Ted Fullilove, aka Mr. Peanut, is not like other Ivy League grads. He shares an apartment with Goldberg, his beloved battery-operated fish, sleeps on a bed littered with yellow legal pads penned with what he hopes will be the next great American novel, and spends the waning malaise-filled days of the Carter administration at Yankee Stadium, waxing poetic while slinging peanuts to pay the rent.

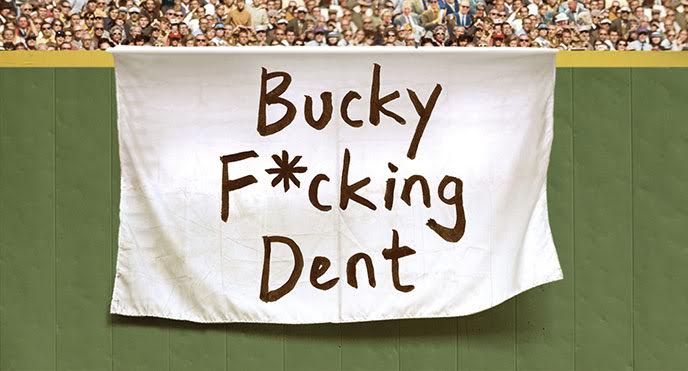

This is Bucky F*cking Dent, David Duchovny’s new novel, a richly drawn story of the bond between fathers and sons, of Yankee fans and the Fenway faithful, that grapples with the urgent need to find our story in an age of irony and artifice.

opens in a new window |

You could start cheering during the last line—Jose, does that star-spangled ba-an-ner yet wa-ave. O’er the la-and of the freeeeeeeeee … But not before. Before was disrespectful. It was a fine line that everyone, 60,000 people when Boston was in town, just knew intuitively. Like don’t stare at other people in an elevator, look at the numbers flashing. No eye contact. The intuitive rules of the world that were a mystery only to retards, psycho killers, and children.

The old joke is that the last words of the national anthem are “play ball!” An oldie, but a goodie. The impossible-to-sing “song” came to an end, and the noise of the crowd swelled like it was one happily anxious beast. The game was about to begin, and it was Africa-hot up here in the cheap seats, the blue seats. It was 80 percent Latino in Ted’s peanut dominion, 55 percent Puerto Rican, 25 percent Dominican, and about 20 percent other. The other were mostly Irish and Italian. All his people. It was easy to think of these as the “cheap seats,” and, for sure, they were so far removed from the field of play that there was a discernible lag between the sight of a ball being hit and the crack of the bat. Like a badly dubbed Japanese film. But rather than removed, Ted liked to think of the vantage point as Olympian, that they were all gods on high watching the ant-sized humans play their silly games. So this is where he worked. Yankee Stadium throwing peanuts to mostly men who thought it was funny to call him “Jose” like the first words of the Spanglish version of the national anthem, or Mr. Peanut. Some even called him Ted.

He would rather not to be called Ted. Though he liked his job and it paid the bills, kinda, while he wrote, he was a little ashamed that a man his age, with his education, New York private school, Ivy League, had to throw legumes at people to make ends meet. Yet he actually preferred a job like this that was so far away from what he “should” be doing, falling so spectacularly short of any expectation, that people might think he was doing it ’cause he was a “character,” or ’cause he loved it, or that he was one of those genius, irreverent motherfuckers who thumbed his nose at the world and just generally didn’t give a shit. Rather than be thought of as a failure, which is how he thought of himself, he liked to be thought of as an eccentric. That quirky dude with a BA in English literature from Columbia who works as a peanut vendor in Yankee Stadium while he slaves away on the great American novel. He is so counterculture. He is so down with the workers and the proles. I love that guy. Wallace Stevens selling insurance. Nathaniel Hawthorne punching the clock at the customs house. Jack London among the great unwashed with a handful of nuts in his hand.

Even so, he took pride in his accuracy. He was not a good athlete, as his father used to remind him daily growing up. He threw “like a girl,” the old man said. And it was true, he did not have Reggie Jackson’s arm, or even Mickey Rivers’s chicken wing. If Ted was gonna get a candy bar named after him, it would probably be the Chunky. But over the years, he had honed his awkward throwing motion into a slapstick cannon of admirable accuracy. Even though he looked like he was doing a combo of waving goodbye and slapping frantically at a mosquito, he could consistently hit a raised hand from twenty rows away. The fans loved his uniquely ugly expertise and loved to give him a tough target and celebrate when he nailed it. He could go behind the back. He could go through the legs. His co-worker, Mungo, he of the Coke-bottle lenses and bowling forearm guard, who broke five feet only because of the orthopedic four-inch rubber heel on his left club foot black shoe, sold the not-always-so-cold beer in Ted’s section, and would always keep fantasy stats on Ted’s delivery percentage: 63 attempts, 40 hits, 57 within 3 feet. That kind of stuff. Like batting average, slugging percentage, and ERA for vendors.

Catfish Hunter was pitching today. Ted dug that name. Baseball had a rich tradition of ready-made awesome monikers. Van Lingle Mungo. Baby Doll Jacobson. Heinie Manush. Chief Bender. Enos Slaughter. Satchel Paige. Urban Shocker. Mickey Mantle. Art Shamsky. Piano Legs Hickman. Minnie Minoso. Cupid Childs. Willie Mays. Like a history of the United States told only through names, a true American arithmoi, a Book of Numbers. It was a strange year, though, because the Boston Red Sox, longtime Yankee rivals, but in effect more like a tragicomic foil to the reigning kings, the Washington Generals to the Yankees’ Harlem Globetrotters, were having a great year and looking like they would finally break the curse of the Babe. The Sox had traded Babe Ruth, already the best player in the game, in 1918 to the Yankees for cash. The owner of the Sox, Harry Frazee, wanted to bankroll a musical or something. Was it No, No, Nanette? Ruth went on to become an American hero, a hard-living, hot-dog-inhaling Paul Bunyan in pinstripes who led the Yankees to many a pennant and World Series victory, whose success had conjured Yankee Stadium out of the barren hinterlands of the Bronx: The House That Ruth Built in 1923, where Ted stood today. And the Sox had not won since. Not one pennant. Sixty years of futility looking up in the standings at the hairy ass of the Yankees.

It was mid-June, but already hotter than July. The peanuts did fly, the beer did flow, and the Catfish did hurl. During the few lulls in the game when people were not calling for him, Ted would usually grab the dull sawed-off pencil from behind his right ear and jot down stray thoughts. To be filed later. Alphabetically, of course. Thoughts for the novel he was presently working on, or the next one, or the one that he had all but given up on last year. Writing was not the problem, finishing was. Works in progress with titles like “Mr. Ne’er-Do-Well” (536 pages), “Wherever There Are Two” (660 pages of an outline), “Death by Now” (1,171 pages weighing over 12 pounds), or “Miss Subways” (402 pages and counting). All that would never see the light of day outside of Ted’s Bronx one-bedroom walk-up tenement apartment. Maybe today he would stumble upon a thought that would unleash the true word horde, that would unlock a puzzle, that would unblock him from himself, from his inability to compete and complete.

He remembered Coleridge, in the Vale of Chamouni, had written, “Hast thou a charm to stay the morning-star…?” And that seemed to him the truest, saddest line in all of literature. Can you, man, find the poetry to keep the sun from rising, like a mountain, blocking its inevitable ascent for a few more moments? Can you, who call yourself a writer, find the words that will have an actual influence on the real and natural world? Magic passwords—shazzam, open sesame, scoddy waddy doo dah—warriors lurking in the Trojan horse of words. The implicit answer to Coleridge’s question was: Hell, no. If the answer were yes, he would never have asked the question. The writer will never make something happen in the world. In fact, the act of writing may be in itself the final admission that one is powerless in reality. Shit, that would surely suck.

Ted was thinking about his own powerlessness and ol’ S. T. Coleridge, that opium-toking, Xanadu-loving, Alps-hiking freakazoid, as he sat scribbling on a paper bag some names that might work as magic charms to make time or a woman stay, to spark a story, to make him the man he wanted to be—Napoleon Lajoie Vida Blue Thurman Munson Open Sesame …

The game passed by in its own sweet timelessness, and then it was over. Boston 5, New York 3. Another Yankee loss in this strange-feeling year.

David Duchovny is a television, stage, and screen actor, as well as a screenwriter and director.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

An excerpt of Holy Cow, Duchovny’s first novel

Jeff VanderMeer: Area X Debrief

Catherine Lacey Rewrites Etgar Keret