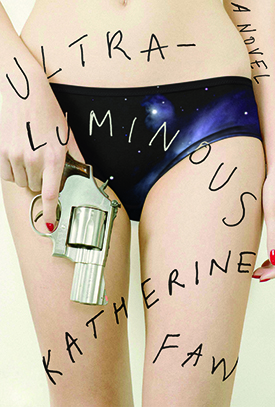

Katherine Faw’s dark new novel Ultraluminous takes us into the life of K, a high-end, girlfriend-experience prostitute whose routine includes everything from Duane Reade sushi to gallery shows to heroin. The New Yorker called the book “a damning, often hilarious account of toxic masculinity and Wall Street money culture.” At a gathering to celebrate Ultraluminous, Faw joined Elle’s Estelle Tang, journalist and editor Meredith Talusan, and artist Erica Prince to discuss topics ranging from violence against women to gender performance in fashion to the complex relationship between beauty and power.

ON BEAUTY AND POWER

Estelle Tang:

Ultraluminous had me thinking a lot about beauty. The main character is an extremely beautiful woman, and we can’t see her, but her power is very obvious. I was thinking of a turning point in my life when I realized what kinds of power beauty could have, and I realized that despite whatever beauty standards I had absorbed, in terms of thinking that beauty was a good—a good with no bad—that it could have a power that wasn’t always going to be so positive. What has your relationship to beauty been in your life? Was there something in Ultraluminous that you wanted to explore in terms of the concept of beauty and how it affects other people?

Katherine Faw: Yeah, well, I wanted K—she’s a prostitute, and a very high-class girlfriend experience prostitute—I wanted her to be able to command a lot of money and to be able to date these very high-level Wall Street guys, so I figured her beauty would be very apparent, and she’d be a shiny, sparkly thing for these men to show off. She’s ultra-luminous, part of the meaning of the title. As far as beauty in my own life, I mean, I’ve always loved beautiful women for as long as I can remember. As a little girl I was so attracted to fashion models and really stylish women. When someone is that beautiful, it can be isolating, like when you’re a supermodel. Not only men, but also women can isolate you, where you feel very alone, and I think that is how K feels in the book. She’s always been this isolated figure for people to project onto.

Tang: Meredith, you took a year off from using makeup, and I’m curious about what happened in that year.

Meredith Talusan: Well, I’ve had a very complicated relationship to gender. I’m trans, and I grew up in a rural hamlet of the Philippines, where I don’t even remember having a mirror, really—when I was six or seven was my first memory of looking at a mirror. So there’s a way in which my entire identity was formed outside of this notion that I had to be beautiful, especially because I was growing up as a boy. There was this really weird way in which, as soon as I started wearing makeup and transitioning—at the time I was 115 pounds, 5’6”, very thin, blond, all of these qualities that are like, Oh, this is a very niche twink gay man—all of a sudden, it just flipped. It was really funny because people suddenly gave me discounts at clothing stores, or allowed me to return things when it was clearly opened and tampered with. There was a period of time when I was really like, this is a power that I’ve discovered and I’m gonna start using, and I feel like over time it became clear that there’s a cost. There’s a lot of pressure to maintain a certain kind of image of yourself for other people, and I feel like not wearing makeup for a year was a way to hit a reset button and then kind of reclaim aestheticism and dressing for myself. Now, for instance, I felt like wearing shiny silver lipstick tonight, and I knew that guys would just be like Ehhh. It’s not like, ruby red. And now, I don’t give a shit what you think, and that’s sort of been my movement away. I just started wearing makeup for myself and to fuck up other people’s perceptions.

I feel like not wearing makeup for a year was a way to hit a reset button and then kind of reclaim aestheticism and dressing for myself.

I really relate to this idea of makeup as tool, I think in part because I was just not socialized to care about whether or not I was beautiful. I was socialized to care whether or not I was smart. So if my intelligence feels threatened, that’s when my claws come out. And it’s weird to live my life that way, in a world that perceives me as female, because there are so many assumptions that attend to that. People see this on my Instagram or what have you—I’ll have this really weird expression, or I’ll have hairs on my chin, or I’ll have a split lip and it doesn’t matter to me. Part of the reason why I want it not to matter is because I feel that the world is constantly trying to tell me that it should, and I play with that perception for the purposes of my life—especially as somebody who lives in public spaces, I know that there are certain expectations of me. If I get full makeup done and I post a selfie on Instagram, it’ll get hundreds more likes than other things that I post, but at the same time, it’s really important to me that the performance doesn’t bleed into my own perceptions of how I should be as a person.

ON ART AND SELF-IMAGE

Erica Prince: My transformational makeover project is something that’s been ongoing since 2014. It’s relational, it’s not performative, and I think there’s a really distinct difference there because I’m not pretending to be someone else, I’m just meeting with people really intimately and transforming their physicality. I’m a multidisciplinary artist, so I work in sculpture and drawing. I always thought I was a really quiet object-maker until I realized that this thing I was doing on the side—giving my friends makeovers—was actually really powerfully affecting their psychology. It was this tool that I had that allowed me to interface with people and show them a different side of themselves that they didn’t have an opportunity to explore. I loved makeup, and I loved playing dress-up, so that was something I wanted to facilitate for them.

Before the makeover I give people a survey that’s intended to provide a moment of introspection and reveal aspects of a person that I might take into consideration in their makeover. It often reveals how well they know themselves, or what they might feel comfortable with or not comfortable with. In the makeover scenario, there’s also a post-makeover survey that becomes a moment of reflection after the people are transformed. And I should say also that the makeovers that I do are not actually about beauty; they’re about turning people into someone besides themselves in an effort to gain perspective on who they are every day. So it’s not like the typical makeover strategy where it’s like, Become a more beautiful version of yourself, it’s actually just like, Become something else.

the makeovers that I do are not actually about beauty; they’re about turning people into someone besides themselves in an effort to gain perspective on who they are every day.

Tang: There’s a great video, actually that shows a little bit of what this process is like. When the subject looks at herself in the mirror—I guess they don’t get to see what Erica’s doing at the time, because she just lets out this huge bark of laughter. What are the kinds of things that people say when you change what they look like?

Prince: That’s my favorite part of the whole process. Oftentimes I take full control and they relinquish all responsibility and I surprise them, and when I turn them around and show them themselves, they don’t recognize themselves at all. I try to take people to an extreme so that they completely don’t know who they’re looking at in the mirror, and there’s a range of reactions. Either they flip out and can’t make eye contact with themselves because they’re so uncomfortable, or they start laughing hysterically, or they’re just totally shocked, or they immediately start acting completely different. It’s really interesting to watch how they suddenly feel like they have permission to do things that they wouldn’t have done when they walked into the salon as themselves.

ON GENDER

Tang: Meredith, I’m curious about your work at them., which is an LGBTQ media platform that quite recently started. You have amazing photo shoots—people of all genders, people wearing things that are not “for their gender,” and makeup used in a very beautiful but not traditional way. I’m wondering about the conversations that you’re having internally about standards of beauty and what you would like to do in terms of representing them.

Talusan: As a publication, we are gender-neutral across the board, so when we have an accessory or when we have an item of clothing for a shoot, whatever it is, it’s just as likely for a male-bodied person to wear it as a female-bodied person. For us, it’s about clothes and makeup and everything you wear, it’s about expression, it’s about how you want to present yourself to the world, not how the world wants you to be. I think that that’s a really core aspect of queer identity—moving out of the way of what this entire cis-heteronormative world wants you to be—but at the same time, that world also makes products and clothes and makeup, not necessarily with you specifically in mind. So one of the best ways to deal with that is just to remix and to use clothes and accessories in ways that they weren’t intended, and that’s something we consistently do, and that I’m really proud of.

ON USING ART TO RESPOND TO HOW WOMEN ARE TREATED

I wanted to think about what it would be like for her as a sex worker, and the fact that you are in danger often, mortal danger, because you have no idea what’s going to happen when you’re alone with this man who you know nothing about.

Faw: K was a hard character to write about. As far as the violence goes, I wanted to think about what it would be like for her as a sex worker, and the fact that you are in danger often, mortal danger, because you have no idea what’s going to happen when you’re alone with this man who you know nothing about. Except that he’s willing to pay this fee, so he says. Also, she’s been a prostitute since she was eighteen, over fifteen years—so I thought there was no way she could’ve gotten by unscathed. And violence against women happens whether you’re a prostitute or not, and I think she’s also numb to it and she accepts this kind of escalating violence with one of the clients as just kind of the price of being with him, and she feels like she is controlling the situation even though she’s really not. I mean, it wasn’t harder to write than anything else in the book. I just wanted it to be true to what I imagined her life would be like.

Tang: Erica, I wanted to ask: what it is like, in a political moment that is very violent towards women, and political engagement feels like such an important thing to do, being an artist who works with other people? Right now art feels like something that’s, I suppose, life-giving. I’m curious about whether you’re drawing any more or a different kind of emotion from being an artist at this point in time.

Prince: I think in light of what’s happening in the world right now, all artists are sort of stopping to re-evaluate, trying to figure out how their work is relevant in the world, given the heaviness of what’s happening around us. I guess in my work, I try to really connect with people on a personal level and cultivate that intimacy with them. With the makeovers, in particular, I wanted to develop a project that was really generous. A lot was happening in the art world that felt like people finding a captive audience and holding them hostage to do something really selfish. So I wanted to flip that on its head and be like, I’m offering this service, and it’s actually about you—it’s not even really about me. [laughs] And in that, I’ve met some incredible people and I have these really amazing conversations because I’m so close to someone, touching their face for a good amount of time, and I’ve probably never met them before, but because we’re having this moment. They tell me stories and I feel like we’re connecting, and it’s incredible to watch—I mean, hopefully, if the makeover goes well, they tap into a side of themselves that they hadn’t discovered before. I’ve had a lot of people come back to me and tell me how the processing of their new identity happened slowly after they left the salon. So I love it when people leave a little bit flustered and confused and disoriented—that means it was a good makeover. I guess I’m trying to empower people in a very indirect way, especially women—my audience is primarily female, though it’s not all female. And there’s this sense of community that happens when people get together and play dress-up or experiment with their physicality. It’s sort of like the thing teenage girls do at slumber parties—they’re like, maybe I’m this person, or maybe I’m that person, and you’re like, oh, that’s so you. There’s a dialogue that happens that I think is really interesting and empowering. I’m trying to make work that has people’s day to day lives in mind, and makes them ask questions that feel relevant and important, as opposed to just plopping something into the world that is all about me and being like, here, you should have this.

Katherine Faw’s debut novel, Young God, was long-listed for the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize and named a best book of the year by The Times Literary Supplement, The Houston Chronicle, BuzzFeed, and more. Her second novel is Ultraluminous. Formerly known as Katherine Faw Morris, she was born in North Carolina, and lives in Brooklyn.

Estelle Tang is the culture editor at ELLE. Previously, she was a children’s scout at KF Literary Scouting, NYC. She has published writing in The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Hairpin, Jezebel, Salon, The Toast, Pitchfork, Rookie and more. She lives in Brooklyn.

Meredith Talusan is an award-winning journalist and author, who’s also senior editor for them. They have written features, essays, and opinion pieces for many publications, including The Guardian, The Atlantic, VICE, The Nation, Mic, and The American Prospect. They received the 2017 GLAAD Media and Deadline awards and contributed to several books, including Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance, and Revolution in Trump’s America. They live in New York City.

Erica Prince is a multidisciplinary artist whose work presents opportunities for speculation and exploration of potentialities within lifestyle design. In addition to her ongoing relational project, the transformational makeover salon, she also makes functional ceramic sculptures, drawings, and large-scale installation. She lives in Brooklyn.