing the silence of the terrible place where two human beings have just dedicated their souls to the exile of Heaven—we hear from outside the distant murmurs of the wind in the vastness of the forests, the vibrations of awakening space, the swell of the plains, the hum of life.” The forest murmurs on; the world has not committed suicide at Axel’s behest. The ironist in Villiers shows the limits of his characters’ transcendent longing.

No one possessed in the same degree the power to heighten farce and make it shoot bewildered into the beyond; he always had a punch-bowl flaming in his brain.”

Lost to history are Villiers’s fabled one-man Wagner entertainments. Joris-Karl Huysmans left a memorable description: “After the meal, he sat down at the piano and, lost, out of this world, sang, in his feeble, cracked voice, several pieces by Wagner, among which he interpolated barracks choruses, joining it all together with strident laughter, crazed nonsense, and strange verses. No one possessed in the same degree the power to heighten farce and make it shoot bewildered into the beyond; he always had a punch-bowl flaming in his brain.”

Alex Ross has been the music critic for The New Yorker since 1996. His first book, the international bestseller The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and won a National Book Critics Circle Award. His second book, the essay collection Listen to This, received an ASCAP Deems Taylor Award. He was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2008 and a Guggenheim Fellow in 2015.