I begin with a character. As you know, there are many kinds of characters—Henry James’s peripheral but all the same essential character who observes the narrative with the same mystification and curiosity as does the reader; Joan Didion’s ironical and vaguely menacing character, sometimes even the writer Joan Didion herself, who tells you the plot in the first paragraph, and then fills in the blanks; Stendhal’s historical figure, who is a creature both of his own ambition and the strivings of history. The character with whom I begin is a solitary figure, and always a woman (at least so far). But what is it that I am to do with her? Better still, what is it that she will do? If I trust her, she will tell me. Studying her with careful attention, while all the time giving her an inordinate freedom, she will reveal herself to me. How she looks and speaks and thinks; what she is wearing when she is sleeping in the room that I have made for her. There is in her story a certain inevitability, which often surprises and confounds me.

opens in a new window |

My book In the Cut arrived by way of Raymond Chandler and Sherlock Holmes. While I was writing the last Hawaiian novel, I read every mystery and thriller I could find—books about detectives in Bombay and judges in Stockholm, as well as the American classics of the first half of the twentieth century that came to be known as Noir. I wanted to take the traditional American crime story, and to turn it upside down. I wanted my crime fighter, my dissolute, tired, cynical detective who is typical of the genre, to be a woman. And I wanted my female character to survive at the end of the book. As it turned out, the detective in In the Cut is not a woman, and the heroine does not survive, but I did not know that then. I understood that in order to write the book, I would have to do research, something I had never done before in writing fiction. My imagination is vivid, but I would need facts. I would even need impressions. While it is possible to do absolutely anything with the novel—it is one of its charms (and terrors)—the one thing that I did not want to do was to propagandize either for a cause or a point of view. It was in my interest (it is always in the interest of a writer) to be without an opinion at all—a position that later was to cause me to disappoint some critics and readers. But the writer’s work is to render the world, not to alter it. I never intended when I began writing, nor in truth throughout the long two years it took me to finish the book, that In the Cut would be narrated by a dead woman. When I came to write the end of the book, there was no other possible resolution than her horrible death; and once I accepted this, I was bereft. I tried later, when writing the second and third drafts, to change the book so that the story is told by Franny as she is dying, when she would at last understand what had happened to her, but it would not do. In this kind of detective story, the heroine must be as innocent of the (fictional) facts as is the reader, until the end, when all that is mysterious and inexplicable is made clear.

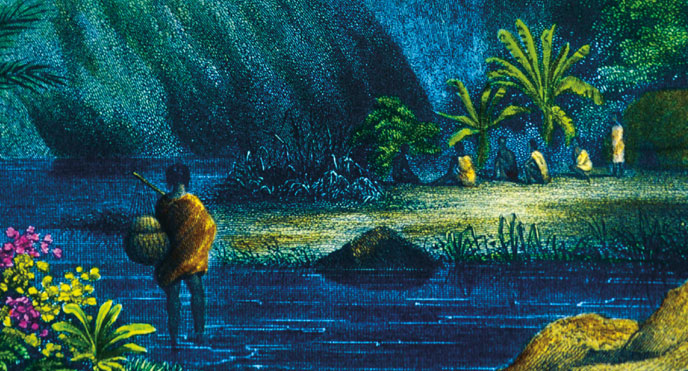

When I began to write my new book, Paradise of the Pacific, which was published this month, I again began with a heroine, the brilliant, cunning, and willful Kaʻahumanu. At first I did not know what to do with her. Her story has been told many times. As I was not writing a novel, I was not able to invent her, or even to imagine her. I did not want to write a book in which I attributed words and thoughts to the characters, or even to attach adjectives to nouns: “Kaʻahumanu, bored and irritable inside the airless and dark grass house in which she was ritually confined during her menstrual period, wondered restlessly if the high surf (she could hear the waves breaking on Kauhola Point at the bottom of the king’s large compound) would continue through the week, when she would be at last cleansed of her defilement.” Many writers do assume the point of view of historical characters, but I dislike it when they do, and tend to put away their books.

In order to find Kaʻahumanu and to keep a clear head, without censure or adulation, I began to read. I did not stop reading for two years. In the end, I had thousands of pages of notes, collected from journals, memoirs, newspapers, gossip sheets, histories, songs, research papers, archaeological surveys, monographs, oral histories, church records. I knew that I was ready to stop reading, which is always difficult for me, and to begin writing, which is even more difficult, when I began to dream of Kaʻahumanu.

As I wrote the new book, my love affair with the great queen, as love affairs tend to do over time, began to include other people—Kamehameha, Lucy Thurston, Liholiho, Dr. Judd, Kauikeaouli, Hiram Bingham, Kaumualiʻi of Kauaʻi, and George Vancouver, among many others—and, to my relief, the numerous characters began to insist on having their own way. This happens, of course, in writing history, as one is expected, if not required to adhere to the facts, but I was interested to discover that in all that is available to the writer of history, certain events, certain statements, certain actions force themselves to the front, insisting upon precedence and illumination, and requiring not only your attention, but your use of them. Given Kaʻahumanu’s guile, I should not have been surprised.

This post originally appeared on Susanna Moore’s terrific blog about the writing of Paradise of the Pacific.

Susanna Moore is the author of the novels The Life of Objects, The Big Girls, One Last Look, In the Cut, Sleeping Beauties, The Whiteness of Bones, and My Old Sweetheart, and two books of nonfiction, Light Years: A Girlhood in Hawai’i and I Myself Have Seen It: The Myth of Hawai’i. She is from Hawaii.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Naomi J. Williams’s on her Writing Routine. Or lack thereof.

Stephen Jarvis on Dickens, Brick Collectors, and Unusual Leisure

The Supernatural Grace of Flannery O’Connor